By: Richard Oxenberg

Let me begin with a simple observation: The God of the Bible – or, better, God as he is literally depicted in the Bible (and here the use of the masculine pronoun ‘he’ is entirely appropriate) – does not exist.

The evidence for this is overwhelming. Perhaps the most telling is, simply, that if such an entity existed he would make it clear to us. The Bible tells us, “Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, with all thy soul, and with all thy might” (Dt. 6:5). It tells us “Thou shalt have no other gods before Me” (Ex. 20:3). It presents us with command after command to be followed on the authority of this God. Clearly, this is a God who wants human beings to know that he exists and to trust him and obey him.

So, then, why would such a God hide himself from us? Why would he allow us to flounder about in confusion? Why would he allow us to wonder whether Judaism, Christianity, Islam, or atheism has it right? Why would he not make his existence as clear to us as the sun’s existence, or the moon’s existence, or the existence of anything whose existence we do not question?

Theologians twist and turn trying to answer this question, but the bottom line is that there is no good answer. The reason this God does not make his existence clear to us is because he does not, in fact, exist – at least not as he is literally depicted in the Bible and in Western religion in general.

This forces upon us the following conclusion: Either the depiction of God as presented in the Bible is entirely bogus, or it points beyond itself to something true and real that somehow lies behind the literal portrait.

Why might someone embrace the latter conclusion as opposed to the former? Because, while recognizing that God, as literally portrayed in the Bible, does not exist, he or she nevertheless feels or intuits something eminently meaningful in the biblical text, and, more generally, in the religious urge itself, to which the Bible speaks.

Just what that something is, now, becomes a matter of inquiry and investigation. For such a person the Bible becomes, not an unquestionable body of divine revelation, but a work that opens one up to question upon question concerning the nature, meaning, and purpose of human life. It is a book with which to wrangle, wrestle, debate, agree and disagree. It is a book demanding interpretation, qualification, speculation, criticism, even suspicion. Such a person’s religious convictions, never altogether fixed, are formed as much from self-inquiry as from a reading of the text; they are formed from a dialogical interchange between text and self, a creative engagement in which self-understanding is used to illuminate the text, and the text itself is used to point toward new possibilities of self-understanding.

Such a person will recognize that her own engagement with the text will, of necessity, differ from others’ engagements with the text, and will understand, therefore, that there can be no absolute, definitive, unqualified, unalterable, infallible, engagement with the text. For her, in other words, the dogmatic principle of biblical infallibility will be reversed; she will adopt a principle of biblical fallibility, recognizing that the process of reading the Bible, first of all, is a process (of creative engagement), and second of all, that it is, therefore and necessarily, a fallible process – as fallible as we ourselves.

So, then, what are we to understand by the biblical God?

Here, anyway, is a brief account of what I have arrived at through my own creative engagement with the text:

I see the Bible as pointing to a fundamental Oneness of reality as a whole, underlying the diversity of ordinary, worldly, experience – a Oneness that we are to recognize, commune with, devote ourselves to, and, finally, rest in. Such Oneness serves as a counter to, and resolution of, our basic human experience of separateness, division, exclusion, isolation, death. Association with the Oneness that transcends our separateness can bring us to a state of peace within ourselves and among ourselves: “Though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death [separateness, division, discord, destruction],” says the psalm, “I fear no evil, for Thou art with me.”

This Oneness the Bible names ‘God,’ and represents as if it were a distinct person acting in the world for the sake of fostering an awareness of itself, and of the moral and spiritual attitudes infused by it.

But this Oneness is not really a separate person standing apart from us, making demands on us for its own idiosyncratic purposes. It is, rather, the very ground of our being (to use a phrase popularized by Paul Tillich). Its calling to us is our calling to us; a call to pass beyond our experience of isolated separateness (ego) to an experience of the Unity that underlies all separateness – a sacred Unity that joins us to reality as a whole, to other sentient beings in general, and to other human beings in particular. Such an experience has both an existential and an ethical dimension. Existentially, we come to experience our rootedness in that which is fundamental to being, an experience that lifts us out of our sense of lonely isolation. Ethically, we come to recognize our essential commonality with others, which fosters compassion for them and a demand for justice. Spiritual life is the life of growing toward this experience of Unity.

As one comes to see that this is what the Bible points to, one also comes to see the Bible’s essential affinity with all the great religious traditions of the earth, both Western and Eastern, for one sees that this is the central message of all of them. Thus it becomes impossible to affirm Judaism over Christianity, or Judeo-Christianity over Buddhism or Hinduism. One comes to see that all the world’s religions are ‘fingers pointing to the moon,’ each imperfectly pointing to a perfection no one of them perfectly embodies, each to be appreciated for what is good and right and true in it, and to be scrutinized, criticized, challenged, and, hopefully, corrected, for the ways it misses the mark.

Thus one comes to see – ironically – that one must transcend the Bible to be true to it; that ‘to love God with all one’s heart, mind, and soul,’ requires that one not cling to one particular religious form and condemn all others; that to do so, indeed, is to violate the spirit of the second of the Ten Commandments; it is to turn the Bible itself into a ‘graven image’ of God.

And this is a message the Bible itself delivers to us. The prophet Jeremiah writes: “Thus says the Lord of hosts, the God of Israel: Amend your ways and your doings, and let me dwell with you in this place. Do not trust in these deceptive words: ‘This is the temple of the Lord, the temple of the Lord, the temple of the Lord’” (Jr. 7:3-4).

