By: Glen Paul Hammond

“Come, you spirits that tend on mortal thoughts, unsex me here, and fill me, from the crown to toe, top-full of direst cruelty!”

With these words from William Shakespeare’s Macbeth, the playwright provides modern readers with a sense of what the western world’s view of womankind was in the late medieval period. This view backed up a foundational belief that women were ill-suited to the hard demands of leadership outside the home. Shakespeare’s stratified society was a more complicated system than our own; aristocrats were “born to rule,” and women, depending on their placement within that system, were, more or less, expected to turn their talents to the personal sphere of society, allowing men to apply theirs to the professional world that operated outside the home. In Lady Macbeth’s desire to “unsex” herself, the character outlines the way different traits were assigned to the sexes: She wants kindness to be replaced with cruelty, and compassion to be replaced with action.

As these caricatures of sex traits began to be dismantled in the post-feminist world of the 20th century, female leaders were expected to adopt the attributes of male-styled leadership, since these were still considered the defining features of a leader. However, by the end of the 20th century this began to change, so much so that in the early 21st century, the pendulum seems to have swung the other way.

Before an examination of this can occur, however, it is necessary to gain some sense of the historical underpinnings.

Even a quick investigation into England’s Tudor period will verify that Shakespeare provided an accurate representation of the way Western culture viewed the personality differences between men and women. Mary Villeponteaux, in her treatise on Edmund Spenser’s Faerie Queene, states that women were seen as emotional and “passionate creatures prone to pity” and says that even though Elizabeth I was “praised for her godlike mercy” she was also “accused of excessive lenity”(163). Pity was viewed as a characteristic deeply rooted in the weak nature of women and Elizabeth’s famous speech at Tilbury demonstrates that, at least publicly, she too was willing to accept a similar distinction between the sexes. Facing her troops, on the eve of battle, Elizabeth acknowledged her unsuitability for the martial task at hand by saying “I know I have the body but of a weak and feeble woman,” and then, like any good persuasive arguer, stated the real point she wished to make, “but I have the heart and stomach of a king” (British).

This emphasis on the masculine, as an essential tool of good leadership, has historically been viewed in a positive light. In 1962, before the political fallout of the Vietnam War, the Cuban Missile crisis highlighted this sensibility. At the time, there was a feeling that the young U.S. President, John F. Kennedy, was ill-suited to cold-war politics. It was feared that he did not have the strength to stand up to the Soviets and that this perceived weakness would be a liability in the ongoing conflict between the two superpowers. The showdown with Khrushchev, which involved the risk of all out nuclear warfare, proved critics wrong. Kennedy took an unflinching, confrontational stance that was, upon the successful and peaceful conclusion of the conflict, celebrated as a show of strength.

Second-wave feminism, in part, sought to eliminate the idea that such leadership characteristics were the sole domain of men and worked to avoid its overreaching stereotype by advocating the idea that diversity within a group is greater than diversity between groups. As such, the feminist movement encouraged an emphasis on individual characteristics as the defining features of a person rather than their biological sex or any other superficial, immutable trait. From this vantage point, it can be seen that the hawkish Margaret Thatcher had more in common with Winston Churchill in her defining characteristics as a political leader than, say, the current prime minister of Canada, Justin Trudeau, regardless of their biological sex.

The increased identity politics of a post-modernist age, however, is producing a narrative that makes the individual less important than the identity group to which public opinion says that individual belongs. As a symptom of this, the modern world is adopting a more historical view on gender. Just like Lady Macbeth, individuals now seem able to identify personality traits that sex or unsex them and, though it might seem contradictory, this serves to validate an idea that that there are masculine and feminine qualities. This time around, however, one major difference exists: Today, feminine qualities are viewed as superior.

The public is told that masculinity is toxic and so the traits associated with masculinity are also toxic. It follows then that the leaders the public are encouraged to select will exhibit more feminine qualities and the individuals who wish to be elected will seek to minimize what might be viewed as masculine and maximize what will be perceived as more characteristically feminine. The utter frequency with which Canada’s Prime Minister, Justin Trudeau, publicly breaks into weepy-eyed tears provides a perfect example.

In modern times, the feminine qualities described above have been repackaged as agreeableness, one of the big five personality traits. This personality dimension “includes attributes such as trust, altruism, kindness, and affection” (Cherry). Individuals who score higher in this dimension are more likely to avoid conflict; “they seek to pacify and appease others,” and are more willing “to help others during times of need” (Five). Woman score higher on this dimension than men, who, in turn, score higher in levels of assertiveness.

