By: Dan Corjescu

Recently, while reading Blueprint: The Evolutionary Origins of a Good Society by Nicholas Christakis, I came across an important reminder that “for most of our history as a species, up until about two centuries ago, humans all lived on the edge of death.” This gave me pause for serious thought and reflection.

I thought about how the knowledge of death spurs us on to create, contemplate, and appreciate the things of life more deeply, whether good or bad, beautiful or ugly, noble or base. The knowledge of our impending death, ideally, somehow seems to cause us to burn brighter and more purely during the ever-shortening days of our existence.

I was aware of course that many had pondered the question of immortality before me. Karel Capek, a popular Czech author of the early 20th century, wrote a play, The Makropulos Affair, which was later made into a famous opera by Leos Janacek, depicting a beautiful, talented singer, Elina Makropulos, who having lived over three hundred years—suffered, by her own account, from a life-span that had turned her into an unfeeling, unhappy, and supremely bored creature who nevertheless still feared the finality of death.

Later in the 20th century, the eminent English moral philosopher, Bernard Williams, picked up on this theme in his celebrated article entitled, The Makropulos Case: Reflections on the Tedium of Immortality. As the title of the article suggests, Williams focused on the oppressive sense of boredom that he felt would alight on any denizen of a hypothetical realm of immortality. He wrote that “there is no desirable or significant property which life would have more of, or have more unqualifiedly, if we lasted for ever……Nothing less will do for eternity than something that makes boredom unthinkable.”

Now, as of yet, no one has ever been immortal. So what follows is necessarily speculation, as is admittedly all thought having to do with human immortality. But at present, we can ask ourselves if Williams is right.

To begin to answer our question we might first turn to a philosopher to whom Williams himself refers: the great Spanish thinker, Miguel de Unamuno. For Unamuno, all life wishes to continue as it is. It wishes to remain intact, active, and self-enhancing into the indefinite future. This is Unamuno’s interpretation of Spinoza’s idea of “conatus” to be found in his book The Tragic Sense of Life. Unamuno transforms this Spinozist idea into “un hambre loca de eternidad, de inmortalidad” (a mad hunger for eternity, immortality) which, according to him, firmly inhabits the human breast. A somewhat less extreme, but nevertheless entirely positive view of the desire and benefits of immortality was expressed by the renowned Irish playwright, George Bernard Shaw, in his series of five plays called Back to Methuselah. In these plays, Shaw conveys the idea that the ever growing complexity of civilization necessarily requires longer lifespans and that, perhaps, an important and essential corollary to the ultimate conquest of mortality would be the liberation of mankind from matter itself; culminating in a sort of immaterial apotheosis into impalpable beings composed of energy and light now free to wander the stars. Clearly, the problem of eternal boredom for such creatures never arose within Shaw’s fertile and playful imagination as depicted in these his works.

Another notable thinker on the relative merits and demerits of eternal life is the contemporary philosopher, Thomas Nagel, who in his aptly titled article Death offered a distinct view of the questions now under consideration. For Nagel, “the trouble is that life familiarizes us with the goods of which death deprives us….(and that) death, no matter how inevitable, is an abrupt cancellation of indefinitely extensive possible goods…the fact that we will all inevitably die in a few score years cannot by itself imply that it would not be good to live longer.”

Taking these earlier viewpoints into account as well as some of my own, I cannot initially help but feel that there is something important in the idea that death is an existential spur to life. That it sets a firm boundary to all that is ultimately possible in a human life and perhaps thereby challenges us beyond what we might have initially thought was within our vital circumference of probable time bounded achievements. However with that said, I do not think it at all certain that an infinite life that is accompanied by the prospect of serious technological, philosophical, and moral progress would necessarily be an empty one plagued by a sense of crushing ennui and boredom. Yet, in the extreme case, I think that an eternal life that had the guarantee of freely chosen suicide would adequately safeguard any particular person from being condemned to live eternally. For indeed, if someone were condemned to suffer torture of any kind forever; that would be, I think, commonly agreed to be an undesirable existence and one that was unworthy of continuance.