‘Temple’ here refers to the particular institutional form of ancient Israelite religion. We are not to put our final trust in such religious forms, says Jeremiah. Rather we are to “amend our ways and our doings” – ourselves – so as to learn to dwell in peace, in harmony and joy, with one another, and with the One who lies beyond all forms, and upon whom all forms rest.

Richard Oxenberg received his Ph.D. in Philosophy from Emory University in 2002, with a concentration in Ethics and Philosophy of Religion. He currently teaches at Endicott College, in Beverly MA.

He is the author of the book, On the Meaning of Human Being: Heidegger and the Bible in Dialogue, published by Political Animal Press.

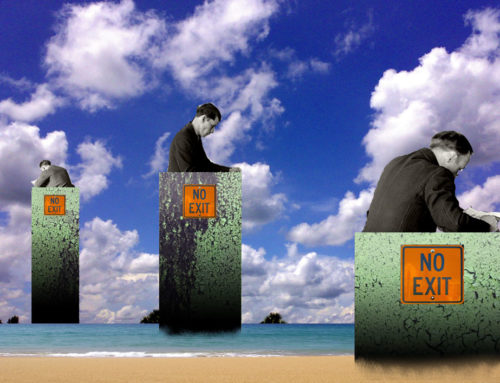

Image: The Vision of Saint John, or The Opening of the Fifth Seal , El Greco (1608 until 1614) via the Metropolitan Museum of Art, online collection

This is an excellent article with persuasive points. I’d like to know more, however, about how this discussion of religious scriptures pointing to a transcendent One accounts for a second function of nearly all religious texts: the realization and maintenance of religious experience in concrete, historically specific communities. Transcendence is a noble concept and accurately describes an important aspect of religious experience. On the other hand, though, religious experiences of a universal One tend to channel themselves into specific communal allegiances and practices. A great deal of the biblical literature, for example, deals more with managing community (legal material, historical narrative reinforcing identity, etc.) than with trying to identify the nature of the One. These practices depend on the experience of the One and might even be seen as practices (rituals) meant to clarify or access the transcendent One. But these communities also name the One, make specific and sometimes exclusive claims about the One, define themselves in opposition to other communities seeking the One. So how do you envision the relationship (maybe the tension) between the transcendent One and concrete instances of religious practice? Very few religious communities exist around a nebulous concept of transcendence, but rather identify specific ways that this One enters into human history. Religious texts are about the One, granted, but they are often at least as concerned with how those who more or less share a common concept of the One form communities. Thanks for a great article, and I hope to learn more.

Thank you for a very provocative question, Rich (and sorry for my rather long delay in responding – I haven’t been monitoring the comments and I just saw this.)

I write in my article that “I see the Bible as pointing to a fundamental Oneness of reality as a whole, underlying the diversity of ordinary, worldly, experience – a Oneness that we are to recognize, commune with, devote ourselves to, and, finally, rest in.”

I think that this statement is true in essence, but I would also say that, as an account of what the Bible is as a whole, it is not complete. The Bible, as scholars note, is the work of many hands, an interweaving of multiple texts, many of which are themselves rooted in oral traditions that doubtlessly underwent many transformations before being fixed in written form. So the God who appears in the Bible is a multi-faceted and multi-layered figure, which, as I say, “points to” the “fundamental Oneness” of which I speak, but is also an imperfect reflection of such Oneness. This is why I say that we must adopt a principle of biblical fallibility in reading the Bible. We cannot assume that every passage of the Bible is a perfect, or even true, reflection of divine Oneness.

My own view is that the biblical authors are (for the most part) inspired by some vision or intuition of this Oneness and its significance, but that this inspiration is never pure. As Paul writes, “we see through a glass darkly.” That dark glass is our own, less than fully sanctified, nature.

I think you make a good point when you say, “A great deal of the biblical literature, for example, deals more with managing community (legal material, historical narrative reinforcing identity, etc.) than with trying to identify the nature of the One.” That’s very true.

And yet at the heart of the Torah is the command: “Hear O Israel, the Lord our God, the Lord is One, and you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, and with all your strength.” It is in the context of this overarching command that the other commands are issued.

What is being said here (as I read it) is that Israel in particular, and, later, through Christ, the whole of humanity, is to live in a manner that reflects the Oneness of God (and, by implication, the unity of the creation and the solidarity of human beings). Love and justice are the spiritual and moral expressions of this Oneness. The specific commandments – at least ideally – are intended as means to the end of establishing a loving and just society.

But again (as the Bible also documents) human beings regularly fall short of this ideal, and the Bible itself, as a text, falls short of this ideal. That is why we are ever called on to do the hermeneutical-theological work of wrestling with the text, and with the order of the communities formed around the text, in order to make both better reflect the ideal.

I hope that is helpful as a response to your very rich question. And thanks again for your comment!

Thank you, Richard, I appreciate your reply. I recently had the chance to lead a conversation on some of the wisdom literature contained in (various versions of) the Bible, and noted in the group (as others have) that the wisdom literature in particular is primarily directed at individuals rather than communities. This part of the biblical literature may be more relevant to the *existential* concerns of any reflections that take Heidegger as seriously as your article and book do. In other words, among the concerns of the individual (existential concerns) would be the ability to access and experience the transcendent One, whereas for the community (the religious community) the ability to gather around a common understanding of the One might take precedence. In any case, thanks for your thoughts!