A Meditation on Peace, Justice, and Survival

All goes wrong when, starved for lack of anything good in their own lives, men turn to public affairs hoping to snatch from thence the happiness they hunger for. They set about fighting for power, and this internecine conflict ruins them and their country. —Plato

Man is born free, but he is everywhere in chains. —Jean-Jacques Rousseau

In a time of universal deceit, telling the truth is a revolutionary act. —George Orwell

It is the best of times. It is the worst of times. Never before has humanity been endowed with such fantastic opportunities. Never before has humanity’s survival been so precarious, the threat of self-extinction looming on the near horizon.

To make sense of this ironic situation, and to rectify the issues which now threaten us with majoritarian folly and universal doom, let us return to the most famous parable in Western philosophy: the allegory of the cave in Book 7 of Plato’s Republic. The Republic is Plato’s masterwork on the relationship between education and justice. Plato devotes two-thirds of his enquiry to formulating the kind of education required for a sane, civil and just society.

Via Socrates, the main speaker in The Republic, Plato says: “Society is man writ large.” This is a variation on the notion “microcosm mirrors macrocosm.” Plato’s point is simple. A just society requires justice in the souls of its citizens; or, more precisely: justice in the souls of the “guardians” of society.

The “guardians” are those who conduct the affairs of state. If the guardians are no more enlightened than prisoners in a cave enraptured by shadows on a wall, there is no hope for peace, and no hope for justice, insofar as justice is defined as the well-being of the whole.

Plato begins Book 7 of The Republic with Socrates asking his interlocutor to compare the effects of a proper education with its lack. As the dialogue proceeds, Plato makes it clear that a proper education inspires a pursuit of virtue and wisdom, while a pseudo-education engenders a dehumanizing and perpetual infantilism, in which the falsely educated mistake ignorance and delusion for knowledge and truth.

The latter situation – ubiquitous ignoration – describes contemporary America and large parts of the global community; which is why, despite several centuries of technological and political progress, we find ourselves careening toward ecological and nuclear apocalypse.

Thus, to paraphrase Plato: lack of authentic edification is our most nefarious feature; and a global educational revolution – grounded in ecological reverence and compassionate peacemaking – is our only hope.

But how does Socrates convey to Glaucon, his dialogue partner, the situation I have here described as ignoration? He asks him to imagine prisoners in a large, underground cave, mesmerized by dancing shadows on the cave’s far wall.

Glaucon responds by asserting that the image Socrates evokes is unusual, and that the prisoners are strange indeed. Socrates says: “They are very much like us.”

Plato is describing what existentialists call “the human condition.” We are daily faced with the absurd. To see how and why this is true, let us look more closely at Plato’s allegory, examining its details in order to highlight later the parallels with our national and planetary contradictions. After all, the first step in solving a problem is recognizing that there is one; and though prophets and sages, assassinated statesmen and pacifist activists have long issued warnings about the urgent need for sane and pragmatic reform, their voices have been muted by a perpetual blizzard of epistemological confetti and jingoistic sloganeering aimed at the citizen populace by sophistic politicians and mainstream media technocrats serving the imperial needs of the richest of the rich.

The prisoners in Plato’s cave have been there throughout their lives. Their legs are chained to the floor, and their necks are chained to a wall against which their backs rest. The prisoners cannot stand up and look behind them. They cannot see what is going on behind their backs. All they can do is stare at the cave wall in front of them, across which shadows move back and forth.

The shadows are construed to be the real world, the only world, the enduring dance of meaning and relevance to which they are obliged to give their attention. To pass the time, the prisoners invent guessing games. Honors are granted to those who most accurately predict what the shadows will do next.

Behind and above the wall to which the prisoners are chained, a large fire is kept constantly burning. It is fed by another set of people in the cave, whom Plato likens to puppeteers. The puppeteers carry sticks, at the top of which are carved artifacts. The puppeteers walk back and forth between the fire and the wall to which the prisoners are chained. The artifacts at the top of their sticks cast shadows on the back wall of the cave. These are the shadows which so enthrall and enthuse the prisoners.

