Howl of the Day: Feb 16, 2016

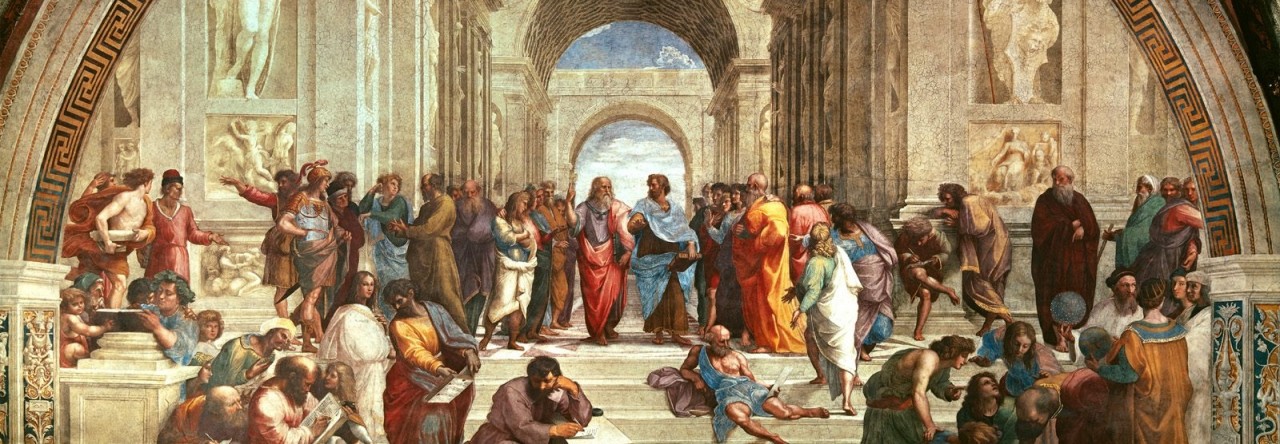

The Second Letter attributed to the philosopher, Plato, contains the famous suggestion that his dialogues present a Socrates made “young and beautiful”. Some people, it seems, concerned with the state of education of children in America, would go a few steps further than Plato did in this sense. They would raise a generation or more of little Socrateses, all not just young and beautiful, but tiny and cute.

Over at the Washington Post’s Answer Sheet, by Valerie Strauss, there is a repost of an article by blogger, Steve Neumann, about the need for philosophy in children’s education.

Strauss introduces the matter by reminding us that President Obama has recently pledged to ask the US Congress for another several billion dollars to bring computer science to more students. She then introduces Neumann as someone with a different view of how education can be improved, and as someone who “says he is interested in doing for philosophy what science journalists do for science”.

Neumann really does want to make little Socrateses. As he warns at the end of his piece: “If we fail to turn second-graders into Socrates, our kids may end up becoming expert at making a living, but they will be incompetent at creating a civil society.” A dire warning, indeed. But is philosophy really good at creating a civil society? Was Socrates a good citizen of Athens? Would he have made a good American?

Socrates devoted his mature life to the discussion of virtue, and he frequently declared justice as the central theme in his inquiries (although he seldom if ever indicated what justice actually consists in). When he gave an account of the philosophic way of life, it included talking about the gods as its highest goal. None of this makes for easy accommodation into the education of our children, or into any formal education for that matter.

Neumann passes over these difficulties by narrowing his view of philosophy considerably:

“When people hear the word “philosophy” they might think first of something like a set of guiding principles or a general worldview. The New England Patriots’ Bill Belichick may have a coaching philosophy, for instance, while someone like the rapper Drake encourages us to have a YOLO attitude toward life. But academic philosophy is that discipline of the humanities concerned with clarifying and analyzing concepts and arguments relating to the big questions of life.”

His aim is to distinguish philosophy proper from the popular misuse of the term. But is something not lost in this abstraction?

The plurality of “philosophies” that are espoused by such folks as Drake and Bill Belichik have no substantive relation to philosophy as such, not least because they exist in a plurality. But insofar as they are a “set of guiding principles” or a “general worldview”, they bear more resemblance to Socratic philosophy than what Neumann calls by that name. It is no small task to make Drake look closer to Socrates than a philosophy professor, but that is exactly what Neumann does by shrinking the scope of philosophy down to an academic discipline.

