By: Marco Senatore

In a world where money is the only universal means of exchange, how different would society be if racists had economic incentives to embrace human rights, and the average citizen found it profitable to foster democracy? In this article I will attempt to answer this question.

Last year the neoliberal narrative suffered a major blow in the United Kingdom, with the vote for Brexit, and in the United States, with the election of Donald Trump as President. By neoliberalism here I mean that political and cultural model that subordinates every public decision to economic rationality, and adapts the state and the whole society to the needs of the market. More specifically, I include in neoliberalism the Ordo-liberal School that influenced the architecture of the Economic and Monetary Union, the Chicago School, the so-called Washington Consensus and, somewhat, the Third Way developed during the 1990s. Beyond its economic principles, neoliberalism has also been important in supporting human rights and rule of law, as they facilitate the functioning of the markets.

In the current juncture, highlighting the risks of populism and of post-truth is an important and useful exercise. It is obvious that the manipulation of facts, racism and other forms of discrimination make populists much more dangerous for democracy than most politicians who have ruled the world in the recent decades.

However, in order to change some of the paradigms that are shaping the political debate in America and – to a less extent, after Macron’s election – Europe, it would be essential to deal also with the flaws of that neoliberal order, whose contradictions have helped the rise of populists. After recalling some elements that are shared by populism and neoliberalism, I would like to propose two forms of social interaction, aimed at overcoming these elements.

First of all, both populism and neoliberalism endorse “economicism”, or the prevalence of the economy on every other dimension of life. On one hand, neoliberalism has constantly assumed that material welfare is the main factor behind human actions. Neoliberals have also claimed, at least until the last financial crisis, that free markets automatically foster other forms of freedom. On the other hand, populists try to rely mainly on the economic hardships suffered by the middle class in order to get their consensus. We will hardly hear Trump complain about how the establishment overlooked the spiritual and emotional welfare of citizens, whereas his criticism focuses on the economy, mostly on job destruction caused by delocalization of firms. “Economicism” is also strictly connected with the dominion of instrumental reason that, according to Max Horkheimer in his critique of Enlightenment, enslaved humans.

Populism and neoliberalism also share the assumption that citizens are merely individualist atoms, striving to pursue their self-interest. This assumption is greatly confirmed by the mainstream theories of economics, with a few exceptions that include Amartya Sen. By individualism I mean the possibility to freely choose the best means – curricula, ideology, profession – to pursue some given aims – once again, mostly material welfare. But neither populism nor neoliberalism care a lot about individuality, as the possibility for a human being to challenge the mainstream view about the most desirable aims and what makes a good life.

Beyond “economicism” and individualism, both populists and neoliberals tend to marginalize dissent: the former condemn any criticism as a form of complicity with the establishment, whereas the latter have been defining as dangerous and unorthodox any doubt on the virtues of free, open and often unregulated markets. However, the lack of diverging views is not healthy for democracy. Indeed, Hannah Arendt observed that the heterogeneous uniformity of mass society is one of the primary conditions for totalitarianism.

Against this backdrop, I find that any project aimed at overcoming populism should not only be tactical and political. It should be a strategic, long- term, cultural project aimed at redefining capitalism. This should imply defeating “economicism”, individualism and social homologation.

In order to achieve this, we should give a stronger, formal role to moral, organizational and cultural values. Indeed, values are non-monetary, non-economic resources that can inspire many human activities. Values are also relevant elements of individuality. And they can be the basis for a public, rational debate on social issues, which prevents mere homologation.

Therefore, also with a view to fostering individuality and reconciling economic utility with autonomy, I have formulated two proposals, that consist in establishing exchanges of values and communities of individuals who share the same values.

As for the first proposal, individuals, legal persons and communities might exchange documents describing relevant experiences – certified by third parties (e.g. private operators) on the basis of commonly agreed indicators- that attest to the positive role of some values. This could refer to moral values (such as social justice), organizational values (such as propensity to innovation) and cultural values (such as multiculturalism). These documents would also describe the actions that have been concretely inspired by those values. The relevant experiences referred to each value would be priced on a market, on the basis of supply and demand.