The puppeteers, in addition to feeding the fire and casting shadows, talk among themselves. Their voices echo off the surrounding walls of the cave. The prisoners believe these echoes to be the voices of the shadows.

Plato was a prophet. More than two thousand years before the invention of television, Plato imagined a scene in which citizens are deceived into thinking that truth is what they are conditioned to behold and believe.

Plato’s parable has profound contemporary relevance. In what Gore Vidal calls “The United States of Amnesia,” seemingly free citizens are enslaved by what psychiatrist Erich Fromm calls “chains of illusion.”

The puppeteers of the postmodern world are the political, educational and media technocrats who serve the captains of banking and industry whom Karl Marx called “blood-sucking vampires.”

America, like most of the rest of the world, and in many ways even more so, is a high-tech version of Plato’s cave. Self-harming citizens are perpetually fooled into voting against their own best interest.

H. G. Wells noted that “history is more and more a race between education and catastrophe.” The battle for the soul and survival of civilization is now largely a contest between self-harming voters and diminishing prospects for peace and justice.

The tragedy of history is that individual innocence is no protection against collective responsibility. The situation is dire, because we face a trinity from hell: ecological suicide, nuclear holocaust, and another global Great Depression.

Howard Zinn observed: “The truth is so often the opposite of what we are told that we can longer turn our heads around far enough to see it.” Noam Chomsky adds the necessary twist: “The problem is not that people don’t know; it’s that they don’t know they don’t know.” Hence the enduring potency of Marx’s maxim: “The demand to abandon illusions about our condition is a demand to abandon the conditions which require illusion.”

Nationally and globally, the human condition is increasingly scarred by economic apartheid, historical illiteracy, depletion of natural resources, hyper nationalism, scapegoating racism, and the violence of never-ending war.

To ignorate or educate – that is the question. Fromm’s “chains of illusion” constitute an omnipresent web of deception, distortion and distraction: an arsenal of Weapons of Mass Dysfunction, created and sustained by a largely hidden cabal of puppeteers, whose unrelenting fusion of elephantiastical greed, violence and delusion is driving the world toward an apocalyptic cliff.

The puppeteers are not merely the sophists who deceive, distract, and brainwash historically illiterate, self-harming voters by means of ubiquitous advertising and educational, entertainment and news-media systems designed primarily to ignorate. The ultimate puppeteers driving humanity to self-destruction are the mega-wealthy, who own most of the means of communication, whom the visible sophists serve, and who have purchased most of the world’s political systems (to the tragic detriment of democracy and collective well-being). [1]

Michael Parenti makes the crucial point: “The rich are never satisfied. They want it all. If you know that, and nothing else, you still know more than all those people who know everything else, but not that.”

America repeats the unlearned lessons of history. Founded on noble ideals undermined by genocide and slavery, America wraps itself in a cloak of virtue, and ignoring the cautionary wisdom of John Quincy Adams, goes abroad in search of monsters to destroy, not knowing she is destroying herself. Men at the helm of the ship of state, swollen with greed and skilled at sophistry, steer civilization toward the abyss.

Only the blind can fail to see The Statue of Liberty weeping for another lost chance for human history to be something other than ignorance, violence, and ignoble self-betrayal.

With all too few individual exceptions, the difference between the Democratic Party and the Republican Party is the difference between neurotic and psychotic. The prime example is that Democrats have at least occasionally raised the issue of self-inflicted ecological doom, while Republicans continue to label that notion “a liberal hoax” despite overwhelming scientific evidence.

Both political parties resist – indeed, actively oppose – multiparty pluralism, thereby showing their contempt for authentic democracy. This contempt is further manifest in the fact that national holidays include Presidents Day, Memorial Day and Independence Day, while election day remains part of the work week, guaranteeing an absence of many citizens in the voting booth during democracy’s most important hours.

Meanwhile, the mainstream news media, increasingly monopolized and being a primary instrument of collective ignoration, is criminally complicit in the shredding of the Constitution, the evaporation of civil rights, the cheerleading of illegal and immoral wars, and denial-by-omission of economic apartheid and the exponentially intensifying environmental crisis.

