By: Stefan Schindler

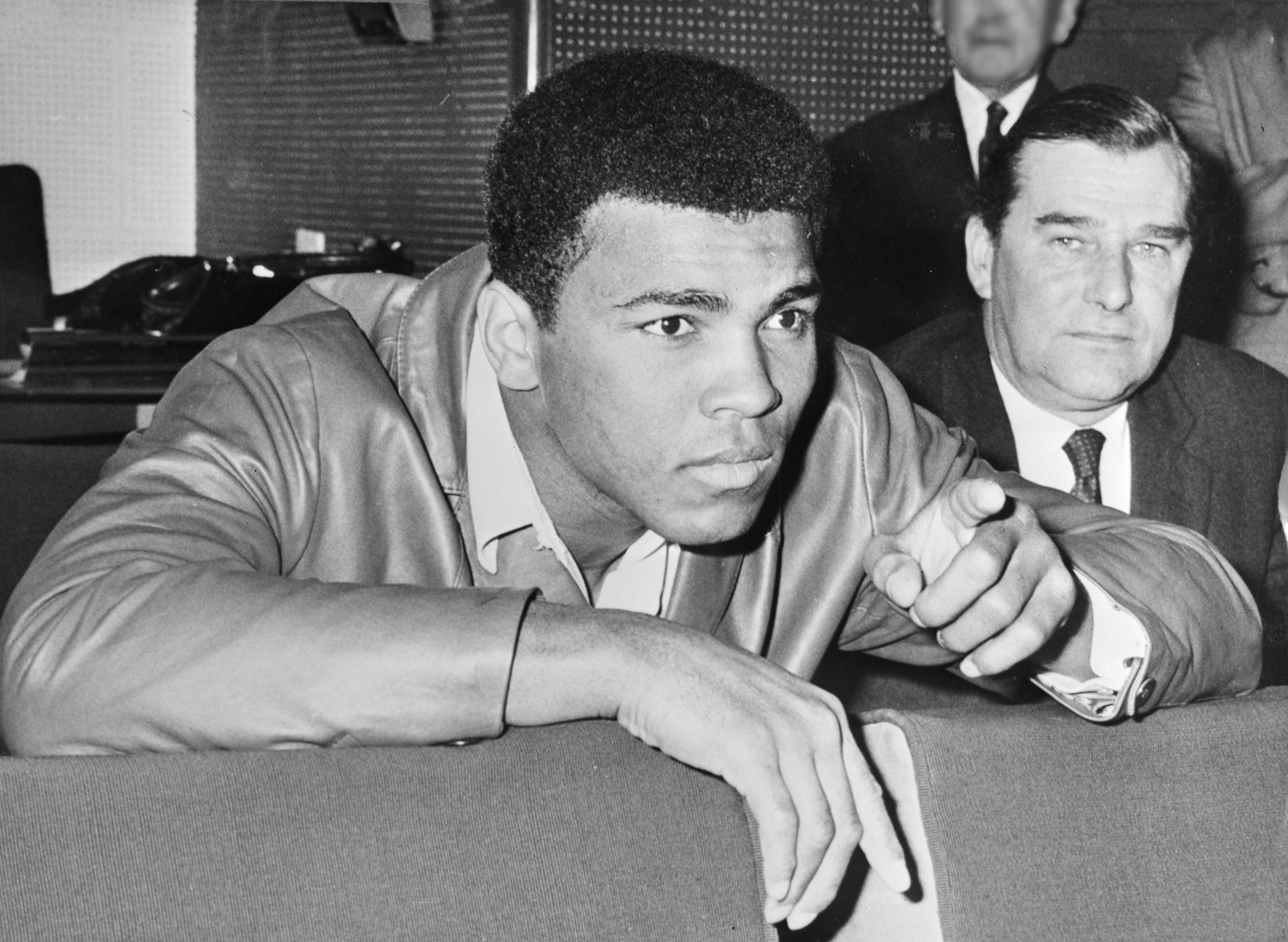

Muhammad Ali died on June 3rd, 2016, at the age of 74. Unsurprisingly, the media has been flooded with articles celebrating history’s most famous boxing champion. But Muhammad Ali was more than just king of the ring. He was a political figure with enormous influence. Too many people today, perhaps especially young people, are unaware of this important fact. It is a fact worth recalling. The social conflicts informing the revolutionary turbulence of the 1960s are still with us, and in some ways are more extreme now than they were then.

