Journey2Psychology, a project by: Dr. Michael Gordon

Mike Gordon is travelling across the world to converse with influential psychologists and discover the stories behind their work.

This journey will form the basis of a book from Political Animal Press

Follow Dr. Gordon’s travels in full at Journey2Psychology

I’ve had a chance to speak with more than 35 influential psychologists so far on this Journey and there are some themes that seem to be emerging. One idea that has intrigued me, and is echoed time and time again, is the emphasis on being wrong. I can’t put this bluntly enough: almost all of the psychologists I’ve spoken with seem to relish in being wrong. They work to constantly disprove their previous findings, to be the first to find fault in their past theories (and in the directions their field has taken as a result), and to move forward through clearer eyes toward a more perfect truth.

It’s not sadism. There is no strong desire to actually be wrong and certainly they have all labored day after day for research that incorporates better controls, better methods, more foolproof paradigms, and to use population-representation samples. There is no lack of effort from psychologists in attempting to find the truth of their subjects and to communicate that as clearly as they feel is possible. It’s just that, as they reflect back on their own research and findings, they have hindsight which improves their perspective. Moreover, there is a kind of restlessness about those past findings: are they really accurate? What else needs to be considered? What are the weaknesses? Can I make the whole thing fall apart? As the scholar gains in his or her understanding of science, and the field itself changes, the earlier experiments and once-vaunted hypotheses are recast and reinterpreted.

There is a motivation to produce good science and that motivation seems to be integrated with a yearning to understand where one’s past ideas have gone wrong.

In science being wrong might indicate several different things:

1. An unaccounted for variable that influenced the findings without being noticed nor acknowledged.

2. A fluke experiment that produced exciting and unanticipated data that is, unfortunately atypical and does not replicate. See: replication crisis and many labs project.

3. A theory borne of multiple data points across multiple experiments but that has limitations that make it unable to account for new data and/or important emerging ideas.

No one wants to be the scientist who failed to account for critical variables — that’s kind of why the replication crisis is a crisis. We have a deep fear that what we think is deeply false and we jumped to wrong conclusion based on inaccurate findings. CRISIS! For science to progress we need to be able to trust our data; to trust that those studies meaningfully contribute to the larger body of knowledge on which to base theory. No experiment will replicate all the time. There are always weird, odd, unusual, or atypical things that muck with a study and leave it subject to slightly different results every time. Nonetheless, we assume that most studies replicate most of the time because the methods will be well controlled, the participants in the sample are a good representation of the rest of the world, and the analyses were properly executed (thereby providing an indication of the level of confidence we can have in the data). The whole peer review process we go through prior to publishing a study is aimed at evaluating these potential issues, addressing them in advance of dissemination. That some studies do not replicate despite their initial vetting at review certainly creates consternation and slows the progress of the field in the infinite quest for the greater truth of thought and behavior.

All that aside, many influential psychologists set out to disprove themselves and their theories even for extremely replicable experiments and respected ideas. Public acceptance (or at least disciplinary respect) was not the goal of doing the science for most scholars and the motivation to find the wrong and correct it persists even after one’s colleagues embrace an idea as correct.

As a lover of silly sayings and odd quotes two of them come to mind:

The more people that believe it, the more likely it is wrong.

I attribute that particular idea to my childhood friend Reuben Timineri. He…enjoyed skepticism…a…lot. For instance, I’d point out to him that most people believe the world is round. He’d counter that the prevailing view of a round Earth is (a) only recent and (b) that round doesn’t quite cut it. The world is somewhat oblong-spherical and subject to all kinds of forces that may distort that shape over time, subverting the planet’s simplistic categorization as a sphere. Moreover, a sphere is a three-dimensional shape and assumes our acceptance of a somewhat limited three-dimensional universe. Certainly that is a popular idea in current times but it doesn’t necessarily represent the absolute truth. It could be that we exist in more than three dimensions. It could be we have four, five or infinite dimensions and our current limitations only make it seem that the earth is round. It feels correct to say the planet is round or a sphere, but that description is likely incomplete and possibly totally inaccurate. Our friends in physics and philosophy have much in store for us in the coming millennia as our ideas of the universe (and multiverse) expand. So the earth is round. Unless it isn’t. Well-cited, respected studies of human behavior are true. Unless they aren’t.

The point seems to that many of the great scholars I’ve spoken with embrace skepticism. Especially of themselves. First they resist and set out to disprove the major theories of the time (often creating their own sub-field in the process). Then, once they go through the tremendous and decades long process of building a particular theory, then they often set out to change or destroy it entirely. Too often their ideas achieve acceptance just as those originating scientists realize the many flaws in its design. The more everyone else starts to believe in the theory, that is when its progenitor determines that it must be wrong. Science is not about an end-point of truth, but an endless process towards testing, disproving, and discovery.

Another quote — this one much more renowned:

I don’t want to belong to any club that will accept me as a member.

Groucho Marx coined that particular phrase apparently as his reason for resignation from the Friar’s club. Not unlike Groucho, there seems to be a common yearning for iconoclasm among influential psychologists. One might note the irony in that.

The influential psychologists frequently have gained said influence by integrating new ideas, breaking away from the status of the field, and forging new paradigms and embracing divergent, unaccepted cross-disciplinary perspectives. When successful, the result of those hard-won efforts is widespread embrace with prominent publications, major grants and funding of future research, personal awards to the scholars from esteemed organizations, the creation of new journals and venues for discussion of those novel ideas, and, maybe, a legacy in the next generation of scholars with people struggling to better understand and replicate the major ideas in an ever-increasing set of contexts.

In other words, by breaking away from established norms of the field and forging new innovations, the establishment of that field bestows its greatest honors. It may even set forth the creation of new establishments in their shadow. Groucho might have chuckled at that one.

The motivation to be wrong may be necessary to eventually produce something that comes close to right. For the scholars I’ve spoken with, it seems to be working.

Dr. Michael Gordon is a Professor of Psychology at William Paterson University in New Jersey. His research on Sensation & Perception emphasizes auditory and audiovisual detection (e.g., psychomusicology, psychoacoustics, speech, auditory navigation, collision detection, echolocation). He is working on a new project to capture the voices and ideas of prominent and influential Psychologists who have shaped the field. Follow him at Journey2Psychology

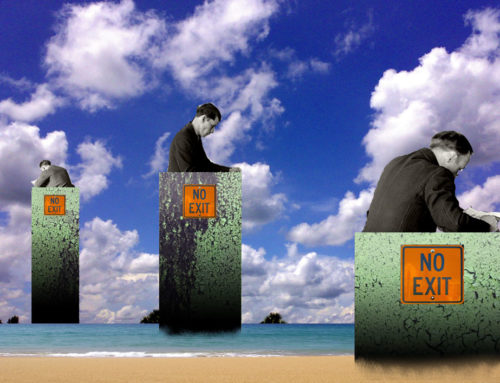

Image: some of the beautiful Rodin statues in the quad at Stanford University

Leave A Comment