By: Richard Oxenberg

I. Introduction

I would like to begin with a bit of a riddle: How do you turn a democracy into a tyranny? The answer, as those familiar with Plato’s Republic will know, is: Do nothing. It will become a tyranny all by itself.

Plato spends a good part of the Republic developing his argument for this, and yet the gist of that argument can be found in the word ‘democracy’ itself. ‘Democracy’ is derived from two Greek words: ‘demos,’ which means ‘people,’ and ‘kratos,’ which means ‘power,’ and might be defined as ‘power of the people.’ This corresponds with Abraham Lincoln’s famous designation of democracy as “government of the people, by the people, and for the people” – which he hoped would not perish from the earth.

But what exactly are we to understand by the word ‘people’? I can illustrate the problematic character of this word through the title of a book I was assigned to read many years ago when studying for my Bar Mitzvah. The book was entitled, When the Jewish People Was Young. Even as a twelve year old the title struck me as grammatically odd. Shouldn’t it be: When the Jewish People Were Young? No, because the word ‘people,’ generally a plural, was here functioning as a singular. The phrase ‘The Jewish People’ was not intended to refer to a multitude of Jewish individuals, but rather to a singular entity made up of these individuals.

May we say the same about democracy? When we define democracy as ‘power of the people’ are we using the word ‘people’ in the singular or the plural sense? Do we mean a collection of separate individuals or do we mean some singular entity made up of these individuals?

It’s not altogether clear. Indeed, it turns out that however we answer this question we run into problems. If by ‘people’ we mean a multitude of individuals, then what can it mean to say that power is vested in the hands of the ‘people’? Which people? Surely a collection of individuals, each pursuing his or her separate ends, cannot be expected to achieve unanimity in all, or even very many, matters of importance. If, on the other hand, we mean by ‘people’ a singular entity made up of these individuals, then how are we to understand the relationship between these individuals and that singular entity? Do the individuals owe the entity allegiance? Must they put aside their private interests for its sake? And what, anyway, is this entity? Does it have its own distinct reality as a thing unto itself? Or is it merely, in the words of Jeremy Bentham, a “fictitious body”? If the latter, what rightful claim can a mere “fictitious body” make upon the very real individuals who compose it?

We can further examine this problem by considering the phrase, lifted from the U.S. Declaration of Independence, ‘government by consent of the governed.’ Consent of the governed, Thomas Jefferson tells us, is the principle upon which the just powers of government rest.

But what if all the governed will not consent to the same directives of government? On what basis should conflicts of interest be decided? The simple, but clearly wrong, answer is ‘majority rule.’ The principle of majority rule, applied to the antebellum South, for instance, would have justified slavery. Jefferson’s own answer was ‘natural rights.’ Government exists to protect our natural rights. But what are natural rights? Where are natural rights? And how can a citizenry who cannot see, touch, taste, smell, or hear these natural rights be expected to govern their lives in accordance with them?

Various theorists of liberal democracy will have their various answers to these questions. It is not my purpose to explore these answers, but to touch upon an issue fundamental to all of them. In order for any of these answers to be effective citizens must be able to recognize a species of truth – moral truth – that is, so to speak, trans-individual. They must be able to apprehend, intellectually, moral imperatives that derive their legitimacy from something more universal than the individuality of individual interest.

The need for this has become especially evident in our current political year. Increasingly, spectacle and entertainment pass for news, inflamed passions take the place of reasoned reflection, insult and invective substitute for rational critique. Our very capacity for sober, disinterested, judgment seems to have been compromised. Observing this, Plato would be chagrined, but not surprised. He would see it as a function of the democratic form itself. The specific problem Plato saw in democracy is that, through its emphasis on the supremacy of strictly individual desires and interests, it tends to undermine our capacity for recognition of the self-transcending universal truths upon which a just society must be founded.

How, then, does a democracy turn into a tyranny? It’s the epistemology, stupid!