Teaching children to clarify and analyze important concepts is an excellent idea. Schools can and should do more to give students practice in critical thinking and exposure to serious issues.

And it should go without saying that the manner in which this would be done should include some discussion of philosophy and other organizing ideas. But seeking to make Socrates tiny and cute would be a terrible thing, for philosophy and for our children. By calling philosophy down from the heavens to the 2nd grade classrooms, we risk reducing it to a set of critical thinking skills that, while excellent, will not provide the moral content necessary to make good citizens. Even more importantly, by perpetuating the misidentification of these skills with philosophy, we invite the danger of closing our children off to any eventual interest they might develop in living the examined life.

Important points, lucidly made. But I’m not against introducing philosophy or Socrates to 2nd graders. Children need to learn to question authority and convention, although they also need to cultivate a Middle Way between rebellion and conformity. Equally important, they need to be given what Michael Parenti calls “real history,” instead of the patriotic mush that passes for history in our schools. Divorced from the modern history of (Western) imperialism, philosophy — at whatever level — cannot hope to cultivate educated and virtuous citizens.

Stefan, could you say how teaching the history of imperialism, western or otherwise, would help to create “virtuous citizens”?

I can appreciate that some of what 2nd graders are currently taught would seem like what you call “patriotic mush” to adults, but we are talking about 7 year olds here. Would beginning their educations with a critique of their entire civilization really be something they can understand, or something that would have any effect other than making them feel unhappy and ultimately contemptuous of their own regime?

Part of what this article draws our attention to, in my opinion, is that there is a great difference between the virtues of a citizen and the virtues of a philosopher. You seem to regard them as identical. Is that the case, or have I misunderstood you?

The pathetic indoctrination of grade schoolers (and beyond!) needs to be counter-balanced by some truth. I am not advocating a blanket condemnation of the American democratic experiment. On the contrary. I applaud the ideals upon which this nation was founded, and students at all levels ought rightly to be versed in The Declaration of Independence and The Constitution and its amendments. I’m merely saying that students (and citizens generally) need to be well educated on the long history of the violation of those ideals, if they are to have any adequate understanding of the world in which we live, and any viable competence in responding to the challenges we face. Much progress has been made since the days of slavery. But contemporary “wage slavery” is a pernicious fact, both here and abroad. The U.S. maintains 800 military bases across the globe. Their primary function is to make the world safe for the Fortune 500. The American empire — the largest in world history — is itself a pernicious fact, silently overlooked in most American education; a nefarious economic drain on precious resources need for domestic improvement; and the primary reason America is the most hated nation in the world. Western “civilization’ has offered the world a lot in terms of progress, and also a lot in terms of tragedy. The stock market crash of 1929 was, perhaps, the single most contributing factor to World War 2, as it had devastating consequences not only here but also, and most importantly, in a Germany already reeling from the consequences of World War 1, and German citizens turned to Hitler because he promised them dignity and food. So, with regard to tragedy, and post-war Western imperialism (the British in India, for example), let’s recall a poignant moment in the life of Mahatma Gandhi. He was asked by a reporter: “Mr. Gandhi, what do you think of Western civilization?” Gandhi replied: “I think it would be a good idea.” One small example: the “Vietnam War” is a euphemism for America’s Indochina Holocaust (as if the genocidal bombing and destruction of Laos and Cambodia never occurred). As for your final and excellent question: No, I do not distinguish between the virtues of a philosopher and the virtues of a citizen. I here side with Socrates, Sartre, Camus, Russell, and Rorty. Philosophers need to bring their critical thinking skills to the marketplace of ideas; and to enhance their contribution therein by a perpetual, socio-political, historical self-education. If philosophers fail — as so many do — to commit themselves to the advancement of peace and justice, confining themselves instead, in their ivory (puzzle-palace) towers, to debating mostly among themselves, then we shall find ourselves entranced by what Hesse called “Glass Bead Games” until the society around us crumbles and we are thrust, too late, into the nightmare of history. I thank you for your stimulating “post,” and I hope this reply is adequately provocative and modestly satisfying.

