By: Brannon Gerling

Can China’s new ‘social credit system’ ethically enlighten its citizens? How would Lao Tzu (6th c. B.C.E.), the central figure in Taoism—that cherished self-exiled sage sapped by the stultifying monotony of the Zhao dynasty—treat all this ado?

Unlike Confucius’s style of virtue-based ethics which rest heavily on the sharpening of moral character, Lao Tzu’s less earthly Taoist ethics individually and transcendentally induce ethical development and hence resist the groupthink requisite for social engineering. The Chinese people’s best means to contest the regime’s new method of domestic persecution lies in their nexus to Tao. They must, as Tzu says in the Tao teh Ching, “hold fast to the original path in order to control the realm of the present.”

The Basics

Many Westerners referring to China’s new social credit system relate it to the dark-humored Black Mirror episode “Nosedive,” and the characters’ angst caused by the manic ritual of social rating isn’t unrealistic. Some of the penalties for an inadequate score will bear similar resemblance to the show: travel restrictions, throttling of Internet speeds, banning (citizens or their children) from choice schools, employment obstruction, difficulty securing loans, and, of course, public shaming.

Who might comply with the story’s credit system or cathartically screw it like the main character does in a mortifying maid-of-honor speech at her pseudo best friend’s wedding? Who really cares?

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) cares and is designing the system with ideal timing: deep learning is wielding big data to digitize everything from genome editing to reconstructions of human thinking. Perhaps the meek or stalwart will be able to ignore the credit system by living inconspicuous or prudent lives, but they will still be scrutinized. A growing network of 200 million CCTV cameras across the public and private domain will use facial recognition, body scanning, geo-tracking and other surveillance tech to track the massive swathe of addicted gamers and screen timers ushered into the largest digitally organised personality heist in history.

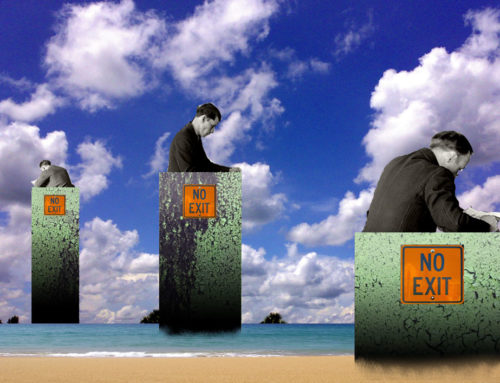

The PRC is mandating a social credit system by 2020 that makes terra nullius feel like ancient history. Through it, the homogenization of a peoples will be automized where Chinese policy has confected an identity complex operating from the world’s largest political nucleus, stolidly programmed to cajole obedient behavior and manufacture consent. It’s another period of the regime game and we’ll see how the red dragon behaves.

Old Methods

One thing we can expect from the PRC: suitable behavior. (One thing that we can expect from ourselves: the expectation that China will exercise predictable behavior.) But we should consider at least two Chinas: historic China and the PRC-CPC (Communist Party of China). China’s old and the old move cautiously, deliberately, in short steps and with a good deal of fuss. The PRC-CPC is a young adult in dynasty years but has gained stentorian proportions. Both will validate each other in their traditions and ambitions, General Secretary Xi Jinping is old and new China ideally manifested, and together the habitual and lusty China will move and make decisions.

Tzu is optimistic about leaders ruling with the unaffected strength of Tao, as Chapter 60 suggests. If politics fuss over and hassle the masses, however, a Taoist realm of peace and sobriety, and the glorious unification China so desperately wants to collectively achieve, will never be realized. Taoist cultivations require individuals to probe the depths of individuation. Furthermore, when populations become politically formed into masses—when they are outlined, systematized, and regimented—the people will be logically incompatible with Tao, because Tao embraces a population of self-possessed individuals, and being Tao-conscious involves the existential exercise of apprehending things through their immediate antitheses, an exercise that is disagreeable to draconian policy seeking monoculture.

It would be senseless to say that the PRC-CPC has some level of Tao-conscious in this regard. What it has inherited is a Taoist style to its procurements, though Tao has no style. It traditionally doesn’t declare war; doesn’t fuss about fame and fortune. It rules its game with ‘carrots and sticks’ and a slow method of accretion called ‘salami slicing’. Yet the bigger the PRC gets over time, the more flagrant are its illegal procurements. The South China Sea might be the best example of regime expansion in the 21st century for spatial and monetary reasons: it encompasses 3.5 million kilometres squared and estimates a few trillion dollars of goods transported through it a year. If the PRC-CPC wants to live on the world stage, it must accept living in the spotlight.

Much of the government’s intentions, however, will fall into the shadows. Like its unremitting propaganda campaign, which bands together the largest population in the world through the puffery of its advertized identity. In general, propaganda machines showcase the intentions of their political systems. In particular, Chinese propaganda works with stigmatic coalescence, whereas American propaganda works with binary fanaticism.

If we were somehow blessed to hear from the ancients, how would they react?

While Aristotle’s and Confucius’s ethical works deliver forms of ‘virtue ethics’, Lao Tzu’s Tao teh Ching throws us a rope to our innermost nature. Five thousand characters of aphorisms flaking cosmically into effervescence, the Tao was born in a cave on the edge of the Zhao regime’s possessive reach. Reading the Tao, we thus quickly gather a smoky flavour of gentle anarchy, which sharply contrasts with Confucian thinking like Plato versus Aristotle. Legendary history says that because Confucius focused on virtue and ritual, which has backed armed law as China’s most collectable, and Machiavellian, domestic resource, Tzu felt that Confucius couldn’t penetrate the infinite understanding and thus excluded himself from reaching the highest state of mindfulness—Tao.