II. Philosopher-Kings

Let us consider Plato’s critique of democracy more closely. Plato writes: “In a city under a democracy you would hear that [freedom] is the finest thing it has, and that for this reason it is the only regime worth living in for anyone who is by nature free.”[1]

A society dedicated to individual freedom would seem the diametric opposite of one under the oppression of a tyranny. But here we encounter a paradox. For the ideal of individual freedom, where such freedom is understood as the liberty to exercise one’s will without restraint, is the ideal of the tyrant as well. Indeed, we might define the tyrannic character as, precisely, a character who is unwilling to submit to any higher principle than the unrestrained exercise of his or her own private will. Thus, ironically and paradoxically, democracy – at least where individual freedom is heralded as its highest good – shares the same ideal as tyranny. What Plato saw is that a society that presents to its citizens no higher ideal than the freedom to satisfy private interest, will, by that fact, become a society of aspiring tyrants, competing each with the other for dominance. Eventually, those most skilled at the arts of grasping and manipulation will come to lord it over everyone else, and the society that most exalted freedom will become the one that is most enslaved.

What might the defender of democracy say to such a charge? What she would have to say, I believe, is something like this: As a matter of fact, individual freedom is not the ideal on which a true democracy is founded. Rather it is founded on the ideal of respect for individual freedom, one’s own and others. It is just such respect that the tyrant lacks, and, hence, a sharp distinction can indeed be drawn between the democratic and tyrannic ideals. Democracy demands that individuals curtail the unbridled exercise of their individual freedom where such exercise would impinge upon the rightful freedom of others.

But this distinction, between the ideal of freedom and the ideal of respect for freedom, is a subtle and challenging one. In particular, it is not so easy to say whence the ideal of respect for freedom derives its imperative force. It is easy enough to understand why we value our own freedom, as this is a direct implication of our desire to satisfy our appetites, but this says nothing about why we should value the freedom of others. We cannot derive the value of respect for the freedom of others from the value of freedom itself. On the contrary, as we have seen, where the value of freedom itself is heralded as supreme we get something far more like tyranny than democracy.

Indeed, we can take this a step further. Not only does the value of freedom not imply the value of respect for freedom, but the two stand in decided opposition to one another, at least where we understand freedom as the freedom to satisfy appetite. Appetite, by its very nature, is self-referential; it is a demand for its own satisfaction. Respect for the freedom of others, on the other hand, demands a transcendence of strictly self-referential concern. Where within us can we find the capacity for such self-transcendence? As Plato makes clear, certainly not in our appetitive nature. It is only in our rational capacity to rise above our self-referential appetites and passions, says Plato, that we can hope to achieve the self-transcendence necessary to the establishment of a just society.

It is in this context that we can begin to understand Plato’s call for a ‘Philosopher-King.’ “Unless,” writes Plato, “political power and philosophy coincide in the same place. . . there [will be] no rest from ills of the city. . . nor I think for human kind.”[2]

Plato was aware of how outlandish this proposal sounded even as he wrote it, and much attention has been paid to the despotic potential of Plato’s political vision, but Plato’s basic point remains compelling: society must be governed by leaders who are able to rise above the intensive self-centeredness of their emotional, appetitive, and egoistic impulses so as to concern themselves, wisely and dispassionately, with the common good. The only human faculty capable of such self-transcendence, according to Plato, is reason, hence only the philosopher, dedicated to the cultivation of reason, is suited for governance.

Of course, to make sense of this we must recall that Plato’s conception of reason is value-oriented. By the cultivation of reason (logismos) Plato does not mean the cultivation of mere technical acuity, but of that capacity within us that is able to apprehend the logos, i.e., the good order, of things. What we might call Plato’s ‘faith’ is that those able to see this good order will see, as well, that their own private good is best realized through it. It is just such seeing that philosophy, as a project, pursues. It is only the philosopher, then – the true philosopher – who will have the intellect, character, and (therefore) motivation to rule justly and wisely.

Plato makes it clear in the Republic that his aim is to sketch out the form of the ideal polis, not to present a practical political program. Thus, criticisms of the Republic that complain that its system will not work in practice (e.g., that the philosopher-kings will likely become corrupt, etc.) miss the point. When Plato says that a just society depends upon the coincidence of political power and philosophy he is not proposing a particular political system but making an observation about the nature of governance. Government, in principle, must concern itself with the common good. Those who govern, thus, must have both the capacity and motivation to pursue this good disinterestedly. As a formal truth, this will be true of every particular political system.