Men scoring higher on assertiveness, however, is problematic. As modern day Emotional Intelligence (EQ) tests describe it, the willingness of assertive individuals to communicate their beliefs and thoughts openly and to defend their personal rights and values, can also be viewed, from a big trait perspective, as indicative of individuals who score low in agreeableness and are, therefore, “more argumentative” (psych). According to Dr. Jordan Peterson, in an online critique of EQ, disagreeable people “on average make better managers” because, unlike agreeable people who “can also be pushovers,” disagreeable people “are straightforward, don’t avoid conflict and cannot be easily manipulated.”

From this, then, the following supposition can be made: Since traditional masculine traits correspond to the modern perception of assertiveness and, contrarily, feminine traits are more closely aligned with agreeableness, a major shift in the perception of what qualities are best suited for political leadership is revealed. Just as the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 provides an illustration of the prominent role that the trait of assertiveness played in the political framework of the past, an event that occurred in July of 2015, likewise, demonstrates a shift in the perception of what is essential in the present-day political toolkit of leadership: Agreeableness.

The Boston Globe relates that “On German television in July 2015, [Angela] Merkel had reduced a young Palestinian refugee to tears by explaining that her family might have to face deportation” (Ferguson). The article’s writer, Niall Ferguson, goes on to say that Merkel stated to the girl:

“There are thousands and thousands of people in Palestinian refugee camps… If we now say, ‘You can all come’… we just cannot manage that.” The [girl’s] waterworks worked. Six weeks later, Merkel opened the gates of Germany and declared: “We can manage that.”

Ferguson follows this with speculation as to what may have prompted Merkel’s “epoch-making change of mind.” He says, “all kinds of historical explanations have been offered,” including Merkel’s East German upbringing as well as her clergyman father; then Ferguson remarks “faced with Reem Sahwil’s tears, the chancellor’s reaction was an impulsive attempt to comfort her, followed by a massive, unilateral U-turn” (Ferguson).

Elizabethan observers, on the other hand, would have been pointed in their reasoning as to what had occurred. Edmund Spenser, for example, would have had no doubts. Speaking of Elizabeth I, he stated, “by mercy she hath taken more harm than by justice,” and sixteenth century political theorists, such as Elyot in The Gouernour, would have explained that Merkel’s compassion was void of reason and degenerated into a kind of “vain pity,” that the philosopher Lipsius described as “effeminateness, and lenity, and vice rather than virtue” (Villeponteaux 165). Such feminine weakness was what Lady Macbeth feared in her “compunctious visitings of nature,” a nature that the seventeenth century philosopher Thomas Wright said was “more inclined to mercy and pity than men” and so more vulnerable to manipulation (Villeponteaux 164).

A recent Maclean’s article by Andrew MacDougall, ironically titled “Justin Trudeau is between a rock and a heart place on immigration,” strikes a similar tone when examining the quandary faced by the Canadian prime minister’s stated open border policy and the reality of “illegal” border crossings at the Canadian border.

In January of 2017, Trudeau’s compassionate nature was signaled to the world when he responded to President Donald Trump’s first attempt at a Muslim ban. The Canadian prime minister tweeted: “To those fleeing persecution, terror and war, Canadians will welcome you” (MacDougall). International fanfare followed; yet, Trudeau, unwittingly, created an influx of illegal border crossings from the United States that MacDougall describes as having the potential of becoming “a miniature version of what plagued continental Europe.” In order to stop a recurrence in 2018 of what The Immigration and Refugee Board has called an “unsustainable” rise of asylum seekers through the U.S. border, MacDougall says, Trudeau must drop his emphasis on “niceness.”

Yet, considering the zeitgeist of the current political age, is this likely? Just as Merkel’s decision to open Germany’s borders resulted in her becoming Life’s person of the year for 2015, the compassionate Canadian leader would lose his appeal to similar popular publications like Vanity Fair, Esquire and Rolling Stone. As this will undermine his voting base, it is unlikely that he will do anything to make himself appear less compassionate. But at what cost to the national interest? Sounding more like a sixteenth-century political analyst then a modern day observer, Andrew MacDougall warns the prime minister that, before it is too late, he must put “head before heart.”

