By: Hendrik van der Breggen

Do two wrongs make a right? Nope. It’s a fallacy—a mistake in reasoning.

Philosopher Trudy Govier, in her university-level critical thinking textbook A Practical Study of Argument, describes the fallacy of two wrongs make a right as follows:

Fallacy of two wrongs make a right. Mistake of inferring that because two wrong things are similar and one is tolerated, the other should be tolerated as well. This sort of argument misuses the appeal to consistency. This fallacy is often simply called two wrongs.1

The mistaken reasoning runs like this: Two actions are similar and wrong, but we allow or tolerate one, so, to be consistent, we should also allow or tolerate the other one, i.e., the one I’m thinking about doing (or have done). The problem, however, is that the consistency goes the wrong way! If the action that’s tolerated is wrong, then it shouldn’t be tolerated—and neither should the action I’m wondering about or attempting to justify.

Here’s an example that should help illustrate the error, from philosopher T. Edward Damer’s book Attacking Faulty Reasoning, but slightly modified by me (in an attempt to add some humor):

Background: A father and son are out for a drive, with dad driving.

Father: Son, I really don’t think you should drink and drive.

Son: Why not? You’re driving with a martini in your hand.2

Clearly, neither the father nor the son should drink and drive! If drinking while driving is wrong (which it is), it’s wrong for both of them.

Govier provides a more serious example and helpfully explains the problem:

“Animals are ill-treated when they are raised for food, so it is all right for animals to be ill-treated when they are kept in zoos.” Two-wrongs arguments misuse analogy. If the treatment of animals when they are raised for food is indeed wrong, and the treatment of animals in zoos is indeed relevantly similar to it, then the proper conclusion is that reform is needed in both cases. It is not that the second wrong is somehow justified in virtue of the fact that the first one has been permitted to persist.3

Here’s another example: “What’s the big deal if Canadian military prisons engage in torture? Similar stuff occurs in many countries around the globe.” Surely, the wrongness of torture elsewhere doesn’t make torture here okay.

Here’s another example: “He stole my car. So it’s okay that I steal his car.” Surely, the wrongness of one theft doesn’t justify another theft. Historically, relying on two-wrongs-make-a-right reasoning often leads to ongoing and escalating feuds.

Here’s another example: “Other people harmed my ancestors, friends, and family who are innocent, so it’s okay for me to hurt other innocent people by looting and rioting and killing them.” Surely not. To borrow (and liberally embellish) a comment from American conservative commentator Candace Owens, if your response/solution is as bad as (or worse than) the problem (which is bad), it’s not a solution—and it’s not good.4

Govier helpfully explains the problem of the two-wrongs-make-a-right fallacy:

[Two wrongs is] a misplaced appeal to consistency. A person is urged to accept, or condone, one thing that is wrong because another similar thing, also wrong, has occurred, or has been accepted and condoned…. The two-wrongs argument seems to rely on the supposition that the world is a better place with sets of similar wrongs in it than it would be with some of these wrongs corrected and the others left in place. It is not justifiable to multiply wrongs, or condone them, in the name of preserving consistency.5

Govier adds:

If one practice is wrong and another is relevantly similar to it, then a correct appeal to consistency will imply that the other is wrong too. Two wrongs do not make one right. Two wrongs make two wrongs. There is no ethical or logical justification for multiplying wrongs in the name of consistency. Consider two proposed actions: (a) and (b). If both are wrong, and similarly wrong, then the best thing would be to prevent both from occurring.6

Two wrongs don’t make a right. 7,8,9

NOTES

- Trudy Govier, A Practical Study of Argument, 7th edition (Belmont, California: Wadsworth/ Cengage Learning 2010), 391.

- T. Edward Damer, Attacking Faulty Reasoning, 2nd edition (Belmont, California: Wadsworth, 1987), 109. In Damer’s original, the father is merely standing with a martini in hand, not driving. This particular instance of the fallacy could also be understood as the fallacy of tu quoque (Latin for “you too,” i.e., you do the same thing, so it’s okay that I do it). The reason drinking and driving is wrong is because alcohol consumption dangerously impairs driving skills. (So, to be clear, the reason for not drinking and driving isn’t Michael Scott’s reason: “do not drink and drive, because you may hit a bump, and spill the drink.” Yes, another attempt at humor.)