Howard Zinn, noting that the problem is not civil disobedience, but, rather, all too pervasive obedience, declared: “Our problem is that people are obedient all over the world, in the face of poverty, starvation, stupidity, war and cruelty. Our problem is that people are obedient while the jails are full of petty thieves, and all the while the grand thieves are running the country.”

Albert Einstein said: “We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.” He said further: “Money only appeals to selfishness and always irresistibly tempts its owner to abuse it. Can anyone imagine Moses, Jesus or Gandhi with the moneybags of Carnegie?” James Thurber once offered the parable of a man standing on his cabin porch watching a forest being cut down to provide timber for the building of an asylum in which to house people driven insane by the cutting down of forests.

The vast majority of American citizens have been conditioned to think that democracy and capitalism are synonymous, and that socialism equals fascism. To which we can apply Mark Twain’s observation: “Loyalty to petrified opinion never yet broke a chain or freed a human soul.” John Lennon said: “I think our society is run by insane people for insane objectives. I think we’re being run by maniacs for maniacal ends. I think they’re all insane. But I am liable to be put away as insane for expressing that. That’s what is insane about it.”

Noam Chomsky notes: “I don’t know what word in the English language – I can’t find one – applies to people who are willing to sacrifice the literal existence of organized human life so they can put a few more dollars into highly stuffed pockets. The word ‘evil’ doesn’t even begin to approach it.” Perhaps two words are needed (with a bow to Mailer and Jung): elephantiastical psychopathology.

Plato says in The Phaedo that “all wars are fought for the acquisition of wealth.” [65c] Today, the American landscape is littered with statues of generals on stallions, while memorials to prophetic peacemakers are barely to be found.

War memorials abound, but where are the institutes for the study and practice of peace that could hold the promise of a better future?

Imperialism is the most potent and nefarious force in human history, and it haunts us today. America has nearly a thousand military bases scattered across the globe, mostly in countries that don’t want them there. New York calls itself “The Empire State;” and the Empire State Building on Fifth Avenue in New York City remains a popular tourist attraction, its very name unrecognized as a paean to the unrelenting violence, death and destruction of mega-wealth’s imperial ambitions.

Decade after decade, American students say history is the most boring subject in school. Perhaps this would change if every history textbook began with Mark Twain’s observation that “America’s flag should be a skull-and-crossbones,” and if parents and students demanded to know why he said that, and teachers were sufficiently well-informed to provide an honest answer.

Accordingly, Victor Wallis, in Red-Green Revolution: The Politics and Technology of Ecosocialism, makes a vital point, then draws the appropriate lesson:

The single most calamitous human impact on the environment is modern warfare …. Militarism, expansionism, and environmental plunder are all of a piece, and find their fullest expression in U.S. policies. An essential task both for environmentalists and for peace activists is to join forces, as the demands of each group reinforce those of the other. [2]

Rachel Bespaloff – who, like Simone Weil, witnessed the horrors of the Second World War and then wrote about The Iliad – says of Greece at the gates of Troy: “brutality threatens civilization.”

As Hegel makes clear, the brute is brutalized by his own brutality. Educated – ignorated – into what Reinhold Niebuhr calls state-instilled “necessary illusions and emotionally potent oversimplifications,” Americans typically miss what Bespaloff calls “the ambiguity of the real.” Alfred North Whitehead – the early 20th century British-American mathematician, logician, metaphysician, and, along with his French contemporary Henri Bergson, the founder of modern “process philosophy” – said: “The recourse to force, however unavoidable, is a disclosure of the failure of civilization.”

Nietzsche, with prescient clarity, foresaw that the 20th century would be the bloodiest in human history. At the dawn of the third millennium, what Nietzsche said of Prussia more than a century ago applies to us as well: “There must be something sick here.” Bespaloff rightly adds that the world of Homer and Tolstoy mirrors our own.

Commenting on the Trojan War, Italian philosopher and mythologist Roberto Calasso notes:

Ajax’s father says to his son: “In battle, fight to win, but to win together with a god.” To which Ajax replies: “Father, with a god on his side, even a nobody can win; but I am sure I can achieve glory even without them.” So Athena intervenes and destroys the hero’s mind …. She is ruthless with those who use her tokens – the sharp eye, the quick mind, deftness of hand, the intelligence that snatches victory – only to forget where they came from.