Both common sense and statistical data suggest that there is more diversity within groups than there are between groups. Medieval rule, at its best, often sought to incorporate both qualities of agreeableness and assertiveness in their decision making process. In her article for The Atlantic, Katrin Sjursen states that noble wives “in the Middle Ages were regarded as co-rulers of territory, alongside their husbands” and “medieval noblewomen had the opportunity to develop a personal ruling style” that incorporated multiple personality dimensions and traits that went far beyond any stereotypically imposed identity group (Sjursen). According to Sjursen, ruling women, like Queen Philippa of Hainault, exhibited both aggressive and conciliatory actions as the situation required. Male rulers, on the other hand, who were more limited in what traits they could exhibit, often relied on noble wives to publicly petition them to grant clemency to a prisoner docketed for execution.

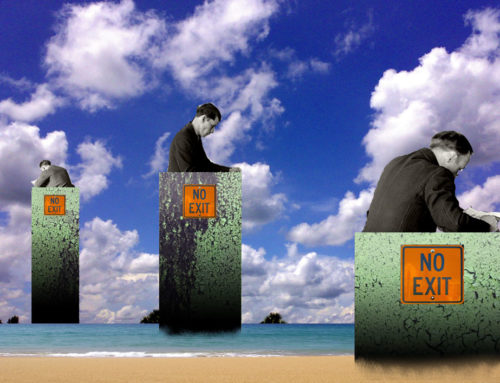

The danger is, then, that as society regresses into the narrow boundaries of identity groups and politics, leaders may feel pressure to remove from their decision making process any assertiveness that might be viewed as too masculine. In this way, the desire to gain votes by being more socially acceptable, will produce a political class that only embraces leadership traits that are not diverse enough to meet the demands of their positions. This, to a certain extent, has already happened.

Leaders all across Europe who, for too long, have limited themselves to the more celebrated traits of agreeableness are now beginning to admit their mistakes. This is because the public has started to realize that something has been missing in the decision-making process of their leaders. As a result, “left leaning” politicians have created a vacuum that EU member states are filling with “right leaning” politicians that, in some cases, come with populist tool belts disproportionately stocked with assertiveness. Extremes on both sides should be avoided; neither the pushover nor the disagreeable brute is well-suited to lead.

In the past, proponents of equality resisted caricatures of the sexes and encouraged resistance to stereotypical perceptions of masculinity and femininity. Such a perspective acknowledged and celebrated the positives that were traditionally associated with each sex. If our current age continues to reject this; if it continues to embrace the restrictions of identity politics and, in so doing, continues to pathologize masculinity, the consequences will be a political class and polity that is no longer equipped to meet the complex challenges they will face. The stakes are high. By attempting to avoid disagreeableness at all costs, western society runs the risk of losing all that assertiveness established in the formation of our liberal democracy.

Glen Paul Hammond has a Master of Arts in English Literature from the University of Toronto. His publication credits include the educational book, The Literary Detective, and a forthcoming collection of short stories, entitled, Even the Moon is Frightened of Me, from Political Animal’s sister imprint, Crowsnest Books. Satirical cartoons and more of his writing can be found on his blog, SCRATCH.

Image: Elizabeth the First, from the Armada Portrait

Works Cited

British Library. “Elizabeth’s Tilbury Speech,” Timelines: Sources from History, www.bl.uk.

Accessed 26 March 2018.

Cherry, Kendra. “The Big Five Personality Traits: 5 Major Factors of Personality.” VerywellMind, 23 Feb. 2018, www.verywellmind.com.

Ferguson, Niall. “Angela Merkel is about to pay for all her blunders.” Boston Globe, 26 Feb 2018, www.bostonglobe.com.

“Five-Factor Model of Personality.” Psychologist World, www.psychologistworld.com. Accessed

26 March 2018.

MacGougall, Andrew. “Justin Trudeau is between a rock and a heart place on immigration.”

Maclean’s, 24 Aug 2017. www.macleans.ca.

Peterson, Jordan. “What is more beneficial in all aspects of life; a high EQ or IQ? This question is based on the assumption that only your EQ or IQ is high with the other being average or below this average.” Quora, 6 May 2016, www.quora.com.

Sjursen, Katrin E. “What the Middle Ages Show About Women Leaders.” The Atlantic, 8 Feb. 2016, www.theatlantic.com.

Villeponteaux, Mary. “Dangerous Judgments: Elizabethan Mercy in The Faerie Queene.” Spencer Studies: A Renaissance Poetry Annual, Vol 25, (2010),pp. 163-185. University of Chicago Press. JSTOR. Web. 26 March 2018.

The showdown with Khrushchev, which involved the risk of all out nuclear warfare, proved critics wrong. Kennedy took an unflinching, confrontational stance that was, upon the successful and peaceful conclusion of the conflict, celebrated as a show of strength.Hva er ADD