Guillaume LeBlanc from New American Perspective analyzes the highly polarized political climate in the United States.

Among the more striking developments in American politics recently is the increased polarization of the two parties. Republicans have moved to the right, Democrats have moved to the left, and this shift is easy to see. Even the 2008 version of Obama, who opposed gay marriage, talked about immigration restriction, and even said that he could understand nativist sentiment, could not win his party’s nomination today, even though he was hailed at the time as the triumph of its progressive wing. For all the talk of how similar the two parties are, it is actually getting clearer and clearer that there are major differences between the two parties. They may both be terrible, yes – but they are different kinds of terrible.

It wasn’t always like this. For decades, both major political parties in the US were defined by their lack of polarization, which allowed for both parties to have liberal, moderate, and conservative wings. It may be true that since at least Franklin Roosevelt, if not William Jennings Bryant or William McKinley, that the Democratic Party tended to be the more left wing of the two parties, at least on a national level, but this was only slightly true. Ideological diversity was seen in both parties, and it forced both parties to make compromises within themselves, with each faction needing some say in order to keep the peace. And when parties are already making compromises within themselves before they meet the other party, making compromises with the other party becomes much more natural. During this era, party line voting was rare, with liberal Democrats joining liberal Republicans and conservative Democrats joining conservative Republicans on many bills, which is why, though his party only held the majority in the Senate briefly and never held it in the House, Ronald Reagan was able to get so much of his agenda passed-:there was a large number of conservative Democrats willing to work with him.

A major reason why the US was able to achieve this scenario is that, for a very long time, party identification was not based on ideology, but rather on qualities such as ethnicity and religion. Thus, men of differing ideologies would be members of the same party and would have to work together, as political party was a question of old stock vs. new immigrant, Protestant vs. Catholic, Yankee vs. Rebel, and so on, and not just left vs. right. During this time in the North, people from the old stock (pre-1870) overwhelmingly voted Republican, allowing for men like Nelson Rockefeller, considered to be the textbook example of a liberal Republican, and Howard Buffett, a man so hardline in his opposition to the New Deal he would later correspond with and earn the praise of Murray Rothbard, to share the same party. Likewise, in the North, those from new immigrant descent (post-1870) tended to favor the Democrats, allowing for men like Mario Cuomo, who helped to popularize the “personally opposed, but…” line for Catholics on abortion, and Bob Casey Sr., who was sued by Planned Parenthood for the abortion restrictions he implemented as governor of Pennsylvania, to share a party — they were both, after all, sons of new immigrants. So important was this pre-1870/post-1870 divide in the Northeast that it was actually fairly common up until the early 1990s to see a race between a pro-life Democrat and a pro-choice Republican (see the 1990 Pennsylvania gubernatorial election). If you were of the pre-1870 stock and thus a Republican, you were likely a mainline Protestant, a group which has historically supported abortion rights. But if you were of post-1870 stock, and thus a Democrat, you were also very likely to be a Catholic ,whose religion teaches strong opposition to abortion.

Likewise, while it is commonly thought, and for good reason, that the overwhelming support for the Democratic Party seen in Dixie during this time had a rightward impact on the party, it is important to remember that here almost all elected officials were Democrats regardless of their ideology and thus included diverse factions. These included anti-New Deal race baiting populism (Eugene Talmage from Georgia), pro-New Deal racist populism (Alabama’s George Wallace and the even more extreme Theodore Bilbo from Mississippi), landed aristocrats whose racism tended to be more paternalistic than vitriolic and Negrophobic (the Byrd family from Virginia), and even those who had surprisingly progressive views on race for the time (Big Jim Folsom from Alabama and his protégé George Wallace during his younger years). And even more telling, it is important to remember that thanks to Jim Crow disenfranchising black voters, the Republican Party in Dixie tended not to be restricted to the liberals, but rather those from the areas – namely the mountains – that opposed secession during the Civil War.