You make a lot of interesting points. I’m not sure, for my part, that I’d put Socrates in with those other fellows, though. There are surely differences amongst the others as well (Sartre, Camus, Russell, and Rorty), but all of them embraced, to a considerable degree, the role of public intellectual. Indeed, each of them seemed to embrace some version of the idea that the role of philosophy is essentially public. Socrates seems to me profoundly different in this respect. His teaching appears to be that philosophy is a private undertaking. Now, it is obviously true that he was up to something in the marketplace, in the public sphere, but what? Mostly, it looks like he is trolling for a few other philosophic, or potentially philosophic individuals. Sometimes, frankly, it seems like he’s just goofing around. But, regardless, there really appears to be a pronounced difference between his private and public activities.

And this returns us to my last question, about the difference between the respective virtues of a citizen and a philosopher. Thank you for the kindness and candor in your response, by the way. It does seem to me like there is at least one respect in which the virtues of the two (citizen and philosopher) cannot be identical – that is, the virtue of a citizen must be relative, relative to the regime of which they are a citizen, whereas the virtue of a philosopher must be absolute, consisting above all in the possession of wisdom. Put in another way, a good citizen is a patriot, and a patriot gives his or her assent to the authoritative element(s) of the state or country or nation to which he or she is devoted. A philosopher need not give assent to such things. Indeed, a philosopher requires constant questioning, rather than assent to political principles.

Perhaps this problem could be partially resolved by placing the philosopher in a purely philosophic society. But the practical as well as the theoretical problems with that seem insurmountable to me. And even if it were possible, it would not really solve the problem. For there would still be other regimes, or other regimes possible, each of which would have their own good citizens, good according to the ideals which are authoritative within them. And so, even the philosopher in a philosophic city-state, whatever that might be, would only be a good citizen insofar as the city needs him not, nor makes any demands of him.

If I am right about this, then philosophy would truly be a problem for inclusion in the education of our young.

In an attempt to be even more succinct in making my point here, Stefan, to which I would, of course, be interested in reading your reply:

To say that the virtues of a citizen are identical to the virtues of a philosopher would, I believe, be the same as saying, in Socratic terms, that the noble is identical to the good.

Can that really be possible?

One of the most intriguing lines in Plato’s ” Republic” is where Socrates, in arguing for a Philosopher King (or Queen, or Council) to have absolute, monarchical authority in a “just” society, nevertheless notes that only in a democracy (where free speech is allowed and encouraged) can philosophy itself — as the dialogical pursuit of wisdom — actually flourish. Also, he’s quite wrong to assert (while in prison), in Plato’s “Crito,” that citizens must obey “the law” even if the law is unjust. Citizens are not obliged to obey social authority if social authority is immoral and perverse; on the contrary, in such a situation they have a democratic duty, as Jefferson said, to rebel. Meanwhile, Socrates is indeed occasionally goofy, even to the point of being sophistical while railing against the sophists. Yet his main concern was always virtue, which is why Plato identified Truth (and Beauty) with The Good. Since, as Socrates notes in Plato’s “Apology,” humans are not gods, hence perpetually troubled and imperfect, the pursuit of wisdom, hence virtue, is a perpetual task. George Allan offers a Socratic definition: “Virtue is the pursuit of virtue.” My point is that wisdom and virtue cannot be separated. Philosophy is — or ought to be — the journey from the love of wisdom to the wisdom of love. I suspect that Buddha, Jesus, Kant, Marx, and Jefferson would agree. James, Dewey,and Rorty too, in their pragmatic way. All argued forcefully against militaristic and economic imperialism. Yes, students and citizens need to obey rules and laws; but they also need to perpetually question authority and convention. So, yes, I would say that “the noble is identical to the good,” and all citizens are capable of being noble in that virtuous (Socratic and Judeo-Christian-Buddhist) sense. The most enlightened character in “War and Peace” is an illiterate peasant named Platon Karatayev. Tolstoy’s play on words is astute. To be good — virtuous, kind, generous, empathic, compassionate — is the ultimate path to, and expression of, wisdom. In sum, the meaning of life is learning and service. And only when citizens embody that ideal will a noble society be possible. We may never achieve the classless society inherent in the notion of The Peaceable Kingdom, but we should never cease to pursue it, perpetually shrinking the gap between rich and poor, protesting militarism and war, and, as Rorty said, “widening our circle of compassion.” There is, and ought to be, room for philosophy as a specialized, “academic” discipline, open to those who are temperamentally inclined in that direction. Meanwhile, philosophy as the love of wisdom manifest in the wisdom of love is a noble and necessary occupation for all — the foundation for a just society in which vocations and the arts of all sorts flourish. I thank you for your lucid and provocative questions, and the humility and kindness with which you express them. And while there are certainly important and profound differences between the “philosophers” that I mention, I string them together with the intention of referring to them when, as it were, they were at their best.