… Whenever man celebrates his autonomy with preposterous claims and fatal deeds, Athena is insulted. Her punishment is never long in coming, and it is extreme. Today, those who do not recognize her are not insolent heroes such as Ajax but the … numerous “nobodies” Ajax despised. It is they who advance, haughty and blind, polluting the earth they tread. [3]

In her commentary on The Iliad, Bespaloff writes: “The pact between force and fraud is as old as humanity.” Today, the pact between force and fraud threatens all life on earth.

The only sane and civil alternative to global capitalism gone amok is democratic ecosocialism, wherein citizens are keenly attuned to the lessons of history, respect and revere the biosphere, have ample time to continue their self-education, and are well-schooled in the critical thinking skills necessary to detect and refute sophistic speechifying.

A just society is committed to the well-being of all, and is therefore committed to egalitarian economics, universal healthcare, voluntary simplicity, free lifelong educational opportunity, preservation of natural resources, and a modest and well-tamed military overseen by “guardians” committed to peace.

We are free to become free. This is the lesson taught by Socrates. It is also the essence of Buddhism. The word “Buddha” means “awake.” Awakening, as Plato would say, is recollecting the sanity we were born with.

Nietzsche quotes Pindar: “Become who you are.”

We are inextricable strands in the holistic web of being and becoming. Said the poet Byron: “Are not the mountains, waves, and skies, a part of me and of my soul, as I of them?” John Lennon said: “I am the walrus.”

Philosopher George Allan emphasizes the ecosocialist self-evident: “Whoever builds a ladder to the stars, while neglecting the earth beneath, ends by losing both stars and earth.”

A just society values wisdom over mere accumulation of knowledge. Wisdom is the fruit engendered by a Socratic “inward turn.” A refusal to be so enraptured by the outer carnival that we miss the inner festival.

After slaying the Minotaur, Theseus goes to Delos and does the dance of the cranes. On another occasion, Theseus does the dance of the bees, which exhibits the path into and out of the Labyrinth.

The Labyrinth is a picture-palace of the human psyche, at the center of which is the Dionysian impulse, signified by the bull. Minotaur as Freudian id. The untamed reptilian brain. Shadow side of the self, ready to come roaring from the cave.

Nagarjuna, a second century Buddhist sage, said: “When you project all your faults onto me, you are like a man riding a horse who has forgotten where his horse is.” Awakening is facing the Shadow; taming the bull; logos shaping eros into elegant form.

How long, then, before we tame the Minotaur within, creating peace on earth and so bequeath to all children, for all time, the world of opportunity and beauty they deserve?

The battle for lucidity is redeemed in equanimity. What Buddha calls samadhi, Plato calls sophrosyne – tranquility engendered by “a turning about of the eye of the soul.” Toward the light of the sacred hoop of universal brother-sisterhood. Where unity has primacy, and diversity is the spice of life.

Nirvana is not the elimination of desire; it is the education of desire. Not a Thesean slaying of the Minotaur, but a riding of the Dionysian bull into the Apollonian daylight of creative play.

To educate or ignorate – that is question, upon which humanity’s survival now depends.

There is, of course, much in Plato’s Republic we ought rightly reject: secret police, “noble lies,” banishing poets, and dictatorial power in the hands of a ruling elite (be it a Philosopher King, Queen, or Council).

But in addition to being a champion of women’s rights (while still, alas, like Aristotle, too complacently subservient to the preservation of slavery), Plato was right to imply that education is the key to peace and justice, where education is nothing less than what Buddhists would call an enlightenment project.

After the judicial murder of Socrates by a jury too swayed by sophistry, Plato was thoroughly disenchanted with democracy (although, in Book 8 of The Republic, Socrates admits that the just society he envisions – requiring as it does a love of wisdom and philosophic debate – might only be possible in a democratic state founded on the principle of free speech).