It is appropriate, therefore, to take another look at Ali’s life, and to note the inextricable intertwine of his boxing fame and his political impact. Mike Marqusee’s book on Ali – Redemption Song: Muhammad Ali and The Spirit of The Sixties (Verso; 1999) – acts as an excellent guide. It reminds us that we still have a long way to go in achieving social justice, and that the socio-political battles of the Sixties are far from over. Marqusee’s opening paragraph is astute and provocative:

“A strange fate befell Muhammad Ali in the 1990s. The man who had defied the American establishment was taken into its bosom. There he was lavished with an affection which had been strikingly absent thirty years before, when for several years he reigned unchallenged as the most reviled figure in the history of American sports.”

Marqusee begins his exploration of Ali’s life by pointing to a moral conundrum. Muhammad Ali was finally embraced by a culture he once defied. Why did Ali accept the embrace? It contradicts his own redemption tale and the spirit of the sixties. The Ali story thus ends in tragic irony. Of course, it would not be so poignant if the hero had not been so incandescent.

There are three redemption tales in the life of Muhammad Ali: existential, athletic, and osmotic. The first two are authentic and inspiring. The third is cautionary and disheartening.

The existential tells a story of self-redemption starting in 1964, a radical recreation of self in the crucible of history. In the next few years, threatened with jail and stripped of his passport and boxing title, Ali looked in the inward mirror, saw Allah, and defied American culture and President Johnson’s war machine.

Cast as an outlaw in the land of his birth, Ali became a voice heard round the world; a shooting star across the planet; a beacon for the universal struggle for human rights.

The second redemption story, the athletic, climaxed in “the rumble in the jungle” in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) in 1974. Ali fulfilled the quest to reclaim the title that once was his: heavyweight boxing champion of the world. His crown had been taken from him, and Ali’s odyssey to the title fight had about it the mythic glow of the return of the king. Ali had said, “I am the greatest.” He intended to prove it; and he did.

The third redemption story illustrates the power of cultural osmosis. Marqusee refers to it in the opening paragraphs of his book. In this story, Ali’s transformation from outcast to hero is embodied in his guest-of-honor appearance at the opening ceremony of the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta. Despite his paralyzing illness, Ali raised a trembling arm and ignited the 170-foot wire fuse leading to the Olympic cauldron above the stadium. Marqusee captures the irony of the moment: “It was because of the gap between Olympic ideals and American realities that, thirty-six years earlier, Cassius Clay had flung his gold medal into the Ohio River.”

In 1996, was the gap between Olympic ideals and American realities any less wide than in 1960? Any less deep, schizophrenic, or oppressive? In some ways, yes; major battles for justice had been won. The Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the ending of The Vietnam War in 1975. But the cost was staggering; and despite battles won, the war of the haves against the have-nots had continued unabated, punishing both America and the globe.

Marqusee takes his title, “Redemption Song,” from a Bob Marley tune. Ali’s life lends itself to being read like a ballad of redemption. But if there are really three redemption stories in the telling of the tale of Muhammad Ali – roughly coinciding with 1964, 1974, and the 1990s – we need to be wary of which song is being sung.

The Ali who visited the United Nations in March 1964 with Malcolm X, announcing his upcoming trip to Africa, is far indeed from the Ali of the nineties, appearing in commercials for pension plans, lighting an Olympic flame for Coca Cola, and ringing a ceremonial gong at the New York Stock Exchange to help inaugurate a new millennium.