What are the implications of this for democracy? The answer seems plain: in order for “government of the people, by the people, and for the people” to avoid degeneration into tyranny, the people themselves must have something of the character of Platonic philosophers. In other words, in order for democracy to succeed it must cultivate ‘philosopher-citizens,’ whose political commitments will be to something beyond the satisfaction of private, appetitive, interests.

This implies that education, indeed a value-oriented education, is crucial to the health of democracy. Democratic citizens must be educated in democratic ideals. But here again we run into a problem. Almost everyone will agree, in a general and vague way, that education is a good thing, but many will balk, in the name of democracy itself, at any deliberate cultivation of values. Values, we like to suppose, are a private affair. Everyone in a democracy has a right to pursue what values she will. The paradox, of course, is that this assertion is itself the expression of a political value that must enjoy general currency in order for democracy to function. It is not the case, then, that democracy entails the right of everyone to ‘pursue what values she will,’ but rather those values consistent with the ideals of democracy itself.

This leads us to the question: What values must inform a democratic citizenry if they are to avoid descent into tyranny? To consider this we will look at Kant’s conception of the ideal democratic society he calls ‘The Kingdom of Ends.’

III. The Kingdom of Ends

The ideals of democracy do not have obvious roots in human nature, despite Thomas Jefferson’s celebrated pronouncement that they are “self-evident.” What is most evident, as Thomas Hobbes most famously pointed out, are the ideals of tyranny. Each of us wants what we want and would be happy to have everyone else conform to our wants. Because of this, democracy has something of a deceptive appeal. Monarchy and other forms of autocracy make it clear, however despotically, that the individual has responsibilities to something beyond her own private will. Democracy’s emphasis upon the sovereignty of the individual, and the sanctity of individual freedom, can leave the impression that the democratic citizen has no such responsibility. But this is a misimpression. The democratic form demands that each citizen affirm a responsibility to respect what Kant calls the ‘dignity’ of every other, and recognize that this responsibility supersedes commitment to strictly individual interest.

Kant calls the ideal society organized along such lines the “Kingdom of Ends.”[3] In the Kantian Kingdom of Ends each member is, at once, the end for whom the society exists, the sovereign who issues the law of respect for each citizen as end, and the subject who dutifully abides by that law. We can immediately see that a society of tyrants, or those disposed to tyranny, cannot constitute a Kingdom of Ends, for in the Kingdom of Ends each must respect the freedom of each.

Thus, a Kingdom of Ends can only exist where each member willingly affirms the principle that respect for the dignity of the other must override the demands of private self-interest. Although Kant manages, through a logic that is anything but straightforward, to equate adherence to this principle with the exercise of individual freedom, the ‘freedom’ of which Kant speaks is at a far remove from what is generally understood by that term in popular culture. Kantian freedom is the freedom to do – not whatever one wants – but what is right. It is a freedom, thus, fully coincident with what to many might seem a morality imposed from without. That Kant is, nevertheless, able to speak of such morality as ‘autonomy’ and ‘freedom’ is due to his idealized conception of the rational person, who willingly affirms a greater duty to ‘right’ than to appetitive gratification, and who, thus, recognizes such duty as the highest expression of her own free will.

If we now compare Plato’s take on democracy with Kant’s we find that their differences lie, not so much in their conception of societal justice, as in their different estimations of the democratic citizen. For Plato, democracy, as a form, is inherently unstable; for its valorization of individual freedom yields a society in which everyone aspires to tyranny. For Kant, the democratic form implies a society in which each citizen recognizes, as the highest expression of his or her own freedom, respect for the freedom and dignity of every other. At the heart of their disagreement is a different estimation of the moral and intellectual potential of the average person. For Plato, only a moral and intellectual elite – the philosopher-kings – can be expected to rise above appetitive inclination to willingly prefer social justice to appetitive gratification. Kant, on the other hand, envisions, at least potentially, an entire society of such people; an entire society, so to speak, of philosopher-kings.