Very helpful remarks, again, thank you.

I do think, however, that wisdom must be separable from virtue, at least to some extent. That is, wisdom would appear to be a kind of virtue, not simply virtue itself. It might even be the highest virtue, which gives direction and order to all other virtues, but that would still not make it the same as virtue. For example, courage is a virtue too. But courage is not wisdom. Wisdom might require courage to attain it, and courage might require wisdom, lest it become mere recklessness. But they are not the same and they are both virtues.

I am still unclear as to how you think the kind of education (broadly speaking) that you are describing here would produce good citizens, or be appropriate for 2nd grade classrooms. This last seems important, at least to the extent that it was the concern of the original article above. Like you, I think, I lament the intellectual and spiritual condition of so many young people who are the products of the existing educational system. But I agree with the article, as I understand it, in thinking that the attempt to turn seven year old children into little philosophers, much less Socratic philosophers, would be a terrible mistake.

I do understand better now why you were stringing together the people you mentioned in the manner you did. Thank you for clarifying that.

Just one more thing on this (and you’ll excuse me, I hope, but I’m always at least trying to make things clear for myself):

You say that the noble and the good are identical. Isn’t that idea explicitly attacked by Socrates in the Apology, where he mocks his accusers for thinking that the education they provide for their children (usually by Sophists) will make them both “noble and good”?

Asked otherwise – doesn’t nobility require some measure or type of sacrifice, usually of one’s own good, out of devotion to a cause or principle higher than oneself? It seems to me that goodness makes no such requirement.

I should have mentioned Emerson (and Lao Tzu) too. Meanwhile, here’s a relevant quote from Socrates in Plato’s “Crito” — “Whoever harms another harms himself.” Accordingly, I think it’s fair to say that Socrates does indeed offer a definition of virtue (and, by extension, wisdom). And isn’t that what all parents and teachers need to teach — and citizens, stockholders, CEOs, and politicians embody by example?

I should have mentioned Emerson (and Lao Tzu) too. Meanwhile, here’s a relevant quote from Socrates in Plato’s “Crito” — “Whoever harms another harms himself.” Accordingly, I think it’s fair to say that Socrates does indeed offer a definition of virtue (and, by extension, wisdom). And isn’t that what all parents and teachers need to teach — and citizens, stockholders, CEOs, and politicians embody by example?

Without getting too deeply into the Crito here, I will say that Socrates furnishes abundant reasons in that dialogue to suspect that the teaching you mention is far from his final position on the matter.

But, regardless, the idea that a crime is it’s own punishment, or, put somewhat differently, that in harming someone else you are also harming yourself, is a problematic view in so many ways. I will mention just a few.

In the first place, it presents itself as a statement of fact, rather than a normative statement, or a moral imperative. If it were true, then it would simply be the case. And we would see a lot less injustice, because the people harming others would be suffering for it themselves and would be disinclined to act in the ways they had previously.

It also takes the bite out of our criticisms of unjust people, doesn’t it? For example, if we suggest, as I think you did, that citizens, stockholders, CEOs, and politicians sometimes or often act in ways that are harmful to the rest of us, then we can rest assured that the primary harm they have caused is to themselves.

I suspect that not only are some of these people doing more harm to us than themselves, but that, in fact, they are aggrandizing themselves by acting as they do, and not harming themselves at all. That would appear to be at least one of the major incentives to them for continuing to pursue their particular ways of life.

None of this is to say that I don’t think something like the maxim you offer about self harm would be out of place in the education of our young. A version of it would probably be quite salutary and helpful. I do wonder, though, if a reaffirmation of it’s related Jewish and Christian variants might not do the trick. What do you think? In those versions, it does indeed sound more like a moral command. The versions I have in mind are Hillel’s teaching that, “What is hateful to you, do not do to your fellow…”, or Christ’s later alteration of it, “Do to others what you want them to do to you”.