For instance, a given U.S. State (let’s suppose Montana) might purchase a document referred to social justice, that describes social measures adopted by another State (for instance, California) to foster equity and inclusion, and the benefits of these measures in terms of reduced crime and greater cohesion. After undertaking its own initiatives, and reducing inequality (for instance, the Gini index by a certain percentage), Montana might add its own experience to the document, and transfer the latter on the market.

Each document might be exchanged with documents referred to other values, so that, for instance, the State that has fostered social justice might receive the description of experiences referred to environmentalism. And if values could be used also as a means of exchange complementary to money (i.e. if values could be used to buy goods and services), this would create an economic incentive for communities to adopt certain policies, and for individuals to undertake certain activities, in order to enlarge the set of experiences that they own. Considering values and inner motivations for what they are – a form of capital, able to inspire professional and personal activities – would be a way to reconcile the existential dimension of individuals and the cultural dimension of organizations with their social role. And the human being would no longer be simply what Hannah Arendt called an animal laborans, which means an alienated individual deprived of that freedom from himself and his immediate needs, that denotes an authentic active life.

Such transactions would also allow individuals to endorse values that are not necessarily instrumental to their profession and direct needs, and that are also different from the dominant views. This would mean fostering functional autonomy. Functional autonomy, I define in my book, Exchanging Autonomy: Inner Motivations as Resources for Tackling the Crises of Our Times, as the condition whereby the judgment on one’s socioeconomic reality influences one’s social role, rather than being influenced by such role. As values would be a means of exchange complementary to money, adding new relevant experiences would make it possible to reconcile authentic individuality – not mere individualism – and economic utility.

This would also be important to reach that veil of ignorance that, according to John Rawls, should characterize our choices on justice, in the sense that they should not take into account what role we have in society. And it would also contribute to the existence of authentic communities, of which the functional autonomy of individuals is a necessary condition. Indeed, a community is formed by people who grant it with an intrinsic value, and not simply the task to ensure a safe coexistence, like it happens with Hobbes’ absolute State, or any social contract. And a community – something very different from a mass society – cannot exist where individuals are not autonomous, because their choices are only based on their role of consumers and workers.

A second proposal that I have formulated deals with the fact that many individuals, who hold values such as social justice and environmentalism, have social roles that are inconsistent with these values. What we believe in is a medium that can connect us with other individuals, like money and power. But people who give us money (our employers or customers) or who receive money from us (our employees or suppliers), often pursue social aims that are totally opposite to ours. And the same happens with people who have power on us (politicians) or who share the decisions taken for us (other citizens). Against this backdrop, individuals who share some given principles might interact in order to reach a critical mass, able to influence money and power. This would take place through forming local, autonomous communities and, subsequently, national and global networks.

In particular, the Internet should play an essential role in allowing employers, employees and volunteers to identify counterparts who share their vision of the world, and who might therefore pursue the same social aims (e.g. a given reduction in CO2 emissions in their region). For instance, the manager of a green company, who does not have the opportunity to contribute directly to human rights in his area, might hire engineers, who are active in helping refugees, and who have not found decent jobs, because they don’t want to work in a polluting plant. Through these forms of cooperation, similar to the spirit of peer-to-peer communities, individuals who share some values would fulfill their aims, without just delegating them to the economy and politics.

After the establishment of cooperative groups and the achievement of common objectives (a phase of emancipation), these communities would go through a phase of expansion, aimed at including more individuals and businesses in their network. This would take place through providing incentives to the economic system to cooperate with the communities. These incentives might include: higher labor productivity ensured by lack of alienation; the economies of scale linked with the presence of workers and suppliers who share the same values; trade opportunities among, for instance, communities of different countries. And also the political system might become aware of the social benefits of the initiatives undertaken by value-based communities.