In the sixties, Ali’s personal struggle for justice against the corporate national security state perfectly mirrored the transformative spirit of the times: the ever-multiplying cries of protest against a violent and absurd world order. Condemned by America, yet a hero to millions around the globe – Ali was never so heroic as when he was outcast. When we find him, thirty years later, ringing a bell for Wall Street, we have to wonder: Who is being redeemed here? Whose interests are being served? At what cost? Isn’t this simply another example of the establishment’s success in swallowing up even some of its most defiant challengers?

Marqusee takes the reader through the first and second redemptions with graceful and illuminating storytelling. Ali and his times were intense. In his David-against-Goliath battle with Uncle Sam, Ali was a luminous presence on the world stage, a vocal and forceful example of courage of conscience.

Athletically, Ali redeemed himself a decade later in the ring, defeating George Foreman in the heart of Africa for the heavyweight boxing title. Ali had already been through so much. Could he do the impossible again? Defy history? Make history? George Foreman looked like King Kong in the ring. Ali was no longer at the peak of his boxing skills. Although Ali was just as tall as Foreman, and even though his longer arms gave him a crucial advantage, Ali could get seriously hurt, possibly killed. Even people in Foreman’s camp worried about it. Ali was the underdog; and once again, he looked in the inward mirror, saw Allah, and went forth to stun the multitudes. Ali was loved in Africa, and his victory cheered the hearts of the oppressed.

It is the third, pseudo-redemption that gives us pause, and Marqusee both opens and closes his book by pointing to it. He doesn’t judge. He tells the story, then leaves the reader with an ethical itch. Ali in the nineties lent the power of his celebrity to the corporate interests he once famously defied. This is a tragic flaw. Ali’s actions were not merely paradoxical or whimsical; they contradicted his former clarity, bravery and consistency.

Ali’s third “redemption” is a power-elite make-over myth; outcast hero ‘welcome home, come in from the cold;’ a Faustian bargain.

Marqusee for the most part lets the reader figure this out; and I can’t decide if that’s a flaw or a virtue. Perhaps it’s both.

Because he titles his book “Redemption Song,” Marqusee would seem to be obliged to keep his “redemptions” straight, and to emphasize more vigorously the moral anticlimax which ends the ballad of Muhammad Ali. Ali as shill for Wall Street is not a “redemption song” which the people’s movement needs to sing.

Still, Marqusee’s subtitle, “Muhammad Ali and the Spirit of the Sixties,” informs us that the song he will write about is the man Ali in the spirit of his times. Marqusee shows Ali as both mirror and inspiration to the spirit of protest that marked the age. The redemption song he describes is not just Ali’s; it is the son of the Zeitgeist. Marqusee narrates the history of the sixties like a balladeer, and the reader is carried into a cascade of events: the wild rhythm of a decade of tempest.

The incandescence of Muhammad Ali was planetary in scope. He belonged to the world, not to America. Marqusee, an American sportswriter living in England since 1971, provides a transatlantic view: “In the name of wider and higher loyalties [Ali] refused to serve America in a time of war and as a result was threatened with prison, barred from practicing his trade, harassed by his government and condemned by his country’s media. At the same time, the very actions that so enraged the defenders of ‘Americanism’ made Ali a symbol of anti-American defiance and quest for autonomy across much of Africa, Asia, Latin America and the world.”

For many years Ali was faithful to those “wider and higher loyalties” which the defenders of Americanism found so distasteful: evocation of black dignity; empathy with colonized people around the globe; conscientious objection to war; a Malcolm X-like in-your-face challenge to white supremacy and defacto segregation.

Ali was a hero to millions less for his boxing skills than for his awesome contest with American militarism, racism and economic apartheid. When he joined the Nation of Islam and changed his name from Cassius Clay to Muhammad Ali, he also defied America’s boxing establishment, sports culture in general, and America’s long history of Judeo-Christian hypocrisy. It was as if Jehovah’s “irresistible force” had met Allah’s “immovable point.”

Ali’s determination to speak the truth and act his conscience came partly from his friendship with Malcolm X. One of the great virtues of Marqusee’s book is that he brings this friendship to light, traces its history, and shows how important Malcolm was in the evolution of Ali’s ideals.