Plato argues that justice is a synthesis of courage, wisdom, and temperance. His proposal applies existentially and socially, insofar as “society is man writ large.” If microcosm mirrors macrocosm, then the reverse is also true. The individual psyche is a set of forces, and so is any social group (however small or large), and they “reflect” and influence each other in profound and crucial ways. Thus Jung and Buddha, and Lao Tzu, with Judeo-Christian variants: There will be no social peace, and no world peace, without inner peace. But where is “virtue” in Plato’s formula? Is it the same as “justice”? Merely implicit therein? Spread across the tripartite synthesis? These remarks and questions are a roundabout way saying: You are correct; I agree with you. There are many kinds of virtue, and many kinds of nobility, just as there are many kinds of justice, and many kinds of more or less adequate, pragmatic, viable education. You consistently raise excellent questions, and concisely so, with both charity and sincerity, as befits an authentic, “Socratic” philosopher. Your elenctic provocations require me to admit that simple formulas hide deep and complex issues inviting honest and sophisticated scrutiny. Accordingly, teaching philosophy to grade schoolers would indeed be challenging, and raises a host of important questions regarding both method and content, with the aim, hopefully, at increasing levels, of teaching them to be “critical thinkers” and responsible and self-educating citizens. Second: Hegel notes that brutality brutalizes the brute, not merely the victim. In this he echoes Socrates, Jesus, and Buddha. Third: You are quite right that in daily experience, brutes too often get away with all kinds of violence, seemingly with no harm to themselves, and often with profit and power as their rewards. Hence, for the law of karma (“As you sow, so will you reap.”) to make any viable sense — at least in the long run, beyond the more immediate and pragmatic point that kind people are generally far happier than people prone to violence, and honest people tend to be more content than those prone to habitual deceit — one would have to embrace the Pythagorean and Buddhist notion of reincarnation. This is a notion difficult for Western folk to embrace, mainly due to social conditioning, religious dogmatism, and a more or less consistent refusal to meditatively plunge into the deeper depths of the psyche (where Platonic “recollection” is catalyzed by a yinful quieting of what “The Lotus Sutra” calls “monkey mind”). Seeking satisfaction in the outer carnival, we miss the inner festival (where moral and karmic lessons become increasingly clear). We need to teach grade schoolers how to meditate (becoming zenfully centered and peaceful) at least as much as we need to teach them to be “critical thinkers.” This is the “Socratic turn” (zenfully inward) too often missing in discussions of teaching children (future citizens) to be Socratic, philosophic, thoughtful, logical, questioning, “critical,” and “virtuous” (insofar as that term implies both ethics and what Plato says of Socrates: sophrosyne, for which the Buddhist term is upeksha, and both of which mirror Eckhart’s Gelassenheit and what Taoists call wu-wei). I think there are profound “Jewish and Christian variants” of the Buddhist worldview (moral and karmic), and this is indeed one of the most important and fruitful dialogues in the world today. So: Bravo to you! It’s a pleasure to be questioned by a kindred soul. … PS: Arnold Toynbee, when he was asked what future historians would say was the most important event of the 20th century, replied: “The introduction of Buddhism to the West.” This was around the same time that Einstein declared that of all the world’s religions — i.e., as a worldview and way of life — Buddhism holds the most promise of putting us, collectively, on the track toward world peace. Toynbee and Einstein understood our cataclysmic trajectory. Their hope was not that Buddhism would introduce us to a new way of thinking and behaving; rather, they hoped (as I do) that it would return us — in all our activities and institutions — to the moral heart of the Torah, the main message of Jesus, and, I dare say, the simplicity, courage, and pursuit of virtue embodied by Socrates. Note, too, that Plato was right to assert, in “The Republic,” that the only hope for a “just society,” however tenuous and precarious, was to separate money from politics, the fusion of which is the curse of the postmodern world, haunting and undermining us now, just as it has throughout what Hegel called “the slaughter-bench of history.” It seems increasingly clear that our only hope for survival is, in Chogyam Trungpa’s words, to “reclaim the sanity we were born with.” This requires what I have herein called “the Socratic turn,” and which Toynbee and Einstein understood as precisely that which Buddhism offers, and which, at its best, returns us to the “Jewish and Christian variants” of “the two wings” of Buddhism: wisdom and compassion (prajna and karuna).