These two proposals are quite different from each other. The first one has the ambition to give an economic role to moral, organizational and cultural values, to the point of considering them as a means of exchange complementary to money, as well as a form of capital beyond the three forms of money-capital, commodity-capital and productive capital, identified by Karl Marx. The exchanges of values could connect individuals and organizations with very different backgrounds.

The second proposal highlights the role of groups of individuals and organizations that share the same values, and that are therefore able to influence the rest of society.

In both cases, however, economic rationality is not seen as an end in itself, but as a means to foster individual autonomy, create a sense of community and spread values different from mere economic utility.

In our age, we need a new approach to social issues. An approach based on interdisciplinarity, and on the integration of human values with the formal institutions that regulate our daily interactions. This is needed to avoid populist, egoic identifications with negative feelings that take the place of individual autonomy. But this is also needed to counteract the commodification, standardization and dehumanization of our lives.

Marco Senatore is a civil servant. After graduating in Political Sciences at the University of Rome, he has worked at the Ministry of Economy and Finance of Italy and at the Executive Board of the International Monetary Fund.

Marco is the author of the interdisciplinary book “Exchanging Autonomy. Inner Motivations As Resources for Tackling the Crises of Our Times”. His articles have been published, among others, by the London Progressive Journal, the think tank Compass, the journals Philosophy for Business and Notizie di Politeia. Marco’s Twitter account is @MarcoSenatore75.