- Govier, A Practical Study of Argument, 385.

- Candace Owens, “BLM Riots Destroy Black Communities,” PragerU video, June 29, 2020. What Owens actually said: “If your solution is worse than the problem, it’s not a solution.”

- Govier, A Practical Study of Argument, 385.

- Govier, A Practical Study of Argument, 341.

- Some readers might be inclined to think that the nature of ethics (what’s right and wrong) is wholly determined by agreements or contracts. This view of ethics is known as contractarianism and is deeply problematic. Why? Because some things are clearly wrong, period, regardless of contracts or agreements. For further critique of contractarianism, see my column Morals By Agreement?

- Also, some readers might be inclined to hold the ethical theory that the end (i.e., an ultimate and allegedly good goal) justifies the means (e.g., doing some wrongs to get to the goal), so whatever gets us closer to the end/goal is moral. In other words, on this view it’s okay to achieve an end/goal “by any means necessary.” This is a theory of ethics called utilitarianism. The standard problem of utilitarianism is the problem of justice: obvious injustices are allowed as a means to usher in the ultimate goal. Think of totalitarian communist regimes and the injustices they incurred (e.g., gulags, mass starvation) in their attempts to usher in their utopian societies. For a critique of utilitarianism, see my column On Utilitarianism.

In recent and related news, it may be of interest to note that Hawk Newsome, president of Greater New York Black Lives Matter, seems to hold to a utilitarian view of ethics: the end/goal is whatever his BLM organization holds dear, which can be achieved “by any means necessary” (Newsome’s words). Also of interest is that Mr. Newsome seems to hold to two-wrongs-make-a-right reasoning: violence (wrong) done by others seems very much to justify violence (wrong) from BLM. For more on Hawk Newsome’s views, see the article, If change doesn’t happen, then ‘we will burn down this system’. From the article:

The president of Greater New York Black Lives Matter [i.e., Hawk Newsome] said that if the movement fails to achieve meaningful change during nationwide protests over George Floyd’s killing by Minneapolis police officers, it will “burn down this system.”

“If this country doesn’t give us what we want, then we will burn down this system and replace it. All right? And I could be speaking figuratively. I could be speaking literally. It’s a matter of interpretation,” Hawk Newsome said…

“I don’t condone nor do I condemn rioting,” Newsome continued…

MacCallum [an interviewer] asked Newsome what Black Lives Matter hoped to achieve through violence.

“Wow, it’s interesting that you would pose that question like that,” Newsome responded, “because this country is built upon violence. What was the American Revolution? What’s our diplomacy across the globe?”

“We go in and we blow up countries and we replace their leaders with leaders who we like. So for any American to accuse us of being violent is extremely hypocritical,” Newsome added….

As the interview concluded, Newsome added, “I just want black liberation, and black sovereignty. By any means necessary.”

My thoughts: By any means necessary? Rioting is not ruled out? The problem with accusing BLM of violence is that it’s merely hypocritical on the part of the accusers? So, one wrong (by others) justifies another wrong (by BLM)? Apparently, two wrongs do make a right—when right is defined as whatever achieves the goals of the BLM organization. I think that helps clear up the interpretive question.

- What should one do if one has been wronged? Instead of engaging in faulty two-wrongs-make-a-right reasoning (and behavior), perhaps the following notion is important: forgiveness.

Hendrik van der Breggen, PhD, retired last year as Associate Professor of Philosophy at Providence University College, Manitoba, Canada. The views he expresses do not always reflect the views of Providence.

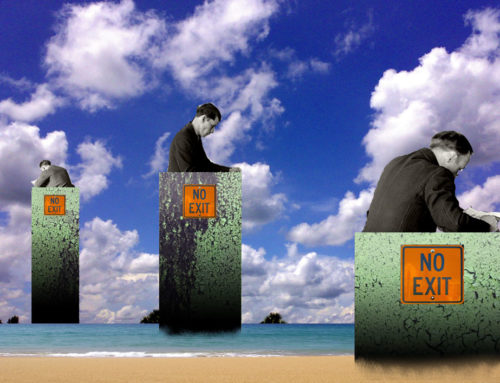

Image: Joukahainen’s revenge, painting by Akseli Gallen-Kallela 1897.

Leave A Comment