IV. Toward a Democratic Pedagogy

What all of this implies is that education – the right kind of education – is essential to the democratic form. Moreso than other political forms, democracy demands that its citizens embody a specific, and identifiable, set of moral and intellectual virtues; a set of virtues that do not arise spontaneously, but must be taught and cultivated. It is, thus, the educational establishment – not the press – that should be regarded as the ‘fourth estate’ of democracy. Without an educated citizenry the press itself will but pander to the appetites and sentiments of the general populace, as we increasingly see.

But it is not enough simply to laud the value of education, as is often done, we must say what kind of education is required. It must be an education that cultivates those intellectual and moral virtues integral to the democratic ideal itself – which, again, is not the ideal of individual freedom per se, but of respect for the freedom, and, hence, the person, of others. Democracy entails the belief that such respect – not the pursuit of appetitive gratification – is itself the highest expression of individual freedom.

To enact such a pedagogical program will require a major shift in the technocentric and market-oriented focus of our modern educational system; a shift, sad to say, in the opposite direction of that in which we have been trending for some time. The problem is that technology, by its very nature, is ethically neutral, and that the market culture of consumer-capitalism fills this ethical void with a continual stream of messages equating happiness with individual selfgratification. The confluence of these two trends – technologism on the one hand and consumerism on the other – has led to a conception of education that sees its principle purpose to be the imparting of technical skills for success in the marketplace, a marketplace largely driven by appetitive pursuits. If Plato’s analysis is at all sound, this does not bode well for the future of democracy.

What then is needed? Perhaps we can gain a general sense of this by recalling another passage from Plato’s writings.

In the Apology Plato has Socrates tell the famous story of his encounter with the Oracle at Delphi, whose designation of Socrates as the wisest man in Athens leads Socrates to interrogate the prominent citizens of Athens to see if he can find one wiser than he. After interrogating the craftsmen (technicians) of Athens, Socrates reports, “they did know many things of which I was ignorant, and in this they certainly were wiser than I was. But I observed that even the good artisans fell into the same error as the poets; because they were good workmen they thought that they also knew all sorts of high matters, and this defect in them overshadowed their wisdom.”[4]

By “high matters” Plato means the values that should govern private and public life. Our educational system has largely lost sight of the need to educate students in such “high matters.” If the above analysis is sound, the democratic form will not long survive such neglect.

What is required, beginning in the early years of high school, is an educational program that actively engages students in the dialectical practice of value inquiry, with the aim of imparting in them an understanding of the central role of values in guiding the conduct of private and public life. This, in turn, might then serve as the foundation for an extensive examination of those values integral to the democratic form itself. Only in this way may we have some hope of bringing these ‘high matters’ within the purview of the average citizen.

We thus arrive at a conclusion that will seem to some as outlandish as Plato’s seemed in his day: For democracy to survive and flourish we must make philosophy, specifically, a value-oriented philosophy, the heart of the public school curriculum. The challenge for those who would craft an educational program in support of the democratic form, is to consider how we might do so.

V. Conclusion: The Power of the People

To conclude, we might recall the ambiguity in the word ‘people’ with which we began. When we speak of democracy as ‘power of the people’ do we use the word ‘people’ in the plural or the singular sense? Our reflections indicate that the answer must be: both. Democracy, as a societal form, must be peopled by citizens who see concern for the dignity of others, and for the good of society as a whole, as integral to their own private good, such that private and public interest coincide. This requires a degree of moral and intellectual maturity that can only be achieved through a robust program of value-oriented, broadly ‘philosophical,’ education. The morally realized citizen-kings of Kant’s Kingdom of Ends can become such only as they approximate to the intellectually realized philosopher-kings of Plato’s Republic. A value-oriented pedagogy, thus, is essential to the democratic form as such. In the absence of such a pedagogy – to recall Plato’s words – “there will be no rest from ills of the city, nor, I think, for human kind.”

Richard Oxenberg received his Ph.D. in Philosophy from Emory University in 2002, with a concentration in Ethics and Philosophy of Religion. He currently teaches at Endicott College, in Beverly MA.

(A version of this article was originally published in Philosophy Now magazine, issue 111)

[1] Plato, The Republic of Plato, trans. Allan Bloom (Basic Books, 1968/1991), p. 240; 562b-c.

[2] Ibid., p. 153; 473d.