Ali’s prowess in the ring was a function of his gifts, physical and mental; he out-fought most of his opponents partly because he also out-thought them. But where did he get the courage to fight his battles outside the ring? Malcolm’s tutelage, Marqusee argues, goes a long way toward answering that question. Marqusee’s book tells us a lot not only about Ali and Malcolm, but also about Bob Dylan, American foreign policy, world events, and the revolutionary spirit of the sixties.

For example, he introduces Kwame Nkrumah, who lived and studied in America and England, then “in 1947 returned to the Gold Coast. Declaring that ‘freedom is not something one people can bestow on another as a gift,’ he launched the decade-long political insurgency that would make Ghana Africa’s first independent, post-colonial state.” In the late ‘50s, “the new Africa came to Harlem, to black America, living and breathing fire – in the persons of Nkrumah and above all Patrice Lumumba.” Nkrumah returned to Ghana to try to steer his country on a nonaligned path between capitalism and communism. Lumumba, another popular leader of a people’s aspirations, returned to the Congo, where he was hunted down and assassinated with the help of “CIA operatives and Belgian and British mercenaries.”

Because the issues of the sixties are still with us – racism, covert operations, war, national and global economic apartheid – Marqusee’s book is still timely. It will be especially enlightening for those who think that Martin Luther King Jr. only had a dream. It may also inspire those who lived through the sixties: recalling sacrifices made, victories won, unfinished work.

Mercurial, poetic, paradoxical and beautiful, Ali transcended any single attempt to capture his fullness. Books and movies abound, giving first one glimpse, then another. Why then yet another book on Muhammad Ali? His story – dramatically entwined with history – is, of course, irresistibly seductive, but it often overwhelms the story of his times. The virtue of Marqusee’s book is that he rights the balance and offers a wider picture.

On the morning after winning the heavyweight boxing title from Sonny Liston in early 1964, Ali confirmed his allegiance, not to America, but to the Nation of Islam, saying, “I don’t have to be what you want me to be.” Marqusee takes this assertion as the Ariadne’s thread of Ali’s life, the golden strand of continuity through the turbulent history about to unfold.

“I don’t have to be what you want me to be. I’m free to be what I want.” With these words Cassisus Clay voiced the defiant spirit of the sixties. Like “chimes of freedom flashing” in a Dylan song, Clay’s existential revolt bridged the personal and political. The following day he said, “A rooster crows only when it sees the light. Put him in the dark and he’ll never crow. I have seen the light and I’m crowing.”

Reactions from the media were “swift and hostile,” says Marqusee, including a comment from former holder of the heavyweight boxing title Floyd Patterson that he’d fight Ali for free “just to get the title away from the Black Muslims.” But others saw a champion human being inside the new boxing champ. Jackie Robinson – the first black athlete to play major league baseball in the 20th century, signing with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947 – declared that “Clay has as much right to ally himself with the Muslim religion as anyone else has to be Protestant or Catholic.” Leroi Jones – black activist, poet, playwright, and music critic – perceived that “Clay is not a fake, even his blustering and playground poetry are valid; they demonstrate that a new and more complicated generation has moved onto the scene.”

Muhammad Ali had just sailed into a Shakespearean tempest. Despite scattered support, his life would henceforth be a storm. It would embody and reflect the wars of the sixties. Marqusee notes that “as a young challenger [Ali] had been brash and bold, an entertaining eccentric; within hours of winning the championship he had metamorphosed into an alien menace. He dared to turn his back on America, Christianity and the white race. Many black men had been lynched for less.”

Fortunately, Marqusee is not only a sportswriter but also an astute observer of human behavior. Ali’s life was linked to the culture of sports, and thus to group psychology. What is it, Marqusee wonders, that enables a sporting event – competition between two or more individuals – to enthuse, enthrall, even obsess multitudes? He quotes Jerry Seinfeld: “People come back from the game yelling, “We won! We Won!” No: They won; you watched.” Despite the empirically obvious, people identify with their heroes in the arena, and often hate their opponents.

The adventure of sport releases collective psychological furies, allowing individuals to project emotional and psychic forces into the drama. The drama then unfolds back into them, creating ecstasy or despair.