I confess that I am not very familiar with Buddhist thought. So I thank you for drawing my attention to some of these things and I’ll spend some time considering them. I have enjoyed our exchange here immensely.

I will mention just one point in your most recent comment, one which is actually a recurring point there, that I find difficult to understand, and that pertains to the matter of the “Socratic turn”.

To my knowledge, the “Socratic turn” refers to that time in Socrates’ life when he reoriented both himself and his general manner of inquiry into the nature of things. He turned from his concern with physics (or natural science) to an examination of speeches.

Of course, to understand what is at stake in this “turn”, a great deal more would have to be said. But in your comment, you indicate that the “Socratic turn” is to be identified with Zen meditation, in one instance, and a recovery of sanity, in another. With regard to the former, it is very difficult for me to see how the examination of accounts is akin to mediation. You might well have some particular linkage in mind, and it might be an important one, but it is not apparent to me what it is. With regard to the latter, I think we probably agree – the “Socratic turn” is analogous, in an important way, to a restoration of sanity. I am not sure that sanity as Socrates is held it is quite the same as what Chogyam Trungpa’s version of it, but I am unfamiliar with the second and will have to look into it.

Thank you again for a rewarding discussion.

As always, I find your discourse pleasantly provocative and illuminating. As Plato says: “Discourse is the highest form of philosophy.” That’s clearly a main reason why his writings (except for The Letters and The Laws) are dialogical. That plus the fact that he abandoned plans for a political career, turning instead to philosophy, as a result of his stimulating conversations with Socrates. I’ll comment on The Socratic Turn in a moment. First, though, kindly allow me to recommend “Living Buddha, Living Christ,” by Thich Nhat Hanh; “Seth Speaks,” by Jane Roberts (skipping all the obtrusive interruptions, while keeping a really open mind, and recalling that Blake said “the paranormal is normal”), and Janwillem van de Wetering’s “AfterZen” (out of print, but good copies available cheaply on Amazon). Hanh’s book shows that Jesus and Buddha were, as it were, Soul Brothers. “Seth Speaks” is the best book I have ever read in 50 years of philosophizing: the most philosophically and psychologically illuminating, and confirming much of my own experience. Van de Wetering’s book is an earthy, lucid, humorous, autobiographical, story-telling introduction to Buddhism in general and Zen in particular. You have my email address; let me know if you want more suggestions, or wish to continue our conversation. Now, The Socratic Turn is indeed double-pronged. Abandoning his (“scientific”) investigations of nature, he turns, on the one hand, as you note, to language, speeches, rhetoric, “giving accounts.” On the other hand, he turns inward, toward the psyche: its depths, mysteries, complexities, intuitions, voices, revelations, and wisdom. In a sense, then, The Socratic Turn is dialectical. He goes from outward to inward investigation, then back toward a Middle Way: with a focus on language, logic, and virtue. Indeed, The Socratic Turn might best be described as tripartite: psychological, linguistic, and ethical. Also, it propels him existentially: toward an emphasis on self-actualization. Maybe Jung was right: “Trinity seeks completion in quaternity.” So perhaps the most adequate way of thinking about The Socratic Turn is to view it as having, simultaneously, four vectors: psychological, linguistic, ethical, and existential. Hope this helps. And thanks again for stimulating my own qualifying clarifications. … PS: Note that Socrates says in “The Phaedrus” (and elsewhere) that he pays acute and fruitful attention to his dreams, his inner voice, and the whisperings of nature. And when he famously goes into occasional trance, standing still and silent for hours, it’s worth wondering if he’s not confirming for himself the Heraclitean dictum: “No matter how far you travel, you never reach the end of psyche.” Such silent self-exploration, and self-revelation, is also what occurs in Zen meditation, especially at its deepest levels; and this is both augmented and expedited in Tantric yoga, and experientially confirmed by those who have the courage and persistence to cultivate “lucid dreaming.”

Thanks again… I will certainly look into some of the books and thinkers that you have mentioned.

I must add that I am somewhat concerned with a number of the things that you attribute to Socrates. You are, of course, correct that Plato presents Socrates as occasionally standing still, as if in deep contemplation, and that Socrates says all sorts of things about listening to nature (although he says that nature is too far beyond him), listening to his inner voice (although that voice appears mostly just to counsel him to observe his own interest), and even speaking to a “daimon” and following the gods (although these things often seem quite ironic).