[3] For Kant’s discussion of the Kingdom of Ends see, Immanuel Kant, Groundwork of the Metaphysic of Morals, trans. H.J. Patton (New York: Harper & Row Publishers, 1964), pp. 100-103.

[4] Plato, Apology, trans. Benjamin Jowett in Selected Dialogues of Plato: The Benjamin Jowett Translations, editor Hayden Pellicia (Modern Library, 2001), p. 291; 22d-e.

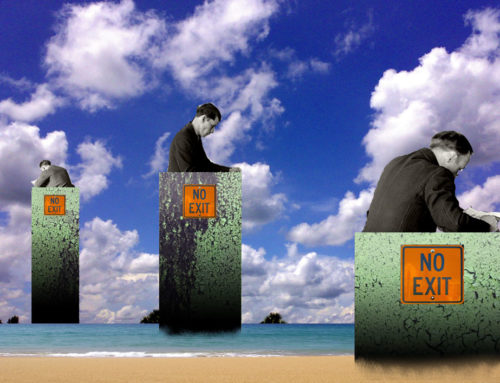

Image: The Nantucket School of Philosophy by Eastman Johnson, from the Walters Art Museum

Doesn’t Plato present the philosopher-king as more than just a bit of an enigma? Such a figure might present a solution to many political problems, but the burden of rule seems problematic for the figure itself. Why would the philosopher want to rule? How would it be in his interest to do so?

Actually, I noticed that a commenter on Facebook (Brent Colman) posted the following, which seems to be along the lines of my own concerns, so I’ll share it here:

” Not to be the stick in the mud, but the entire point of The Republic was 1) you can’t have a philosophically informed citizenry (myth of metals) as not every individual is, by their soul, capable of living a philosophical life and 2) The Philosopher King is a logical contradiction between nomos and physis, in that, a king must rule through the nomos, however, in so ruling through the nomos he violates his philosophical obligation of a life in accordance to physis.

Not saying it’s wrong, The Republic was just not a great basis for said argument…”

Granted that Plato might have been more disparaging of democracy than the American Founders (although, if I remember correctly, they were careful to make a distinction between the sort of representative republic they envisioned and popular rule), but isn’t a major point of this article almost painfully true at present: America needs a better educated electorate!

Hello Mike,

Thanks for your interesting comment and questions.

Plato’s own answer to why the Philosopher-King would wish to rule is that otherwise he (or she, Plato believed women could be Philosopher-Kings) might be subject to a less enlightened ruler. Thus it is in the Philosopher-Kings own self-interest to rule. And the Philosopher-King, being wise, would understand this.

That’s the explicit reason Plato gives in the Republic. There is, though, an implicit answer as well: The Philosopher-King, having seen and known “the good,” would derive satisfaction from serving it. I say that this is an “implicit” answer because, though Plato never says this in so many words, we see it in the figure of Socrates, who ultimately gives his life in service to “the god,” who (as the Apology tells us) has commanded him to seek to enlighten the citizens of Athens through his philosophical questioning.

And this, I think, gives us the answer to the second point Brent makes. I don’t think Plato believes there is a necessary contradiction between nomos and physis. The job of the Philosopher-King is not to enact an arbitrary ‘nomos,’ but to create laws and conventions in conformity with physis, i.e., “the good,” And, of course, this is just why the king must be a philosopher: Only the philosopher is truly dedicated to an understanding of the universal good.

As for the myth of the metals, I think you are absolutely right. Plato did not believe the average person capable of enlightened rule, which is why he did not believe in democracy. As I try to point out in my piece, Kant (and the Enlightenment in general) had a more hopeful and egalitarian view of human potential.

Was Kant right? Was Plato right? Can a citizenry govern itself in an enlightened manner, as Kant believed, or will democracy ultimately degenerate into tyranny, as Plato thought. I’m afraid we may be about to find out.

The basic point I wished to make, though, is that if democracy is to have any hope of saving itself from tyranny, it will need a philosophically-informed citizenry; by which I mean, a citizenry capable of rising above intensive self-interest to seek an understanding of the common good.

Thank you!

I enjoyed the article and thanks for your answers to my questions.

This is an excellent article!