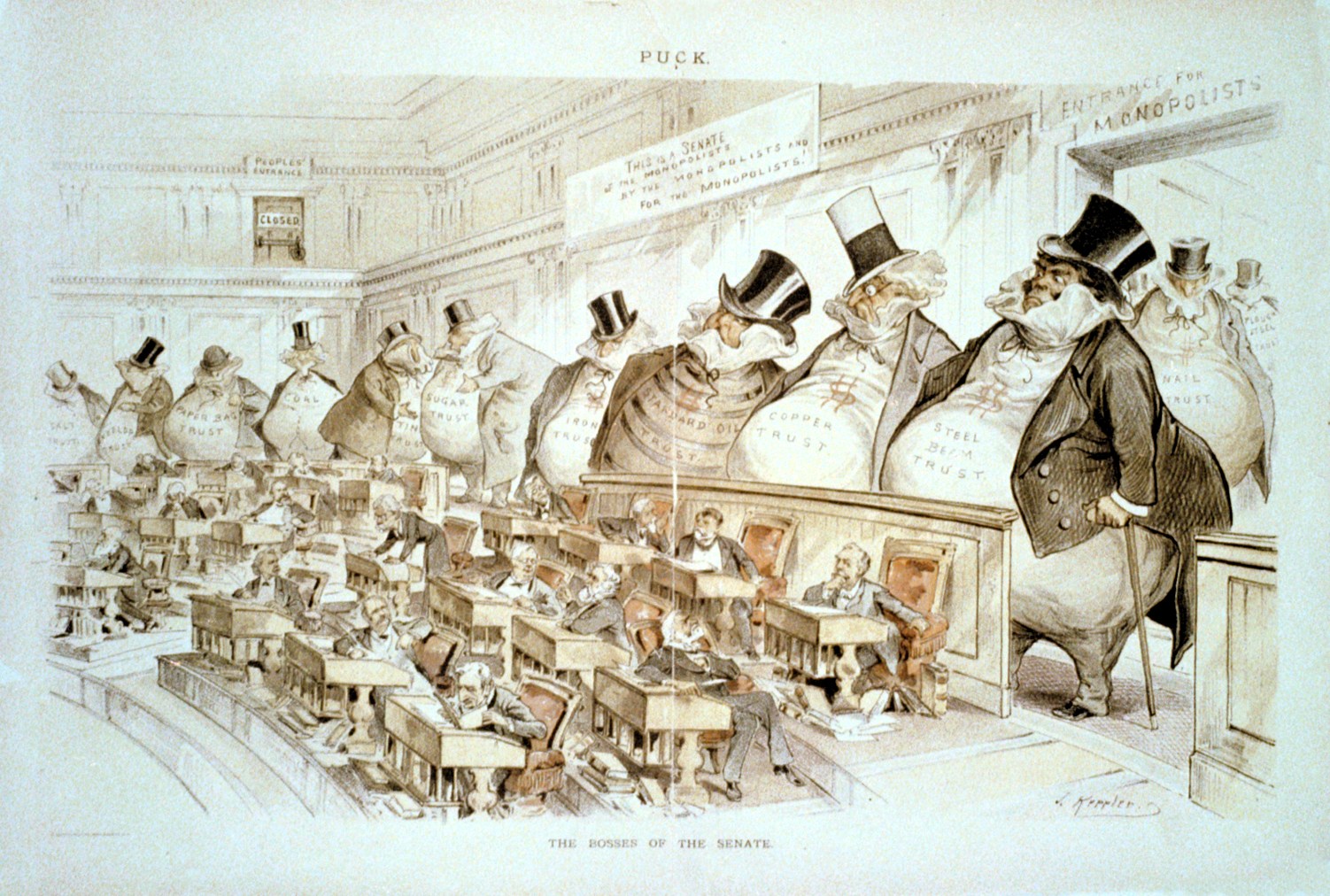

Image: The Bosses of the Senate, a cartoon by Joseph Keppler. First published in Puck 1889.

I saw the following comment on a Reddit thread about this article and thought it was really on point, so I’m putting it here:

“It is difficult to see how these two proposals are much different from the special interest groups we already have.

The first proposal suggests that states that have successful policies should sell those solutions to other states, but we already have that for free (and it’s unclear how they would even enforce the intellectual property as that data is typically public knowledge). Interest groups aggregate that data and present those solutions to politicians either as a fee-based lobbying firm or a non-profit. Similarly in the private sector you can higher consultants and firms for fostering a certain ‘culture’ in the workplace.

As for the second proposal of connecting like-minded people for business, again this already happens with businesses donating to certain causes and taking stances on political/social issues. These businesses often use this as a selling point when recruiting. Generally these causes tend to be non-controversial (donating to poor kids) but there are some with clear opposition (serving gay partners, refusing contraception, transgender, etc.) If you want to hire like-minded employees (though the societal benefit of this is unclear as with the filter-bubble polarization we are experiencing), I’m sure many interest groups would also be open to posting job offerings if you’re a big/regular donor.

I do agree that we need to counteract dehumanization and commodification in the market but I fail to see how commodifying culture would accomplish that, as the author seems to be suggesting.”

“how different would society be if racists had economic incentives to embrace human rights, and the average citizen found it profitable to foster democracy?”

Is this the same as asking, ‘can’t we just PAY people to stop being racist and to support “democracy”‘?

Regarding the comments to my article, that I read above, let me clarify some points. Thank you both, in any case.

To Kurt W.: I find the reference to intellectual property misleading, to the extent that the values traded, according to my proposal, would not be the outcome of a technical process or innovation. The application of values, while open and public, would just require to be assessed on the basis of some commonly agreed indicators, such as, in the case of inequality, the Gini index. There would not be the creation of a new product, of new goods or services. Values are motivational resources, not the outcome of a production process.

The reference to interest groups (lobbies or non-profits) is also not strictly accurate to comment on my first proposal, as the “seller” of values (or, more precisely. of documents describing the importance of some values) should have directly experienced and applied principles such as social justice (for States), learning by doing and innovation (in the case of companies), flexibility (in the case of individuals). On the other hand, interest groups typically advocate measures and interventions that are instrumental to their own interest (as the name says). These groups are not aimed at spreading values (i.e. criteria for judging reality, changing it or keeping unchanged), but simply at making professional activities and social roles more profitable, whereas values and activities have to be found on two different, distinct levels.