Today, ethnicity and religion has given way to pure and naked ideology in party identification. No more does one’s religious denomination matter; rather, it is religiosity in general, with the most religious voters voting Republican and the least religious voters voting Democrat, as religiosity is now an indicator of ideology. No more does the old stock/new immigrant distinction matter, with liberal Irish-Americans and liberals of English heritage voting Democrat, while each of their conservative brethren votes Republican. No longer does the old divisionsof the Civil War matter either. Alabama liberals may be a minority in the state, but now they vote alongside their liberal Vermont counterparts, while the minority of Vermont conservatives vote Republican along with Alabama conservatives. Even class distinctions, though certainly more important than what someone like Thomas Frank likes to indicate, have weakened in terms of party identification. In every presidential election from 1948 until 1980, with the one exception of the 1964 landslide, wealthy, socially liberal Marin County, CA voted Republican alongside its wealthy, socially conservative neighbor to the south, Orange County. Today Marin County has joined several other counties around the nation where wealth and extreme Democratic voting patterns exist side by side.

1992 is a key year to understanding how we got here. First, a bit of background information: part of the reason we were able to see huge Republican victories from 1968-1988 is because Nixon, and later Reagan, were excellent at using anger at the cultural upheaval of the 1960s to snatch up former Democratic voters while more or less keeping the old Republican coalition in line. And in 1992, the Democrats were in a pickle. They had lost 5 of the past 6 presidential elections. In four of these losses, their nominee won 10 or fewer states, and in two of these losses, the nominee only won one state. And their one victory came right after Watergate – and was still close. It looked as if the Republican Party was, at least on a presidential level, an unstoppable juggernaut that would dominate politics for years to come. But something was happening behind the scenes. Though liberal and moderate Republicans, for the most part suburbanites in the Northeast and West Coast, had been loyal to the GOP throughout the 1980s, they were becoming increasingly unhappy with the new rightward GOP. Enter Bill Clinton, who offered them a deal: vote for me and I’ll give you the business-friendly economic policies you vote Republican for, while also shoring up support for gay rights and abortion. And it worked, for only the second time in history and first time in a close election: the GOP was shut out of the Northeast and also lost all three West Coast states. The GOP has only managed to win a state in the Northeast twice since: New Hampshire in 2000, and Pennsylvania in 2016 – and has not managed to win one West Coast state.

But for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction, so following this, George Bush in 2000 was able to win in part by snatching the remaining socially conservative Democrats in places like north Alabama, West Virginia, and western Pennsylvania, who were growing tired of the party’s new hardline stance on social issues. And indeed, 2000 would see the GOP make huge gains with these voters. For the first time in a close election, the Democrat was shut out of all of the former Confederacy, while Bush also picked up West Virginia to boot, a state that was not considered competitive and whose electoral votes would have given Gore the election. These two elections essentially set us on the path of no return towards polarization. The huge losses liberal Republicans took in 2006 and conservative Democrats took in 2010 were the icing on the cake.

1992 also saw two key events at both parties’ conventions. It was in that year Bob Casey Sr., the staunchly pro-life Democrat governor of Pennsylvania, was forbidden from giving a pro-life speech as part of the minority plank (something parties did historically to keep the peace) at his party’s convention, while the socially liberal Republican governor of Massachusetts William Weld (yes, that William Weld) was booed at his party’s convention for giving a pro-choice speech. It was at that point that it became clear that the Democrats were going to be significantly less tolerant of social conservatives within their ranks and Republicans were going to be significantly less tolerant of social liberals within their ranks. The fact that Pat Buchanan even had to threaten to run third party in 1996 should Bob Dole pick a pro-choice running mate sounds like science-fiction today. Any Republican who even thought of doing that today would risk a full-on revolt (which is why John McCain did not choose Joe Lieberman in 2008). As another example of how the parties used to function, George McGovern is often held up as the ultimate example of the left flank of the Democrat Party getting what they want, and despite his status as the candidate of “amnesty, acid, and abortion” the unassuming South Dakota son of Republican parents picked not one, but two pro-life Vice-Presidential nominees. Any Democrat who would do that today would run the risk of being crucified by the base.

All this leads to the question of what can be done to combat increased polarization, and the answer is: very little. The old ethnic divisions of the past that at one time kept polarization at bay are gone, and are not coming back. It is also important to remember that much of what informed the ethnic voting patterns of the 20th century was built more on a distrust of the other party than any deep love for the party one actually belonged to. What are we supposed to do? Convince the staunchly pro-life Catholic voter to vote Democratic because some random WASP Republicans at a random country club 100 years ago thought her ancestors were “wops”? Or perhaps we can convince the socially liberal, irreligious voter to vote Republican since his ancestors feared the “party of rum, Romanism, and rebellion”? What about the farmer in south Alabama who is passionate about the 2nd Amendment? Can he be convinced to vote for Democrats since Republicans burned down his ancestors’ homes? Black Americans are something of the Gibraltar when it comes to this, as even religious, wealthy, conservative black people will often still be Democratic, but it is important to remember that black people are unique in American history thanks to the legacy of slavery, so it is unlikely that this will remain anything more than an outlier, a reminder of how political parties used to function.