I just wanted to point out a relevant exchange that I had some months ago in the comment section of a different article here at Political Animal Magazine : https://www.politicalanimalmagazine.com/socrates-made-tiny-and-cute/.

That exchange (easily one of the best I’ve ever had online) was between myself and Stefan Schindler, who has since written articles for the magazine. It deals in large part with the difference between a “good man” (the philosopher) and a “good citizen” (the patriot). While I learned a great deal from the exchange, I remain unconvinced that the virtues of these two human types coincide with one another. I am skeptical, to say the least, that we can equate what is good with what is noble.

My thoughts are similar after reading the present article. A healthy democracy might require a noble citizenry, or that some significant part of its citizenry be noble, but I’m not at all sure that is the same as a “philosophic” citizenry, or even a somewhat philosophic citizenry. It also seems to me that the kind of education required to produce the former would be very different from the latter. People devoted to the regime are not produced by an education that has philosophy at its heart. That doesn’t mean that their education should consist in mere indoctrination, especially in a democracy, but it is still something other than philosophy.

I’d like to hear more about what is meant by a “value-oriented pedagogy” in the context of this article. Which values? Whose values? The values of philosophy, “broadly” understood? America values? Liberal values? Conservative values? Catholic? Protestant? Jewish? Muslim? Kantian?

Hi Strkkon,

Thanks for your important question.

I have two things in mind when I speak of a “value-oriented pedagogy.” First, I am thinking of a pedagogy that engages students in value inquiry. Such a pedagogy does not teach one set of values over another, but has students consider the nature of values, their importance in personal and communal life, and how values might themselves be evaluated. Such value-inquiry, thus, is a philosophical practice.

Next, I would wish for students to specifically consider the values underlying the democratic form. As I say in my piece, there are certain values inherent to democracy as a political form, expressed, for instance, in the belief in universal natural rights.

My basic argument is that if democratic citizens are to preserve their democracy they must understand the values upon which it is based. This requires, first of all, an understanding of the importance and place of values in life in general, and, second of all, a reflection on the specific values that undergird democracy.

I hope that helps answer your question. Thanks again!

Hi Kevin,

Thanks for your thoughts. I’m pleased to hear that you appreciated your exchange with my good friend Stefan!

I’m not altogether sure just what you mean by ‘noble.’ To my mind “noble” implies a dedication, not just to a regime, but to what Plato would call “the good.” Of course it is possible (though dangerous) to be dedicated to the good without having a philosophical understanding of it. In the Republic, the class that might best correspond to this would be the Guardian-auxiliaries – the military class, who serve under the philosophers.

But such nobility of spirit is insufficient for the citizens of a democracy, precisely because it is the citizens who must be, not only dedicated to the regime, but its ultimate rulers. This means that they must not only wish to serve the good, but have some understanding of how to serve it. They must have, not only devotion, but wisdom.

Of course this assumes that there is a ‘good’ to serve, and that an understanding of it can be grasped, or at least approached, through (the right kind of) philosophical examination. I don’t defend that assumption in my piece, but I think the idea of democracy depends upon it.

If the noble can be directed toward the good, doesn’t that simply make it the good, or vice versa?

Plato seems at pains to make distinctions between these two things. The noble involves sacrifice for something outside of oneself or beyond oneself – sacrifice, that is, of ones own interest or good. This is the same difference as that between what is “right” (in the moral sense) and what is “good”.

The guardians of the city might be noble indeed, but their virtues are not the same as those of the philosopher. And the philosopher, at least as exemplified by Socrates, would appear to be concerned chiefly with what is good for him, not with some noble cause on behalf of the city.

That is my understanding of the matter, or a very brief version of it. And thank you so much for your reply. I will think about it more, and it was kind of you to make.

Thanks Kevin, for your response to my response.

