By: Glen Paul Hammond

The first effect of not believing in God is to believe in anything.G.K. Chesterton

Sonia Maria Pavel, in her recent article on Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France, examines the way the 18th century Irish statesman, author, political theorist and philosopher, expressed concern for the dismantling of the old decent draperies of life by what he saw as the “new conquering empire of light and reason” (Pavel). Pavel’s article focuses on two dimensions of Burke’s argument: The first is his historical and anthropological account of both the origin and function of “pleasing illusions” within a culture, and the second is his justification for the intentional revival of those illusions, which he saw as necessary for the establishment of social cohesion. Pavel’s two-dimensional perspective is offered as a lens for the examination of political deception and what Burke saw as the instrumental value in having a politically beneficial fiction. In my view, however, this approach also serves to highlight a part of Burke’s argument that is most necessarily applicable for the maintenance of free societies today, and one that Pavel does not address in her article. Namely, that human beings are religious animals by their constitution and that, in the case of the West, without the Christian religion there would be a void left in the minds of people that would soon be filled by some other more pernicious superstition. Ultimately, this would undermine the existence of Western liberal democracy (Burke 75). Recently, this opinion has even been reasserted by the most unlikely of sources: the intellectual atheist, Richard Dawkins.

According to Pavel, Burke defended the necessity of prejudices, and the conventions that they generate, as a means to produce “a common moral heritage that engendered stability through feeling of familiarity and belonging.” She argues that such pleasing illusions “surrounding power” were “not designed as ways of deceiving people into obeying authority,” but rather evolved alongside a mechanism of mutual obligation that produced a societal system of functional requisites. Through an investment in the requisites of the community, a cultural ethos was produced that was gentler and more liberal than any system could be if the same behaviors were enacted through a set of laws, enforced by an authoritarian agency. Prejudices such as these, which evolved not through calculated planning for any particular end, but rather “emerge and develop historically,” provided individuals with a means to negotiate the world that, in their absence, would leave members of a society “alone and afraid” with nothing but what Burke called their “naked shivering nature” (Pavel).

The “pleasing illusions” of Burke, focused on a “gradation of social life”(Burke 64) that followed a divine order or Great Chain of Being that placed God at the top of a stratified system of monarchy, which, in turn, produced an apparatus of obligations that became the bedrock of a “common moral heritage”(Pavel). Since, as both Burke and Chesterton argued, God fulfills a human need to believe in something larger than the self and, without it, the void would be filled by some other ideology, the atheist Richard Dawkins has recently suggested that the benefits of educating people about the Bible may serve to establish something similar to the familiarity of belonging that Burke articulated in his Reflections (Carter). In essence, the author of The God Delusion is asserting that Cultural Anglicanism provides a desperately needed basis for social cohesion.

Considering Anglicanism to be superior to “the competition” (Murray), Dawkins rejects the idea of cultural equivalence and states that the Church of England espouses “a cultural heritage that is beautiful, coherent and benignly tolerant” (West). Citing a historical example, in a recent interview with Ed West, Dawkins recalls how lucky Charles Darwin was to be able to present “his ideas to an Anglican society,” adding that “a scientist who upset the world view of today’s cultural leaders would find things much harder.”

Just as with Burke’s remonstrance that the social benefits of “the moral imagination” outweighed any consideration of its facticity (Burke 64), Dawkins argues that believing in the “truth” of a religion is not so important as having it, since, he states, the Anglican tradition helped create the liberal societies that uphold liberal values (West). “I sort of suspect,” he tells Douglas Murray of The Spectator, “that many who profess Anglicanism probably don’t believe any of it at all in any case but vaguely enjoy [it], as I do…. I suppose I’m a cultural Anglican and I see even song in a country church through much the same eyes as I see a village cricket match on the village green.” Similar to Burke’s argument that the “elevated sphere” of a monarch provides the institution and laws he represents with the admiration, respect and awe the monarch inspires, Dawkins suggests that the moral capital of Anglicanism is where its social value is to be found.

In Britain, as in many Commonwealth nations, Anglicanism is an already established part of the national story and character. The framework of constitutional monarchy and a still extant nostalgia for Anglicanism provides both a means and motivation for its virtues to be passed on to future generations. The Church of England is still, for example, the Church of England, and Queen Elizabeth II, is both the supreme governor of this church as well as the symbolic head of state.

Utilizing this national heritage in countries willing to assert Burke’s cultural prejudice, would ensure that such conventions and liberal “sentiments which beautify and soften private society” (Burke 64), remain incorporated into both the ethos and the political framework of the working cultures that employ it. As such, theorists like Dawkins see no conflict of interest in giving Anglicanism special status in the free societies of the Commonwealth. This is not only due to the symbolic position the Queen holds as the chief power of the realm in both Ecclesiastical and Civil estates, but also a result of what Dawkins calls a kind of literary justification for studying the King James Bible in the same culture from which that piece of literature originated.