It is hard to impart more to these characterizations of Socrates than is actually there. Neither Plato nor Socrates mention meditation and, although they do discuss contemplation, that seems like a different sort of thing to me. Socrates also does not seem genuinely pious. And even his “daimon” does not appear to give him moral counsel.

I am not necessarily in disagreement with you here, and what you have to say is very helpful to me. I am only concerned that we do not impart to Plato’s description of the life of philosophy things that do not properly belong to it.

It might well be the case that something like the things you describe is implied by omission in the portrait of Socrates, but I’m not sure about that – so many things could be implied by omission. It might also be that there are inadecquacies in Socratic philosophy that necessitate the addition of Buddhism in general, or Zen in particular. That is something I will have to think much more about. I promise I will do so!

I agree that we ought not “impart to Plato’s description of the life of philosophy things that do not properly belong to it.” Still, Plato’s philosophy, in its various modes and in its evolution, is more suggestive than doctrinaire; more a set of questions than a rigorous system, as Whitehead notes. Authentic Socratizing is philosophy as ongoing conversation, not dogma. I feel that our discourse happily meets that description. Now, four points might help. First, you are correct to note that Socrates (in Plato’s dialogues) does not evidence much interest in nature as such; after rejecting the speculations of Anaxagoras, he launches upon his “second sailing,” which I call the “Socratic turn” toward psychology and ethics. Second, I have my own experiential version of the Socratic voice, which guides me in ways far more explicit that merely saying No to a possible misstep. I have been much rewarded by its wisdom; and have all too often paid dearly for not heeding its guidance. I do not pretend to understand the full dynamics of this phenomenon, but I am also not completely in the dark, thanks largely to the Seth and Castaneda books, and those by Alice Bailey. (Maybe we could talk more privately about this, if you wish. My email is stefanschindler@comcast,net.) Third: About three years ago I was speaking to a philosophic colleague about the parallels between Buddhism and quantum physics, and he exclaimed: “They’re not even talking about the same thing!” Alas, he knows little about Buddhism, and has never attempted meditation. His response still strikes me as all too typically Western, Cartesian, dualistic, dogmatic. I suggest, instead, that deep voyaging in the psyche may well produce insights into the (quantum-holistic) nature of reality. Even without meditation, a study of certain basic Buddhist ideas, like “emptiness” (shunyata — absence of any independent, self-sustaining selfhood or “substance”) and “interbeing” (pratitya-samutpada — “dependent co-origination”), shows remarkable parallels to quantum physics. Which is to say: Buddha had a lot to say about the nature of appearances (partly expressed in the difference between samsara and nirvana, and in Nagarjuna’s distinction between “provisional” and “ultimate” reality). See, for example, Graham Smetham’s “Quantum Buddhism,” as a long, provocative, superb preliminary to the study of Buddhist sutras with an eye to modern scientific parallels. Or, to put it another way: Dualism is the fatal flaw of Western culture. There is, currently, a philosophic and scientific backlash against books like “The Tao of Physics,” but I take this to be the all too typical onto-epistemological Ostrich sticking its head back in the sand. Fourth, and this is likely the most important point: Modernity needs interiority. Without that inner (meditative) anchor, we are, collectively, racing toward our doom in an endless frenzy of competition and consumerism. Buddha’s lesson for today? “Beware the Samsaric Uroboros. The profit-driven Zeitgeist consumes itself.” I put these last two sentences in quotes because they are taken from an article I am writing (for Political Animal Magazine) on “Buddha’s Political Philosophy.” I was invited to write this article by the editors of this on-line journal; and they extended that invitation after reading the extensive discourse you and I have been fruitfully engaged in. So I thank you again for your stimulating questions and always humble and courteous Socratizing. Kindly forgive my long delay in responding to your comments immediately above, as I have been busy with multiple drafts of the upcoming article (which should appear in the next month or two).