Let’s pursue this a bit further. I’m not sure you’re quite grasping the character of Socrates as Plato presents him. Plato’s fullest statement about the character and mission of Socrates (who, for Plato, is the ideal philosopher) can be found in the Apology, where Socrates says:

“Men of Athens, I honor and love you, but I shall obey God rather than you, and while I have life and strength I shall never cease from the practice and teaching of philosophy, exhorting anyone whom I meet after my manner, and convincing him, saying: O my friend, why do you who are a citizen of the great and mighty and wise city of Athens, care so much about laying up the greatest amount of money and honor and reputation, and so little about wisdom and truth and the greatest improvement of the soul, which you never regard or heed at all? Are you not ashamed of this? And if the person with whom I am arguing says: Yes, but I do care; I do not depart or let him go at once; I interrogate and examine and cross-examine him, and if I think that he has no virtue, but only says that he has, I reproach him with undervaluing the greater, and overvaluing the less. And this I should say to everyone whom I meet, young and old, citizen and alien, but especially to the citizens, inasmuch as they are my brethren. For this is the command of God, as I would have you know; and I believe that to this day no greater good has ever happened in the state than my service to the God.”

These don’t sound like the words of someone concerned only with his own private good. Plato sees “the good” as a universal form. Its concrete application in the political sphere is “justice.” The true philosopher, as such, is dedicated to understanding “the good.” The *true* king, as such, is dedicated to implementing it politically. Plato’s point is that in order for a king to implement the good he or she must understand it. Hence, the true king must also be a true philosopher.

It is possible to have what we might call a “nobility of spirit” – i.e., a desire to serve the good, even a willingness to sacrifice oneself in service to the good – without understanding very well what the nature of the good is.

In the Republic Plato likens such people to guard dogs. The noble guard dog is selflessly devoted to his master, assuming (so to speak) the master to be worthy of such devotion. But, of course, the guard dog can be wrong about this. Plato takes such nobility of spirit to be the essential character-trait of the military person, who is selflessly dedicated to the regime, assuming it to be good (whether it is or not).

But if the society is to be well-governed the military person must be under the rule of the philosophical person. The (true) philosopher also has a nobility of spirit, but his/her allegiance is to the development of an understanding of the good itself, not to this or that regime.

Plato’s point, again, is that only the true philosopher can be a true king. My point is that in a democracy, since everyone must be (so to speak) ‘king,’ everyone must be trained in (the right kind of) philosophy as well.

To bring this down to earth a bit – among the frightening things going on as I write, is that we have a major candidate for President who does not seem to understand the democratic form itself. Should he be elected we can be fairly sure he will do it great damage. Such a thing is only possible in a country where a good part of the electorate doesn’t understand this form. You can’t maintain a democracy where a large segment of the people – the ‘demos’ – don’t understand what democracy is and entails. Other kinds of regimes do not depend on an enlightened citizenry, because the citizens don’t run the regime. But a democracy full of citizens who don’t understand democracy will inevitably cease to be a democracy. That’s the danger we face.

But, Mr. Oxenberg, isn’t the speech that you cite from The Apology as clear an example of Socratic Irony as there ever was?

Never mind that Socrates is there found addressing the city as a whole (or at least its representative citizens in the Assembly) – something that he has avoided doing during the whole course of his long life until that point, because his manner of speech and way of life is emphatically and explicitly unsuited to public affairs – but just consider what he actually says about piety and love of the city (patriotism).

The “God” that he refers to, and whose commands have been made known to him through the Oracle at Delphi, has given him a mission which amounts to little (or nothing) other than going around and TESTING what the God has said, according to the powers of Socrates’ own reason. And Socrates “daimon”, the other manifestation of the divne, or semi-divine, in the dialogue, is a voice in his head that basically counsels him continuously AGAINST involvement in public affairs and politics, for the sake of his own good.

I think the speech is amazing, and hilarious, but I think it problematizes the relationship between the noble and the good, in a radical way.

There is also the problem of what good we are talking about. Or, rather, who’s good. Unless the good of the regime is identical to the good of a given individual, there will be conflicts between them. This is were nobility comes into play – it is exhibited in individuals who are prepared to sacrifice their own good for the good of some larger whole. Socrates seems entirely disinclined from making such sacrifices, although not because he seeks to harm the city for his own interest. He seems quite gentle for the most part, and generally inclined to do his own thing, as it were, but he is not willing to put the interests of the city over his own.