Practiced in the Oval Office and the Pentagon – and supported by Wall Street and America’s mainstream news media – mistaking symbols for reality would unleash President Johnson’s holocaust in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, further perpetrated by the war crimes of President Nixon and Henry Kissinger.

The South Vietnamese National Liberation Front and the North Vietnamese Army – with, of course, the overwhelming support of the people – out-thought America’s military planners, and thus out-fought them. Time was on their side. This simple truth was also reflected in Ali’s 1974 victory over George Foreman. Ali’s survival depended on cunning. Ali went rope-a-dope in the second round, and for the next thirty minutes – apart from the exciting last thirty seconds of round five – he allowed Foreman to exhaust himself pounding away on Ali’s body. Shortly into round eight, when the moment was ripe, Ali sprang from the ropes and knocked Foreman to the floor, decisively regaining his world heavyweight boxing title.

Nine years earlier, on March 4, 1965, high on the northern coast of South Vietnam curving into the South China Sea, two battalions of American marines disembarked at Danang. The Vietnam War that President Johnson had promised the American people he would not wage unfolded into ten years of Apocalypse Now. The tentacles of the American war machine would grasp a generation of mostly underclass American youth and throw them into the Indochina cauldron. Those tentacles would reach for Muhammad Ali. The Vietnam War, said Stokely Carmichael, was “white people sending black people to kill yellow people in order to defend land they stole from red people.” At the cost of his title and threatened with imprisonment, Ali successfully challenged the American government, contributing his immense prestige to a movement that helped bring an end to The Vietnam War.

In time, Ali would be used for commercial profit. But consider: in pursuit of a boxing career at an early age, Cassius Clay found a culturally acceptable role for the release of his awesome talents. Perhaps therein he also found a warped avenue for his gifts; and despite his gentle, comic and gregarious nature outside the ring, he learned to excel at a life of violence, and thus be at moral odds with his life as a peacemaker. The practice of pummeling one’s opponent into submission has far more in common with American imperialism than with the transformative movement for peace and justice that was the heart and spirit of the sixties.

We are each to some extent pummeled every day by the morally obscene and absurd world in which we live and move and have our being. Ali, too, was molded by the cultural hegemony of American capitalism – worked on by his circumstances. And, in Camus’ best sense, he remained a rebel. Ali appeared on television to call for the eradication of third-world debt, serving as a voice for Michael Parenti’s observation: “Third-world nations are not under-developed; they’re over-exploited.”

In 1994, at The Peace Abbey in Sherborn, Massachusetts – having just received The Peace Abbey Courage of Conscience Award – Ali unveiled The World Memorial for Unknown Civilians Killed in War, reminding those gathered that nine out of ten casualties in modern war are civilians, and half of these are children.

The day after Ali died, Bob Dylan offered this appraisal: “If the measure of greatness is to gladden the heart of every human being on the face of the earth, then he truly was the greatest. In every way he was the bravest, the kindest and most excellent of men.”

Dylan’s comment on Ali echoes Plato’s encomium to Socrates at the end of The Phaedo: “Of all those we have known, [he was] the best, and also the wisest and the most upright.” It should come as no surprise that Dylan echoes Plato; after all, Dylan has long been America’s most political and philosophic rock’n’roll poet.

The difference between Ali and, to borrow Marqusee’s description, “a craven servant of white power” like Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, is, as Mark Twain would say, the difference between lightning and a lightning bug. Marqusee’s book reminds us of the battles of the sixties; what they meant, why they’re important, and why they still need fighting.

Marqusee’s book on the life and times of Muhammad Ali journeys into the smoldering fissures that still inform our collective psyche: globalized, militarized, manipulated, impoverished, terror-edged, spied upon, and led by lunatics. In his follow-up book on Bob Dylan, Marqusee makes exactly the right point when he suggests that Ali’s turbulent life, “the politics of Bob Dylan’s art,” and the revolutionary tempest of the sixties “might someday come to seem merely an early skirmish in a conflict whose dimensions we have yet to grasp.” As William Faulkner said: “The past is not dead. It’s not even past.”