Now, whereas Plato is primarily concerned with the education of the “guardians” – deprived of private wealth, their modest needs met by state financing, this being a point worth establishing in the democratic ecosocialism I have here been championing – I urge instead (as the astute reader will have noticed) a commitment to perpetual self-education by the citizen populace as a whole, their curiosity, critical thinking skills, and love of learning instilled at an early age in schools I envision as gardens of self-discovery and creativity, where cooperation has primacy over competition, the virtues and dangers of democracy are daily debated, and kindness, generosity and compassion are prized as keys to authentic self-interest and one’s own highest good.

Buddha anticipates Socrates, asserting time and again: “Life is precious, endowed with freedom and opportunity.”

Plato implies, though he never quite explicitly states, a major theme in both Buddhist and Pythagorean philosophy: The purpose of life is learning and service. Note that learning and service, in addition to voluntary simplicity, are the chief attributes of Plato’s “guardians,” who include politicians, teachers, military and police. To paraphrase Rabbi Heschel: Learning is not merely for life; learning is life. Hence Sophocles – the middle figure in the classical Greek trinity of tragedians – echoes Buddha when he makes this profoundly Socratic assertion: “A man, though wise, should never be ashamed of learning more, and must unbend his mind.”

Unbending the mind – in today’s world, this entails a radical and sincere effort at kenosis: a self-emptying, a purification, an unlearning, which thereby creates space for existentially relevant edification.

As singer-songwriter Paul Simon once wrote: “When I look back on all the crap I learned in high school, it’s a wonder I can think at all.”

Whitehead said: “In order to acquire learning, we must first shake ourselves free of it.”

To shake ourselves free from chains of illusion, William Blake urges a cleansing of “the doors of perception.” This has long been the virtue of Zen; and it is a sign of hope for human survival that the “Mindfulness” movement is today finding widespread resonance in what Marshall McLuhan called “the global village.”

Now, kindly allow me to make three key points. First: I do not mean to imply that all teachers are sophists. Although American students are forced to submit to a compulsory system of miseducation, wherein most teachers merely parrot what they themselves have absorbed – while being forced to force upon their students a persistent ritual of self-destructive test-taking (mere memorization being the lowest step on Plato’s epistemological ladder) – there are, of course, a great many teachers who are well-informed, enlightening, and inspiring.

Second: A major feature of authentic education – in addition to critical thinking skills, historical literacy, and multiple opportunities for actualizing creative potential – is what Richard Rorty calls, echoing the saints and sages of the ages, “a widening of our circle of compassion.” Said Meister Eckhart: “Compassion is where peace and justice kiss.”

Third: For peace and justice to prevail in both America and the world, parents and teachers are obliged to instill in today’s youth a profound sense of global citizenship, wherein the insights of modern science and ecology come together in a daily, acutely felt sense of interbeing. Said Buckminster Fuller: “There are no passengers on spaceship earth; we are all members of the crew.”

Enhancing our chances for a “global mind change,” Victor Wallis, in Red-Green Revolution, notes: “Ecosocialism … has enormous potential to inspire a majoritarian political movement.” [4] He elaborates and qualifies accordingly: “Environmental concern without socialist politics has left the natural as well the human world largely at the mercy of those who are content to treat both as mere factors in their profit projections.” [5]

Our collective survival now at stake, ecosocialism argues that the health and well-being of the whole – biosphere conjoined to demos – must take precedence over private wealth.

Only an ecosocialist politics would have sufficient institutional power to dissolve the injustices of economic apartheid and reverse the depredations of the barons of banking and industry.

What is also needed, therefore, is a twofold educational project. First: a shattering of the illusion that capitalism is synonymous with democracy. Second: a radical dismemberment of the caricature of Marxist politics that has so long reigned supreme in the American psyche, placed there in service to the captains of capital. This twofold educational project entails a dis-identification of socialism with the tyrannies in modern history which speciously appropriated the term to justify their own economic exploitations, ecological pillage, and police-state practices. Note too that capitalism is guilty of these same crimes against humanity and nature.

