By: Kiki Berk An essay from 1000-Word Philosophy

“Hell is other people” is a famous line from No Exit (1944), a philosophical play by the French existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980). No Exit is popularly understood as arguing that human relationships are essentially fraught with conflict. This interpretation seems to be supported by Sartre’s pessimistic discussion of relationships in Being and Nothingness (1943), his most famous philosophical work.

This essay explains why this pessimistic interpretation of Sartre is mistaken. A careful examination of Sartre’s work shows that he was far more optimistic about relationships than his classic one-liner has led many people to believe.

1. No Exit

No Exit opens with its three main characters—Garcin, Inez, and Estelle—being led into an old-fashioned living room. They don’t know each other, but they do know that they’re dead and now in hell. Hell isn’t what any of them expected, however. Where are the horned devils with pitchforks? After quickly getting on each other’s nerves, Inez realizes the truth about their situation: “Each of us will act as torturer of the two others.”[1]

To see how this works, let’s consider Garcin. Garcin is a journalist who fled the war, he says, on account of his pacifism. But he worries that the real reason he fled is because he’s a coward. He needs someone to assure him that this isn’t true. He tries to get this assurance from Estelle, but her opinion of him is worthless, he soon realizes, for she would say anything for a man’s affection. Garcin next pins his hopes on Inez, who isn’t interested in men, but her jealous and sadistic nature leads her to simply refuse Garcin’s request to be dubbed a hero. Thus, Garcin is effectively tortured by the other two, with no way out, prompting him to exclaim: “Hell is other people!”[2]

2. Being and Nothingness

In his difficult work Being and Nothingness, Sartre paints a bleak picture of human relationships.[3] He says that relationships involve a constant struggle over freedom, which is the only thing that really matters.[4] This tension arises because we either treat other people as objects (which undermines their freedom), or we allow ourselves to be treated as objects by them (which undermines ours). Either way, someone’s freedom is threatened, so encountering another person necessarily results in a struggle for dominance. Thus, Sartre’s pessimistic view of relationships seems to be grounded in his broader philosophy.

3. Misinterpretation

While Being and Nothingness seems to support the popular interpretation of No Exit, according to which relationships are always bad, this interpretation faces a serious challenge. In an oral preface for a 1964 recording of the play, Sartre claims that his statement “hell is other people” has been commonly misunderstood.[5] In his words:

It has been thought that what I meant by that was that our relations with other people are always poisoned, that they are invariably hellish relations. But what I really mean is something totally different. I mean that if relations with someone else are twisted, vitiated [i.e., corrupted], then that other person can only be hell.[6]

In other words, according to Sartre, the statement “hell is other people” is implicitly conditional: other people are hell for us if our relationships with them are bad. He explains further:

If my relations are bad, I am situating myself in a total dependence on someone else. And then I am indeed in hell. And there are a vast number of people in the world who are in hell because they are too dependent on the judgment of other people. But that does not at all mean that one cannot have relations with other people. It simply brings out the capital importance of all other people for each one of us.[7]

According to Sartre, other people’s judgments invariably enter into our thoughts and feelings about ourselves. This isn’t bad in itself, for without these judgments we couldn’t truly know ourselves. What’s bad is when we allow ourselves (like Garcin) to become overly dependent on the opinions of other people. This leads to those people being “hell” for us. But although other people can be hell for us (if we relate to them in this way), they needn’t be (if we don’t).

4. Bad Faith

How does this conditional reading of “hell is other people” fit with Sartre’s pessimistic account of relationships in Being and Nothingness? The key to answering this question lies in a footnote at the end of his discussion of human relationships:

These considerations do not exclude the possibility of an ethics of deliverance and salvation. But this can be achieved only after a radical conversion which we can not discuss here.[8]

The “radical conversion” to which Sartre refers is a transformation from “bad faith” to authenticity, which is at the very core of his existentialist philosophy. People are in bad faith when they deceive themselves into thinking they aren’t ultimately free and responsible for their actions. Making excuses for what one does, inaccurately labeling oneself, inventing a role in order to hide behind it (as Garcin does)—these are all ways of being in bad faith.[9] Relationships between people who are in bad faith are bound to fail; relationships between people who are authentic, however, can succeed.

5. Heaven is Each Other

Unfortunately, Sartre never tells us what it takes to undergo this “radical conversion” from bad faith to authenticity. All he tells us is that he’ll tackle this problem in a later work, which he began but never finished.[10] But he did continue to think about relationships. In a 1971 interview, when asked about his statement that “hell is other people,” he responds:

But that’s only that side of the coin. The other side, which no one seems to mention, is also “Heaven is each other.” … Hell is separateness, uncommunicability, self-centeredness, lust for power, for riches, for fame. Heaven, on the other hand, is very simple—and very hard: caring about your fellow beings.[11]

So, even late in his life, Sartre still thinks that relationships can succeed.[12]

Notes

[1] Sartre 1989: 17.