How long someone can enjoy sunsets, philosophical conversations, food, wine, sex, and long-range space exploration must be left to the individual. Perhaps for some a span of three-hundred years would be sufficient. For others, a thousand. And still others, a million or much more. I think it would be presumptuous of us to speak of how long is too long for a human life to bear. It may be that, in the end, it should be up to each and every individual themselves to decide that. But as I alluded to above, I think the most important right for a potential immortal would be his or her right to end their own existence whenever they felt it to be too much of an existential burden.

Yet there is still something more to say on this subject. Our transient lives are governed by what I would call “mortal time”, an idea stretching its way through Western philosophy from Heraclitus through Socrates to at least Heidegger. It is a time curved to a specific end in death. All our society, culture, and even science is bent by our mortal temporal curvature. Our lives are sorted out and planned according to our inevitable decline and eventual total physical disappearance. The lens through which we view our entire existence is death, our consciousness is therefore a thoroughly mortal one. The songs we sing, the poems we write, the love we express, the deeds we strive for are all conducted through and within “mortal time”. But what would all these things eventually become? What kind of consciousness would arise within us enveloped by “Immortal Time”? What would love, justice, happiness, friendship turn out to be for a human immortal? Surely something quite different than for a short-lived human? Or would it all culminate in an endless gray insufferable boredom as Karel Capek and Bernard Williams wrote about? Or is that, itself, a necessary failure of the imagination of mortal man, a man encased in the awful decay of the flesh and the spiritual extinguishing of the mind and of the spirit? Some suns exist for billions of years, other physical structures for longer than that. What is there to suppose that with a profound physical change in the temporal status of human beings that there would not be a spiritual and intellectual change just as great? How can we, mortal beings that we are, be so sure that “the Tree of Eternal Life” in the fabled Garden of Eden is still to be regarded as poisonous fruit rather than a supreme elixir of as yet undreamed of civilizational possibility and individual self-realization. Immortality may, in the end, not make us gods, but may nevertheless offer us the promise of being more fully human when freed from necessary temporal constraints.

For just as much as types of energy use organizational structures of all kinds, and political and social prejudices can constrain us, so too the temporal chains of death may in the end turn out to have been just one more heavy, unnecessary constraint upon the full expression of the human personality and its innate potential. Immortality, then, may very well reveal itself not as an eternal curse but rather as another milestone in the development of human well-being and thus further cultural, social development. Beyond the other side of time, where time is a choice and not a destiny, may yet lie true human flourishing.

Dan Corjescu teaches Political Philosophy and Globalization at Zeppelin University in Friedrichshafen, Germany

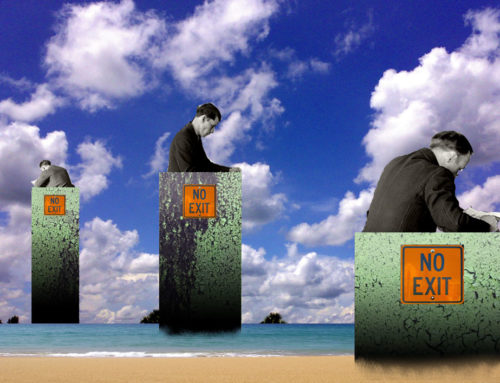

Image: PAM illustration, based on a photo via flickr. (CC BY 2.0)

POLITICAL ANIMAL IS AN OPEN FORUM FOR SMART AND ACCESSIBLE DISCUSSIONS OF ALL THINGS POLITICAL. WHEREVER YOUR BELIEFS LIE ON THE POLITICAL SPECTRUM, THERE IS A PLACE FOR YOU HERE. OUR COMMITMENT IS TO QUALITY, NOT PARTY, AND WE INVITE ALL POLITICAL ANIMALS TO SEIZE THEIR VOICE WITH US.

Leave A Comment