My proposal is also different from a mere attempt to spread a certain “culture” in a workplace. What I propose has the potential to provide an alternative to work as the only, standardized and often alienating way to receive an income; and, in any case, it has the potential to let people consider values as an element able to inspire a change in one’s personal and professional activities. If we remain in the mindset of considering values as part of “culture” of a given place or environment, then we remain in the area of heteronomy, for which beliefs are only the consequence of a social role (and, therefore, society is only a contract signed by individuals on the basis of “private”, instrumental values). Exactly the opposite of what I suggest.

As for my second proposal, I am aware that some forms of cooperation already exist, between employers and employess or among companies, aimed at fostering some causes. But this is not relevant to assess my scheme, that is based on the creation of networks and communities that share some projects, on the subsequent assessment of the comparative advantage that these causes provide, and on the extension of the networks and communities, on the basis of economic and political incentives. Your examples are randomly selected, whereas I suggest an alternative or at least complementary, but systemic new form of social interaction (comparable with peer-to-peer communities).

As for the idea that my proposals would “commodify culture”, this is quite surprising, at least if we have read authors such as Theodor Adorno. Since almost one century, philosophers have kept telling us that a culture industry and a mass society are endagering real freedom and democracy. I cannot really see, then, where the scandal would be, in a world where almost everything is a commodity, if individuals and companies could simply buy and sell documents describing personal experiences. The point is not if I sell or if I give a present. The point is: are we giving something that has an intrinsic value or that is purely instrumental to the social fabric?

To Delphi79: “paying” and “giving economic incentives” are not the same thing. Paying is just giving money, presumably with the hope that some behaviors will be changed, but without any interest in the actual application of values such as tolerance. The economic inventives that would be provided through my schemes, on the other hand, would require individuals to be actively involved in initiatives that are aligned with some given values. Adopting values would be a form of investment, as well as a form of self-expression through a precise moral and cultural identity.

Thank you again.

Thanks for responding! I saw this further response to your latest remarks on Reddit, so I brought it over here, like I did with the original comment:

“Ah, a reply directly from the author, fantastic! If you don’t mind, your proposal is still a bit confusing to me and I would appreciate some clarification on some or all of these points:

1. If this ‘experience document’ is not intellectual property, how can a state expect to make money off of selling it? And how is this different from what think tanks and other NGOs already put out for free?

2. In several parts of the article you seem to suggest that “values” can be used as a means of exchange. Again, without intellectual property or some ownership of the material, why someone would give up a good, service, or currency to obtain such a document? Perhaps if it were a consultancy fee or some kind of training to foster a value (as values/behaviors/motivations cannot be instantly adopted and must be continuously worked on), but you are suggesting simply a document describing experiences can have a high market price?

3. I’m having trouble understanding how your second proposal reduces alienation. Do you believe that it is less alienating to do work when you know that your boss has similar political/moral beliefs as you? Unless the business as a whole actually acts in a manner that I agree with, how my boss thinks won’t reduce alienation except insofar as we have improved compassion with each other as a result (and this interhuman compassion can happen with people who believe differently from you). If this proposal does relate to company-wide missions, how does your proposal differ from job applicants seeking out companies with a reputation for goodwill/sustainability or are known for doing charitable work in their preferred cause?

4. Probably the main source of my confusion is the idea that it is possible to “buy” values. For the most part, values are something ingrained in people from socialization and experiences. If one consciously desires to change certain values within themselves, one must put in a sustained effort over time to make that change. Someone selling me a document of their “experiences” doesn’t make me instantly adopt their values at an unconscious level even if that’s what I consciously want to do — our brains aren’t designed to make sudden changes in personality like that. Unless I’m missing something; how do you envision the actual adoption of values to work after receiving an “experiences” document?

Thank you for your response. You describe problems that I am interested in solving, but I can’t quite wrap my head around your solution.