Wallis declares with appropriately prophetic fervor: “A transformation of revolutionary proportions is the only way out of an otherwise hopeless social and environmental crisis.” [6] Part of his argument is that a crisis can be ongoing and deepening. This is an astute and crucial point. We must place our contemporary national and global predicament – the crucifixion of Mother Earth and the intensifying absurdity of what currently passes for “civilization” – in its broader context. Wallis offers the edifying historical matrix: “It is within [the] general framework of perpetually tightening capitalist domination – over both society and nature – that the history of the last two centuries has unfolded.” [7]

Therefore, “the only way to end class domination is to dissolve the class that dominates. There is no evidence that this class will dissolve itself.” [8]

Wallis’s Red-Green Revolution is a tour de force of lucidity and heart-centered rationality. It echoes the urgency and wisdom of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, Barry Commoner’s Making Peace with the Planet, E. F. Schumacher’s Small is Beautiful, Willis Harman’s Global Mind Change, Howard Zinn’s Declarations of Independence, Noam Chomsky’s Hegemony or Survival, and Naomi Klein’s The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism and This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate.

It behooves us, then, to glance at additional passages from Wallis’s book, partly in order to set the stage for a recollection and completion of Plato’s allegory of the cave and a final meditation on its tragic relevance to our collective alienation from what Plato called The Good, The True, and The Beautiful.

And let us also keep in mind the title of Nietzsche’s Twilight of the Idols.

Wallis says:

Given the limits to markets and resources, … expansionist agendas run into opposition both from rival imperial powers and from anti-colonial resistance movements, creating a scenario of permanent war. [9]

Ecological struggles … are vital not only for the sake of our collective long-term survival but also, more immediately, as offering a unifying theme around which movements representing various specific oppressed constituencies can come together. [10]

Wallis’s book – itself “a meditation on peace, justice and survival,” informed by the medical maxim “do no harm” – thus concludes with an ecosocialist reminder of the urgent need for a revolution in agricultural practices, industrial production, education, wealth distribution, political priorities, and citizen awareness.

Wallis thus also calls for a greater scientific voice in the articulation and diversion of our collective trajectory toward environmental doom.

His book’s last paragraph asserts:

Ecological conversion challenges the entire agenda of capitalist rule. It therefore cannot expect to command universal support.

But it can nonetheless be put forward with the universalistic framing that is customary for scientific exposition. It clearly situates those who advocate “business as usual” in a besieged position. But this is where they belong, as the weight of scientific opinion is against them. [11]

Greta Thunberg is a Swedish teenager. Imbued with ecological despair and courage of conscience, she is leading a global youth revolt against the status quo. As the climate crisis intensifies, the glaciers melt, polar bears die, and the earth burns, she calls on politicians “to act as if your house is on fire.”

Thunberg was recently honored by Tenzin Gyatso, the fourteenth Dalai Lama, as a major world peacemaker and a voice for sanity and virtue.

Wallis echoes the sentiment when he says: “An ethic of service and … the avoidance of waste … [imply] a scenario in which [ecological despoliation, species disappearance, and the climate] crisis itself [stand] at the forefront of everyone’s daily preoccupation.” [12]

Martin Luther King said: “Wealth, poverty, racism, and war – these four always go together.”

Conjoined inextricably to this nefarious quaternity are pervasive sophistry, insidious ignoration, and ecological catastrophe.

Let us now return to the cave parable and complete the story. Plato invites us to imagine that a prisoner is freed from his chains, forced to stand, forced to turn around and face the fire. The fire hurts his eyes. He is dazed and confused. But he is not allowed to return to his seat and participate in the game-show. He is led slowly upward and outward, beyond the cave, to the world outside.

The bright sunlight hurts his eyes, and it takes a long time for him to adjust to this amazing new scene. Slowly but surely, though, he beholds the marvels of nature: a color-splashed phantasmagoria of flowers, bees, trees, streams, ponds, frogs, fish, deer, sheep, serpents, wolves, birds, skies, clouds, moon and stars, and the rhythmic cycles of day and night.

It is as if he has awakened from a dark and dreary, cave-dwelling dream.

He deduces that the sun is the source of all this multifarious life: the blazing energy which sustains the polymorphous splendor to which he is now a privileged witness.