Now I agree with you that there is a problem when it comes to democracies – citizens must somehow be both devoted to the regime and not so devoted at once. This is a grave difficulty, and it seems like the attachment to the permissiveness and licentiousness of democracies will often trump (no pun intended) the felt need for enlightenment amongst the citizens. So I agree with you too that some kind of education is required, a difficult and always unstable education, which breeds citizens devoted to liberal ideals. We must have Americans who both love America and who are capable to a rather high degree of being critical to America. But liberalism is politics, not philosophy, and political enlightenment seeks the widespread rationalization of men, not to cultivate the philosophic life amongst them.

I agree with you yet again that we face grave dangers. But these are not summed up by an unsavory presidential candidate that shall here remain (mostly) nameless. These dangers are pervasive in our society, they extend to the foundations of our regime, its principles, people, and government. The dangers do not just express themselves in various particular administrations, candidates, or movements, and they are, ironically, I suppose, given oft-heard demands for bi-partisanship, very much just that – bi-partisan.

Kevin – it seems we have a different interpretation of this passage, and of Plato’s presentation of Socrates. No, I don’t think this speech is at all intended as irony, though Plato, great writer that he is, often embellishes even his serious points with an ironic twist.

The god sets Socrates out on a mission to try to discover wisdom in Athens (this is what Socrates’ testing of the god’s pronouncement amounts to). If we recall Plato’s overall epistemology, this is just how wisdom is achieved, through dis-covery (anamnesis). So Socrates’ effort to dis-cover (uncover) wisdom among the Athenian citizens is, at the same time, an effort to impart it.

I think Socrates understands that this is what he is doing, and understands as well that he is doing it for benefit of the citizens and in service to the god of wisdom ( who is, himself, in service to “the good.”) For Socrates and Plato there is a devotional element to the philosophic life. It is not a mere exercise in intellectual amusement.

Socrates cannot engage in political life in Athens, not because he doesn’t care about the good of the society, but because, given its current state of corruption, he would not be able to survive in public life. But Plato would not have written the Republic – nor, later, the Laws – if he did not consider it important for philosopher’s to contribute in the political sphere.

But we are agreed that our society faces grave dangers. Whether I would agree that these dangers “extend to the foundation of our regime, its principles, people, and government,” would depend on just what you mean by this. I don’t think the problem lies in constitutional democracy as such, nor in the principle of natural rights on which it is founded. But it does lie in a paradox that I try to express in my piece – that in order for democracy to work the individual, qua individual, must come to regard some degree of devotion to the common good as essential to his or her own individual happiness. That’s the only way for freedom and morality to coincide. That’s what is required for the Kantian “Kingdom of Ends.” And that convergence of individual and universal good is something (I’m convinced) Plato believed the *true* philosopher understands and strives to lives by.

How do you define ‘reason?’

How do you ask a question?

Hi Robert,

I can give you what I would consider to be Plato’s definition: reason is that faculty through which we acquire an understanding of the good order of things (ourselves and the world).

Of course there is much more to say than that, including that the human rational faculty is imperfect, and that we must employ reason to understand reason itself, which complicates things.

But that definition might serve as a beginning.

My view is that philosophy needs to be ingrained in law making to some extent, however, maybe we should not rely on the masses to get up to speed in being able to philosophize.

I think a rather good solution to this would be to create a section of government that resembles Plato’s philosopher kings. This would require more voter initiatives like California. It would work by the voters voting on a law they have proposed, and, if passed, then the philosophy section of the government would hyper-analyze the law.

The philosophy section of the government could hyper-analyze the law and ensure that it would not hinder anyone’s freedoms and that it upheld good morality, depending on what morality the philosophy section has prescribed to.

This may be an attack on democracy, as not all laws that the majority voted for would come to fruition, however, it may lead to more fair laws, and better laws for society.

Right… so you want to dismantle the Republic and set up some kind of aristocracy?

This is splendid: exhilarating in its coherence and compelling in it’s immediacy. Suddenly we live in dilemmas that gave us Socrates’ reflections and we seem headed for the uncertainty of Hobbes’ era.

We’re seeing the travails of governance and participation in a time of polarisation, weaponized narrative, fake news and the rapid retreat from reason on a global scale. Technologism and consumerism have produced a symbiotic attention economy that further erodes opportunity for public reasoning.