-Vladimir”

Kurt W.,

thank you for the further very important questions raised by Vladimir. They help me to clarify some aspects of my proposals. I am also available for further clarification (my Twitter contact is indicated at the end of the article). Coming to the questions:

1. As regards the role of the State in exchanging the documents that I referred to (and that indeed we could call experience descriptors), it would not be substantially different from the role of private operators (companies and individuals): States, companies or individuals would purchase these documents, analyze them in terms of feasibility of the policies and initiatives that they describe, and sell (or exchange with other documents) them after widening – through applying the values – the lists of experiences. The price of each document would be the sum of the prices of the relevant experiences referred to a given value, that would be determined by demand and supply on the market. Therefore, each holder of a document could sell it at a price higher than purchase cost, because of two factors: on one hand, a possible increase in the demand –and, therefore, price – of relevant experiences referred to that value; on the other, the circumstance of adding new experiences to the document, through the exercise of one’s autonomy. The State could also regulate the market for values, in the sense of deciding, for instance, which values would be exchanged for a certain period of time. In the current juncture, spreading environmental values should clearly be a priority.

On the role of think tanks and NGOs, I totally agree that they provide an important contribution to spreading some values. In my scheme, the different element would consist in giving an economic incentive (i.e. the increase in the price of the document) to adopt some values also to companies and individuals that operate in another sector, not related with those values, or that constantly stood against them.

2. According to my proposal, as described in my book “Exchanging Autonomy. Inner Motivations As Resources for Tackling the Crises of Our Times”, each value (e.g. environmentalism) could be exchanged with other values (e.g. social justice), or with goods and services. This latter possibility would make of values a means of exchange complementary to money. The reason for this consists in giving an economic incentive to apply the values, without practicing mere speculation on the price of the documents. This is also why values should not be exchanged directly with money. While ideally values should only be exchanged with each other, and such transactions should only have the purpose of adopting values independent from one’s social role (what I call functional autonomy), the idea of making of values a means of exchange complementary to money would also be consistent with considering them as a form of capital, that can be used to inspire professional and personal activities. Again, in general the economic incentive to buy something is not the level of its market price, but the expected change in this price. And the adoption of values strongly requested by the market, the addition of several experiences to the document, or, most likely, both circumstances, would ensure the profitability of the investment represented by the purchase of a given value.

3. On the issue of alienation, I do believe that a worker can perceive a job as more fulfilling, as the literature confirms, in an environment that shares his core values. But, in the case of my proposal, workers would not only know that their boss or coworkers support their ideals: they would also know that, through the cooperation on common objectives, some values would have a chance to have a real impact, an economic viability and, therefore, a likelihood to be spread to other companies and organizations, or parts of society. I fully agree that there are already many situations in which job applicants seek out companies with reputation for some values, and this is a very important development of our times. However, those values are, in most cases, instrumental to a different, or at least wider corporate mission and, in a nutshell, profit. My proposal would make of values an end in itself, to be pursued through forms of cooperation mostly at the local level. Another difference consists in the fact that these forms of cooperation would be able to generate spillovers to the rest of the regions involved, through economic and political incentives.

4. The idea of buying and selling values can be considered, if you will, a provocation aimed at highlighting how our beliefs and criteria for judging reality, while apparently free, are actually strongly influenced by our social role of consumers, workers, producers. A relatively little share of the population can freely choose what job to do, based on general principles such as social justice, environmentalism and so on. But my proposal is much more than a provocation. It’s the attempt to give a formal, economic, legal role to those inner motivations (values and, as I argue in my book Exchanging Autonomy, metavalues) on which a rational, public discourse is totally absent. Now, purchasing a document that contains relevant experiences of a given value would not mean to change one’s personality or to renounce one’s ideals. It would simply be an opportunity for an individual to invest part of his resources in a different, new form of activity, and concretely apply his beliefs as well as widen them. I want to stress that the relevant experiences would be certified on the basis of commonly agreed indicators (for instance, in the case of environmental values, the percentage of investment devoted to renewables), and, therefore, adopting values would not imply an abstract, simply existential change: it would mean changing the way in which businesses, workers and consumers operate. If you will, by “values” I mean “modalities to perform certain activities, and the aims of these activities”.

I think my clarifications have been quite detailed, and consistent with what argued in my book “Exchanging Autonomy” and in other articles.

Thank you again,

Marco Senatore

None of above makes sense!!!!!