Of course, Tao is a mystical realm of consciousness that most people ignore. It’s spiritually cohesive with what the ancient Greeks called (and Kierkegaard perhaps overthought) telos, the end result—a kind of experiential black hole between the self and eudaemonia—that people long to experience before death. The goal is the same, but as the East has a non-linear way of expressing high ideas, the West uses linear expressions, hence Tao translates to ‘the Way’ and telos to ‘end result’.

Lao Tzu’s Cascade

Austerely terse, the Tao contains a passage in Chapter 38 that can be used expressly to rank China’s new social credit system and other politico-ethical systems, even Confucius’s. Not only does Chapter 38 illustrate the schism between Aristotle’s and Confucius’s virtue ethics and entwines Lao Tzu’s ethics with Spinoza’s and Kierkegaard’s anagogically infused versions, it offers readers a scale of highest to lowest ethics in a poetic cascade of morality. According to John Wu’s translation, it reads:

Failing Tao, man resorts to Virtue.

Failing Virtue, man resorts to humanity.

Failing humanity, man resorts to morality.

Failing morality, man resorts to ceremony.

Now, ceremony is the merest husk of faith and loyalty;

It is the beginning of all confusion and disorder.

We see Tao and Tzu at the purest top of the ethical cascade, Confucius and Aristotle just below with virtue. Plausibly, Buddha’s Eightfold Path exemplifies humanity. Moses’s Ten Commandments morality. Down somewhere in the brackish waters lies China’s social credit system and ceremony, an awkward monomaniacal dance of behavior so remote from conscious intent that it disassociates with ethical practice.

Since Tao is out-of-reach for most people struggling to pay bills and raise families, they resort to other less conscious ways to manifest the good in the paradigms of their actions. Nevertheless, knowing that we can do better—that there are higher levels of cultivation to experience—has always been the impetus for actually doing better.

Further unpacking the passage above, we can compare translations. In Stephen Mitchell’s translation, goodness is used for virtue, morality for humanity, and ritual for ceremony. Mitchell’s moral cascade ends with the lines, “Ritual is the husk of true faith, the beginning of chaos.” Apocalyptic sentiments thus emerge. What kind of ‘confusion’, ‘disorder’, and ‘chaos’ can we expect as a result of ritualizing behavior with the steroidal aid of algorithmic mechanization?

Some Upshots

Algorithms don’t think per se, they hone and choose, and they are indeed furnished with programmer bias. This is the first point here to recognize. The CPC will never create utopia with the help of deep learning; they will, however, lead citizens to believe they are on the utopian bullet train. Secondly, it is constructive to note that no ancient nor modern philosopher has conceived a code of right behavior, nor would they. This is why we should consider Tzu a philosopher and certainly not a prophet. Philosophers design moral ideas within the structure of free holistic man; prophets knot moral ideas to the shattered spine of man fallen.

Besides a heap of generic meretriciousness, we can expect in China what Kierkegaard would wail a social nightmare. On the outside, it would look like traffic as usual, settling even further in its banausic grooves. On the inside, individuals will struggle incessantly towards self-possession and the Taoist yen to return to the nature. How the policy leaders choose to orchestrate this mass of character depends on what it thinks it needs to reinforce its identity, an identity that has wanted to enforce its strength, personality, and cultural rituals since the Korean War.

A renewed kind of anti-government sentiment is intensifying as the world spends more and more isolated time facing screens stewing over being counted. It’s uncertain whether Chinese citizens will be boiled with the frog. Some will play the game well; others will lose out. The consequences will turn human rights into ‘benefits’ rather than a priori foundations of competent government for all. This will eventually request amendments in China that should never have been implemented if ceremony didn’t eclipse Lao Tzu’s higher levels of moral exercise. Though with 1.4 billion people under one flag, and some warranted hysteria to protect itself in the nuclear age, ceremony, the religious theater of the PRC-CPC, will be the choice method to further gather a homogeneous society.

It will all be justified by the bulldozer of utilitarian ethics. Morality can be quantified, albeit awkwardly, as utilitarian Jeremy Bentham attempted (and utilitarian philosophers still allude to) in his ‘hedonistic calculus’, but in practice we individualistically exercise a scalar enterprise of morality that, if we get the chance to look above us, has a limitless Taoist sky.

It is conceivable at least that the PRC-CPC has gathered a decent model template for citizen behavior—it has come from one of the oldest civilisations on Earth. But regimes must be compared to regimes, and they aren’t defined by their systems of morality but rather by their ability to shift the interdistrict ethos according to political desires, desires that power identity enlargement and influence. This isn’t an overall negative thing if net happiness increases, but as the metropolitan honeymoon wears off and the Chinese people long for the breath of space and nature’s therapy, inspired so genuinely by Lao Tzu, more will seek life overseas and break away from overbearing and polluted lifestyles.

One thing’s both historically and immediately evident. Taoism, China’s primogenital exemplar, is incompatible with China’s systems, but deeply twined in the oceans of heart and mind, it may still be China’s only hope for worthy governance. Like one of my Chinese students proposed, citizens could simply ignore the system. Lao Tzu did by abandoning the empire on the back of a buffalo. Though for most certain freedoms will be constricted beyond undetected ignorance. Some things just can’t be ignored, like perfect timing as the digital suffuses reality, and it’s all happening under the iron sky of the most centralized system in the world.

Brannon Gerling teaches humanities at Western Sydney University with an ethical focus.

Leave A Comment