The “Howl” that begins this column contains an excellent question: “Is philosophy really good at creating a civil society?” I think it should be, but the actual answer is: Not necessarily. The question reminds of the 1970s and ’80s when John Silber was president of Boston University. Silber was an academic, “professional” philosopher down in Texas, brought to Boston to preside over BU. But instead of helping BU become a model of a “civil society,” Silber was an arrogant, condescending, power-hungry ego maniac who instilled at BU an atmosphere of what one journalist called “fear and loathing.” He insulted students, hated Howard Zinn, called Noam Chomsky a liar to his face on national television, treated BU’s clerical, janitorial, and food service staff as peasants unworthy of a living wage, and generally thought of himself as a “philosopher king” in the Platonic mold while violating the spirit of that Platonic ideal by enriching himself at the expense of BUs faculty, staff, and students. He was more like Dick Cheney than Socrates, committed more to power and wealth than virtue and service. I was teaching philosophy at the time (at Berklee College of Music), and I was embarrassed by Silber’s arrogance, greed, and neo-fascist interpretation of Plato’s philosopher king. So becoming a “professional” philosopher in no way guarantees becoming a decent human being and a model for a civil society.

The “Howl” correctly asserts that schools should do more to enhance critical thinking skills and to provide students with “exposure to serious issues.” Certainly one of the more serious issues to be rectified is historical illiteracy. This country has betrayed every ideal it ever pretended to stand for; and without understanding that basic fact, students will not have the critical thinking skills necessary for intelligent voting. Philosophy as such may be too sophisticated for grade schoolers, but from junior high school forward, they ought, at the very least, be exposed to the writings of people like Gore Vidal, Noam Chomsky, Howard Zinn, Michael Parenti, Lewis Lapham, William Blum, Norman Mailer, Richard Rorty, and the activism and moral philosophy of Mother Jones, Emma Goldman, Dorothy Day, Helen Keller, Molly Ivins, Barbara Erenreich, and others in the authentically progressive and liberal movement. In short, critical thinking skills without honest history is like Kantian concepts without relevant percepts.

Too many academic philosophers fail to instill in students a sense of relevant social history and immediate applicability. A few years ago I was listening to a set of lectures by a brilliant philosopher at the University of Pennsylvania who paused to admit that 9/11 came as a total shock. It never occurred to him that the USA might be hated for good reason; and it was obvious that he had no comprehension of why the CIA, decades ago, invented the term “blowback” as a cautionary warning against the inevitable consequences and dangers of American imperialism.

The morality tale relevant here is Herman Hesse’s “Glass Bead Game.” Philosophy is too often merely an exercise in intellectual masturbation. It ought, rather, to be a vital stimulant in the marketplace of ideas; and that means firmly tethering the love of wisdom to the ongoing challenge of creating a sane and humble society rooted in civil justice.

In my modest list of historians, journalists, and social philosophers, I should have included John Pilger, whose articles, books and videos are admirably lucid and heart-breakingly illuminating. I do, however, mention him in my book AMERICA’S INDOCHINA HOLOCAUST: THE HISTORY AND GLOBAL MATRIX OF THE VIETNAM WAR. Meanwhile, although it’s true that too many professional philosophers remain woefully ignorant of America’s imperial machinations (a euphemism for war crimes), it’s also true that philosophers’ attempts to be more active in the marketplace of ideas are perpetually thwarted by the mainstream media, especially if those attempts are leftist in leaning. (This is less true in Europe, as evidenced by France’s refusal to participate in the Bush-Cheney invasions of the Middle East, and where Germany’s participation was reluctant and nominal at best.) Not even Nixon prepared us for the criminality of the Reagan administration; and not even Reagan prepared us for the moral, military, and financial obscenity (not to mention strategic lunacy) of Bush-Cheney. With mainstream media complicity, Reagan turned “liberal” into a dirty word, and the phrase “liberal media” is one of the most popular and pernicious lies still in currency. If America’s marketplace of ideas and mainstream news media were authentically liberal, Reagan would never — could never — have become president. Now, given that Bush, Cheney and cohorts lied about about almost everything else (as recommended and institutionalized by Newt Gingrich, the living definition of Sophist and proud of it), it’s astonishing how many people — including philosophers too ignorant, mesmerized, or cowardly to engage in actually critical scrutiny — still believe the Bush-Cheney version of 9/11. Or rather, it’s not astonishing, given that the mainstream news media is a government lapdog, having long ago betrayed its democratic mission as watchdog. So, yes, American democracy is now more in peril than ever; and, yes, OK: That’s my howl of the day.