[2] Sartre 1989: 45.

[3] Sartre discusses relationships in Chapter 3 (“Concrete Relations with Others”) of Part 3 (“Being-for-Others”).

[4] Sartre discusses freedom in Chapter 1 (“Being and Doing: Freedom”) or Part 4 (“Having, Doing, and Being”).

[5] Sartre – L’enfer, c’est les autres “Explications.”

[6] Sartre 1976: 199.

[7] Sartre 1976: 199-200.

[8] Sartre 1958: 412.

[9] Sartre discusses bad faith in Chapter 2 (“Bad Faith”) or Part 1 (“The Problem of Nothingness”).

[10] Extensive notes for this unfinished work were posthumously published as Notebooks for an Ethics.

[11] Sartre in Gerassi 2009: 130.

[12] Large portions of this essay were previously published in my chapter, “Is Hell Other People?” in The Good Place and Philosophy: Get an Afterlife. Thanks very much to Open Court for its permission to re-use this material here.

References

Berk, Kiki. 2020. “Is Hell Other People?” In Benko, Steven and Andrew Pavelich (eds.). The Good Place and Philosophy: Get an Afterlife. Chicago: Open Court.

Gerassi, John. 2009. Talking with Sartre: Conversations and Debates. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Sartre, Jean-Paul. 1958. Being and Nothingness. London: Routledge.

Sartre, Jean-Paul, Michel Contat and Michel Rybalka (eds). 1976. Sartre on Theater. London: Random House.

Sartre, Jean-Paul. 1992. Notebooks for an Ethics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sartre, Jean-Paul. 1989. No Exit and Three Other Plays. New York: Vintage.

Related Essays

Existentialism by Addison Ellis

Camus on the Absurd: The Myth of Sisyphus by Erik Van Aken

Hell and Universalism by A. G. Holdier

What Is It To Love Someone? by Felipe Pereira

Dr. Kiki Berk is an Associate Professor of Philosophy at Southern New Hampshire University. She received her Ph.D. in Philosophy from the VU University Amsterdam in 2010. Her research focuses on Beauvoir’s and Sartre’s philosophies of death and meaning in life. k.berk@snhu.edu

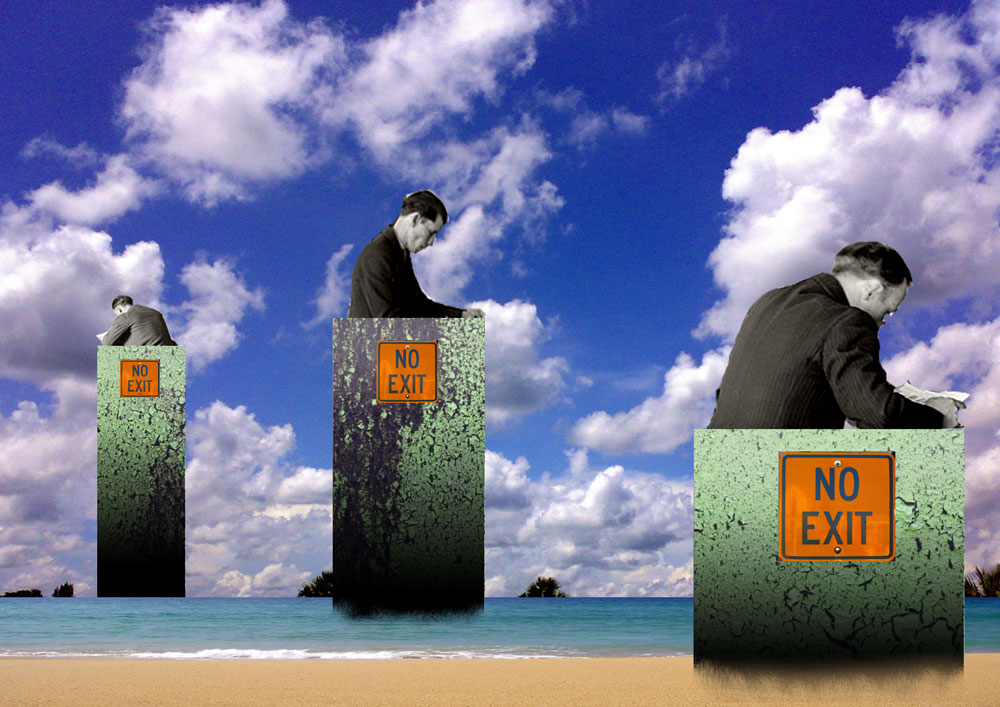

Image: No Exit, by Ubé, via Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Bravo !! Very nicely done, and right on target. A lucid and important synopsis, with which I have long agreed. It’s the way I taught Sartre in my 40-year philosophy and psychology teaching career. Thank you for such a concise and cogent essay, and thanks also to Political Animal for posting it.