For Burke, the key mechanism in the edifice of society resided in that society embracing a particular perception of the world as being superior to others. This, of course, challenges the post-modernist narrative of multiculturalism, which asserts that any notion of one cultural idea being superior to another smacks of either ethnocentricity or some form of racial prejudice. Forgoing the obvious rebuttal that criticism of an idea, even one rooted in culture, is, in and of itself, not indicative of racism, a more helpful response to the post-modernist view can be found in Burke’s own understanding of what forms a national character; namely, that “communities and cultures are not built from scratch in accordance to a rational plan to yield particular results, but emerge and develop historically” (Pavel). As a result, an idea that works for one culture may not, necessarily, work for another, because distinct societies have, over time, generated support systems that allow their collective visions to function through an historical evolution where ancient principles are passed down from generation to generation (Burke 63). Yet, Burke warns, the ancient principles cannot survive the subversion of the ancient institutions that support them; both ensure the existence of the other (Burke 65). Thus, in the absence of the prejudice that operates alongside the institutional practice, or vice versa, the collective vision disintegrates and the framework ceases to function.

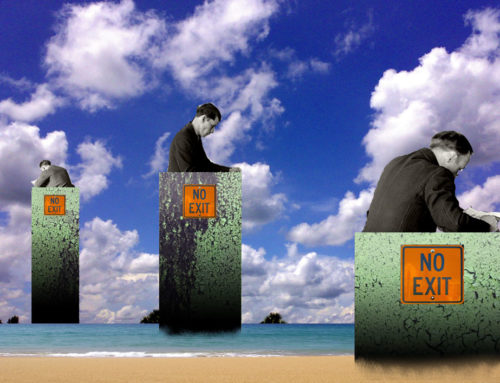

This is the main reason that atheists like Dawkins are beginning to realize the necessity of religion as a pleasing illusion. It fills a void that the former British Prime Minister, David Cameron, identified when he admitted to the failure of state multiculturalism “to provide a vision of society” (Taylor). This failure, Cameron said, provided a breeding ground for the radicalization of individuals who were made to feel rootless in a society that had no other culture to which they could belong (Taylor). It can be argued, then, that the failure of multiculturalism resides in the failure of post-modernist sensibilities, which seek to eradicate prejudice only to leave naked and shivering individuals standing alone and afraid in its wake.

Seen in this light, Cameron’s espousal of “muscular liberalism,” may best be served by the Cultural Anglicanism that, Ed West says, provides a kind of remedy for the “train wreck of multiculturalism.” Platitudes of tolerance and fairness, “are vague and meaningless,” according to West in his interview with Dawkins, the only other option is totalitarian—“respect difference, or else!”

This is mirrored by Douglas Murray, another intellectual atheist, who argues that the fatal flaw in the European Union’s (EU) constitution and its “human rights” program, which relies entirely on high-flown rhetoric alone, is that it does not acknowledge the thrust of its desire for human rights comes from the sensibilities of Europe’s Christian past (Tucker). For Murray, the death of Europe is rooted in its loss of identity, an identity that can only be promoted in the foundational ideas that individuals share and pass on in their “unifying stories” (Tucker).

In Burke’s view, the mystique that surrounded majesty, and the stratified system it supported, was not the deceptive mechanism of a ruling class, but the result of a common worldview that made the beautifully decorated trappings of monarchy a natural manifestation of a pleasing illusion embedded in the culture. This pleasing illusion or prejudice inspired the functional requisites that generated a mutual obligation to “power and privilege” (Pavel). By this same logic, according to Pavel, Burke argued that the “sumptuous and awe-inspiring” decorations of churches and cathedrals did not serve a deceptive function or even produce the prejudice that supported such outward displays of the institution’s importance, but rather the trappings of the church and the prejudice that inspired it served a mutually beneficial function that evolved, interdependently, over generations.

A civil society, according to Burke, is made for the advantage of the individual, who, as part of that society, has an equal right to its benefits. This institution of beneficence creates laws that are, themselves, the beneficence of the rules that society espouses. In this way, the civil social individual is the product of civil society and civil society is the “offspring of convention,” which, in turn, gives root to the legislative, judicial and executory power that ensures the rights that each individual claims to his own benefit (Burke 50).

Promoting Anglicanism at its tolerant best, in this way, generates the sensibilities it espouses, and strengthens the edifice that fosters its common purpose. This, then, ensures that the inclusivity of immigration programs, such as Britain’s, remains stable enough to function. Such a cultural prejudice allows the culture itself to be offered to and enjoyed by others. The pleasing illusion that must surround this power, however, is best derived from the conventions and religious heritage that created it. It is, according to Dawkins, an Englishness and an Anglicanism that can best be found “in the King James Bible and the complete works of Shakespeare,” the rest, he says, “is just commentary” (West).

Glen Paul Hammond has a Master of Arts in English Literature from the University of Toronto. His publication credits include the educational book, The Literary Detective, and a forthcoming collection of short stories, entitled, Even the Moon is Frightened of Me, from Political Animal’s sister imprint, Crowsnest Books. Satirical cartoons and more of his writing can be found on his blog, SCRATCH.

Leave A Comment