Ending the modern primary system and going back to the days when the party elites would pick candidates, as is still the case in Canada and Europe, could work, as it would prevent people like Roy Moore from winning any nomination, but this has little chance to pass, and any attempt to do so would likely only inflame passions even more and result in even greater polarization. The Democrats have their superdelegates as a way to prevent another McGovern-style disaster at the presidential level, but this too will likely either be gone or severely weakened by 2020, thanks to the influence of the Sanders bloc.

Smaller things can be done that may or may not be able to put the brakes on polarization, however. And on this point, it is important for both parties to remember that though polarization is real, it is not the case that every Democrat is a communist and every Republican is a fascist. Actual communists and fascists are people on the margins of American political life, and election losses need to be greeted with an attitude of “Well that was disappointing, but I’ll live” rather than acting like prison camps for thought crimes are right around the corner. It is also important to remember that being fired is a serious offense and that both the left and the right are guilty of launching witch hunts to get people fired. Yes, it is true that legally speaking, the First Amendment only applies to the government, but freedom of speech is far too important to recuse to this narrow legalism. Free speech must be a cultural value in addition to a legal one, and corporate power can be just as corrosive as government power. The threat of joblessness and poverty is very serious, so everyone must think long and hard before trying to get someone fired.

Furthermore, both sides must remember to keep their eye on the ball and not try to take a mile every time they are given an inch, as this leads to backlash and thus more polarization. Most Americans are willing to take feminists’ concerns about how rape and sexual harassment are treated in society seriously, for instance, especially after high profile cases (i.e. Steubenville or Harvey Weinstein). What they are not willing to go is expand the definition of rape to include anything a woman decides to call rape, and they certainly are not willing to shift the burden of proof away from the prosecutor or do away with the presumption of innocence. Likewise, most Americans are willing to consider increased immigration restrictions, but what they are not willing to do is embrace draconian measures like mass deportation or a wall between Mexico and the US.

For the foreseeable future, the Republican Party will be the party of conservatives, regardless of their ethnic and religious background, and the Democratic Party will remain the same for liberals. The days of the WASPs versus “rum, Romanism, and rebellion” are over, and we will have to make do with what we have. Polarization is here to stay — but there are steps, though small and mostly on a personal level, that can be taken to alleviate some of its more corrosive effects.

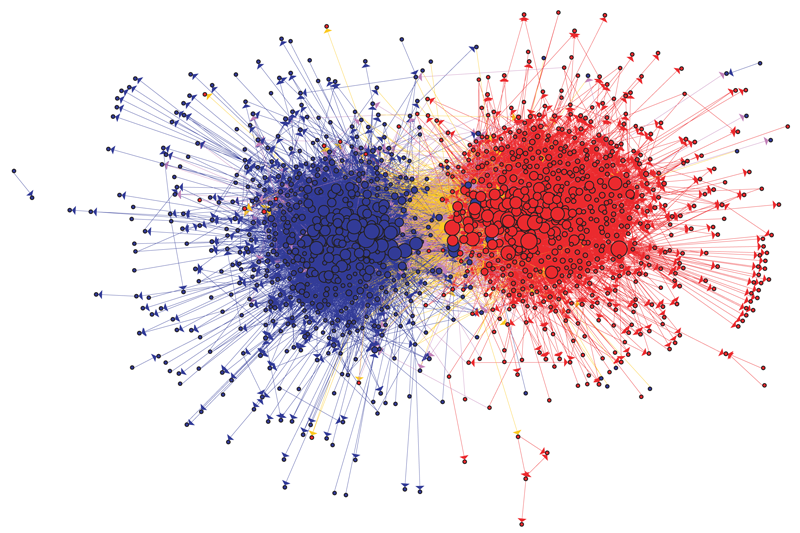

Image: Lada Adamic’s famous visual of Democrat and Republican blogs during the 2004 US electionc (CC BY 2.0)

Leave A Comment