A version of this book review was first published in Socialism and Democracy – the journal of the Research Group on Socialism and Democracy – Vol. 14, No. 1, Spring-Summer 2000. It has been modestly updated for reappearance in 2016. Special thanks to Victor Wallace – professor of Political Science at Berklee College of Music in Boston, and current editor-in-chief at Socialism and Democracy – for his editorial help in multiple drafts of this review.

Mike Marqusee died in 2015. In 2003, four years after his book on Muhammad Ali, Marqusee published Chimes of Freedom: The Politics of Bob Dylan’s Art (rereleased in 2005 as Wicked Messenger). Look for the reappearance of Dr. Schindler’s review of Chimes of Freedom (originally in Socialism and Democracy, 2004) in an upcoming issue of Political Animal this fall.

Image: Muhammad Ali in 1966, from the Dutch National Archives, distributed under CC BY-SA 3.0 nl

The children of the 60s are, in large part, the establishment today. And the progressive left today is not the same as it was almost 50 years ago. Perhaps Ali’s attitude toward the establishment changed over time, but the establishment itself changed even more.

Roughly speaking, the children of the ’60s divide into two camps: those who participated in the peace and justice movement for a more sane and egalitarian world, and those who didn’t. The former got the headlines — and the teargas and head-bashing, while their leaders (JFK, MLK, RFK, John Lennon, etc.) were systematically killed — while the latter largely jumped aboard the Reagan counterrevolution and became today’s establishment. You quite rightly note that the progressive left is not the same as it was 50 years ago. It’s now a scattered, fractured, mostly underground movement, occasionally achieving popular voice through, for example, the Occupy protest against Wall St., and the likes of Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders. Meanwhile, I’d argue that the establishment — far from having “changed even more” — is pretty much the same old national security state we inherited from Truman, but now with an even more frightening consolidation of power, conjoined to an ever more Faustian subservience to corporate influence.

I really liked this article and Marqusee’s book sounds worth reading. I appreciated the attempt to actually evaluate what became of Ali in terms of what he had stood for earlier in his life. I think there should be more honest and intelligent treatments of the subject, along the lines of this one. But I did feel a little disappointment when ideologically charged political views were inserted, such as the following: “President Johnson’s holocaust in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, further perpetrated by the war crimes of President Nixon and Henry Kissinger”. It is not that the events in South East Asia which this refers to could not in anyway be regarded as a “holocaust” or that Nixon and Kissinger are necessarily above the accusation that they were war criminals, but those are highly contentious claims, and they weren’t substantiated here. Beyond that, I really liked it.

What you call “ideologically charged political views” might be simple historical facts. There wasn’t room in the article to substantiate the war crimes of Johnson and Nixon, but they are easily verified. For a quick but comprehensive summary, see my book AMERICA’S INDOCHINA HOLOCAUST: THE HISTORY AND GLOBAL MATRIX OF THE VIETNAM WAR.

“It was as if Jehovah’s “irresistible force” had met Allah’s “immovable point.””

Is this really emblematic of the spirit of the 60s? The 60s saw people breaking down traditional modes and orders. Perhaps Islam could have been one of the things used to break them down, but didn’t it represent an even more traditional order than the ones (the author refers to “Judeo-Christian hypocrisy”) that it would have been used to combat?

It makes you wonder what Ali really stood for or understood even at the outset.

I’d say that “what Ali really stood for” was quite simple. He embodied Courage of Conscience, even if he wasn’t always consistent. Meanwhile, you are quite right to imply that Ali did not understand, especially at the outset, the nature of The Nation of Islam, nor the Islamic religion itself (with its multiple and complex facets). And you are equally right to imply that Islam can be just as provincial, traditional, regressive and hypocritical as many so-called practitioners of the Judeo-Christian ethic, even as its more enlightened and progressive voices lend support to interfaith harmony and a more peaceful and egalitarian world community. Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali both evolved into the latter, becoming icons for moral common sense and universal brother-sisterhood.