This liberated man – no longer imprisoned and deluded – spends his days in a state of humility and awe, blessed with a feeling of gratitude and grace. All his senses are engaged; his heart swells with new emotions; his mind is a winged and wondrous curiosity.

For the first time in his life he feels free. He feels fully human and whole. And guessing at shadows in a cave, and all the honors therein that might accrue to the best guessers, now strike him as utterly superficial, worthless, and characteristic of a life truly wasted.

But now a new feeling haunts him. What about his comrades in the cave? Can he, in good conscience, leave them to their fate? At first he feels pity; then compassion; then a sense of duty. As much as he dreads the task, he feels obliged to return to the flickering darkness of the cave (what Plato calls the nykterine: “the day that is night”). He feels a duty to inform his friends, and free them if he can; to share with them the path to freedom and awakening.

Plato intends us to understand that the freed prisoner is a symbol for Socrates – that wise, courageous, beloved teacher; Apollo’s messenger, duty-bound to provoke Athenians to “the care and perfection of the soul.”

Plato knows that if we are attuned to such symbolism, we will have a sense of foreboding at this stage of the allegory.

Will the man who returns to the cave to free his friends suffer the same fate that Socrates did?

Plato now invites us to imagine that the Socratic pilgrim beyond the cave – freed from the chains of illusion; basking in sunlight and the freshness of clean air; pregnant with wonder and delight; no longer a victim of the machinations of puppeteers – descends back into the darkness; past the puppeteers and their fire and their shadow-casting stick-figures; to greet at last his comrades and share with them the good news: that a better life awaits them beyond the shadows, games and delusions of their subhuman lives.

What would the prisoners do, faced with this man who has mysteriously returned from the unknown, and who now invites them to a journey of awakening? Plato says they would see him as insane; a confused and nagging fellow; a dangerous disrupter of their game-enthralled comfort zone. And if they could get their hands on him, they would kill him.

The contemporary parallel is stark indeed. John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King, Robert F. Kennedy, John Lennon – the brightest lights of a generation shot out to assure the triumph of the corporate counter-revolution against The Spirit of The Sixties. Giving peace a chance would not be an option.

In his masterwork on Greek mythology, Calasso evokes the politics and praxis of Sparta, thereby allowing us to glimpse our contemporary pathos in what Barbara Tuchman called “a distant mirror” …

It is a grim irony of history that Sparta continues to be associated with the idea of virtue. … They created the image of a virtuous, law-abiding society as a powerful propaganda weapon. … Virtue was nothing more than useful ploy for [hiding] their smug insensibility to the very idea of law. …

Unlike the fools throughout Greece, they knew right from the start that ‘all of them, for their whole lives, must wage perpetual war against every city.’ But the first city they were at war with was their own, … [possessed as they were with] pleonexia, the original sin of lusting for power. …

Sparta underwent a transformation that condensed into just a few years the whole of political history from sacred kingship right through to the regimes of the present day. …

The long transition from sacred king to Politburo was … achieved in one foul swoop. And the fact that this was done while pretending to leave the old institutions intact only added to the audacious modernity of the development. … That was how they exploited their priestly past. It offered a sparkling cloak that protected the secret of politics. [13]

Despite the victory of the mega-wealthy and the war-machines during the tragic course of the last half-century, there is a global undercurrent of awakening that daily increases in momentum.

More and more people are realizing that it is better to swim against the current than to be swept over the cliff.

If philosophy is the journey from the love of wisdom to the wisdom of love, so too is our collective journey to peace, justice, and survival.

Yes, peace is a prerequisite for civil society. But peace is not enough. Justice too must prevail.

A just society – a sane and civil civilization – would institute a program of human rights which guarantees to all citizens: adequate food, shelter, clothing, and medicine; safe and meaningful employment; creative opportunity; and abundant time for community dialogue, arts and festivals, rooted in Gaia-centered reverence.

George Allan offers a definition of Socratic ethics: “Wisdom is pursuit of wisdom. Virtue is pursuit of virtue.” Thus Rachel Bespaloff says the real hero of The Iliad is Hector, “protector of the perishable joys.”

