By: Dennis Rohatyn

The second impeachment trial has given us the opportunity to learn something about ourselves.

Rep. Raskin is quite right to call Donald Trump the “inciter-in-chief.” Yet there is a fine irony to his words. The analogy between “shouting ‘fire!’ in a crowded theatre” and Trump’s role in sparking insurrection, then spreading and fanning the flames, shows that Trump poses a clear and present danger to national security, on par with what Justice Holmes ruled at the moment he coined the phrase [Schenk vs. US(1919)], a century ago. Yet Holmes changed his mind about that, only a few months later [Abrams vs. US (1919)]. For by then it was clear that “Socialism” was not the enemy, but that Pres. Wilson was largely to blame for the aftermath of Versailles, both at home and abroad. After those verdicts, the ‘clear and present danger’ criterion remained, but the search for “anarchists” and “Bolsheviks” as convenient scapegoats for our domestic problems ceased, albeit only temporarily.[1]

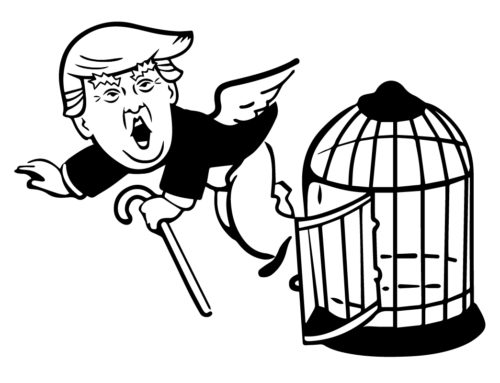

Now it is Trump, for whom scapegoating is second nature, who is at last getting his comeuppance as a live threat to the very existence of the republic. Those who live for Schadenfreude, die for a cheap sado-masochistic thrill, only to come back for more.

In that regard, it is grotesquely fitting that Larry Flynt died on the same day as Rep. Raskin refuted the “first Amendment” defense that Trump’s august attorneys, no strangers to the discourse of obscenity trials, hastily proferred on behalf of their new client. So the debate unfolded, without even mentioning the dividing line between free speech (“liberty of thought and action,” as John Stuart Mill called it) and public conduct requiring the “enforcement of restraints upon the actions of other people.”[2] The fundamental principle of any free society is that for every legal or moral right there is a corresponding duty. That applies to everyone, regardless of rank.

Even in the land of exceptionalism, or one where a President willfully makes himself the exception to every rule, there can be no exceptions to that rule, without destroying all pretense to self-government. Donald Trump didn’t just violate an oath to defend the Constitution; he violated the axiom of civility, which is universally binding, in the same way as equality before the law, if that be taken seriously. Hence there is no need to exempt Trump in order to prove his guilt, or to make him special, thanks to his role as an elected official. He may be ‘first among equals’ but unless he is equal, he can’t be first, except for being worst. If he harms others (or fails to protect them) in word and deed, then he is guilty, both of sticks and stones and breaking verbal bones—no bones about it. Hate speech is a crime, in and of itself. Multiply it by its effects, or raise it to the proper exponent, and the damage is proportional to the crime—in this case, incalculable.

That is just one of the many lessons to be learned from the spectacle that we are allowed to witness. Perhaps the Senate should recess until everyone who speaks has learned to think, as well as read. Then we may be spared the indignity of hearing arguments that are both false and self-refuting,[3] while wondering why the ‘cunning of dialectic’ can be so cruel and consoling, simultaneously.

Karl Marx was wrong: history begins as farce, yet invariably ends up as tragedy. The law of unintended consequences inters the rest.

References:

[1] Holmes’ eloquent dissent in Gitlow vs. New York (1925) offered a second chance to make amends. It came too late to save Gitlow, who became a victim of the “bad tendency” test, which was both arbitrary and an unwitting example of its own standard. Eventually, the Court learned its lesson, though it took the Pentagon papers case (NY Times vs U.S. (1971)) to do it. Yet the CPD criterion endures, despite the infrequency of its use. Now is the right time to invoke it—and to redeem it.

[2] John Stuart Mill, On Liberty [1859], Ch. I; ed., intro. Alan Ryan (New York, 2006), 11.

[3] For example, the claim that Trump can’t legally be tried, since he is no longer President. The obvious answer is that he was President when the Article of Impeachment was passed; indeed, the impeachment clock began ticking on January 13. The actual trial date is purely a matter of scheduling, hence irrelevant. “Constitutionality” is a red herring. So is the argument that the President has already been “removed” from office. The point is to prevent him from trying to regain it—that is, to compel him to forfeit his eligibility to run for (re-)election at a later date. Impeachment has a future referent. But the acts themselves occurred while he was in office.

A native New Yorker, Dennis Rohatyn took his PhD at Fordham. He moved to the West Coast in 1977. His works include “Out of My Mind,” “The Flight of Theory”, and “Cartesian Requiem.” He writes about everything, but his true vocation is the inhuman condition.

Image: PAM illustration

Leave A Comment