In the Gangamala Jataka – a story of Siddhartha Gautama Shakyamuni Buddha in a previous life – we find: “Nothing lasts. Life is brief. Seek freedom. Be kind.”

Martin Heidegger – despite a tendency to love his Black Forest trees more than his fellow humans – declared with perceptive genius: “Only a god can save us now.” (A line he borrows from the poet Holderlin.) Not a god from on high, descending from some transcendent heaven, but the god within that is the call of conscience: a Socratic voice urging us to free ourselves from chains of illusion and recollect the sanity we were born with.

In sum: world peace through inner peace. Earth as training and play ground for evolving souls. Where the path of awakening is championed as a path with heart.

We are each Hector, obliged to defend the perishable joys.

Stefan Schindler

Stefan Schindler graduated with a B.A. in philosophy from Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Awarded a Woodrow Wilson Fellowship, he received his Ph.D. in philosophy from Boston College in 1975. As Associate Professor in the Humanities Department at Berklee College of Music in Boston, he taught philosophy, psychology, education, and religion from 1976 to 1990. In 1988, he was awarded the Boston Baha’i Peace Award. He lived in a Zen temple in Cambridge for a year; an echo of his three years in Japan as a child. In Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, he taught at The University of Pennsylvania, La Salle University, The University of the Sciences, and Community College of Philadelphia.

Dr. Schindler is a Trustee of The Life Experience School and Peace Abbey Foundation in Millis, Massachusetts. He wrote the Peace Abbey Courage of Conscience Awards for Howard Zinn and John Lennon. With Justice Lewis Randa, he co-founded The National Registry for Conscientious Objection, and co-wrote the Courage of Conscience Awards for Thich Nhat Hanh, Ram Dass, and the Dalai Lama. Schindler’s books include The Tao of Socrates, America’s Indochina Holocaust, Discoursing with the Gods, and Space is Grace. He currently teaches courses at Salem State University’s Lifelong Learning Institute. His forthcoming book is Buddha’s Political Philosophy, an expansion of the same-titled essay which originally appeared here.

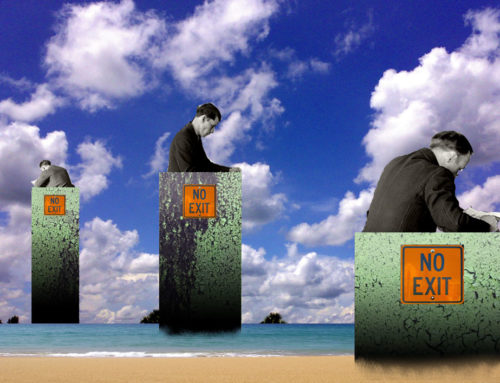

Image: Plato’s Allegory of the Cave by Jan Saenredam, according to Cornelis van Haarlem, 1604, Albertina, Vienna. Via wikipedia

[1] For example, the primary function of the American military (unbeknownst to most American citizens, and resulting in a vast plurality of self-harming voters) is to make the world safe for the depredations and profit of the Fortune 500. Michael Parenti highlights the point when he astutely observes: “Third-world nations are not under-developed. They’re over-exploited.” The history of that exploitation must be well understood for self-harming voters to break the chains of illusion and comprehend America’s tragic repetition of the self-dooming empires of the past. See, for example, my concise, illustrated, student-friendly paperback America’s Indochina Holocaust: The History and Global Matrix of The Vietnam War.

[2] Toronto and Chicago: Political Animal Press; 2018; p. 194.

[3] The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony; translated by Tim Parks; New York: Random House, Inc., 1993; Vintage Books edition: 1994; p. 230-231.

[4] Red-Green Revolution; p. 3.

[5] Ibid.; p. 19-20.

[6] Ibid.; p. 31.

[7] Ibid.; p. 162.

[8] Ibid.; p. 181.

[9] Ibid.; p. 185.

[10] Ibid.; p. 193.

[11] Ibid.; p. 198.

[12] Ibid.; p. 197-198.

[13] The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony; p. 256-263.

Leave A Comment