A conversation between the Editors of Political Animal and a doctoral candidate in clinical psychology about the misuse of the term “triggered”, its cultural context, and implications.

The term “triggered” has shot into the mainstream in recent years. From Tumblr blogs warning their readers about possible triggers in subjects as varied as rape, death, and slimy things, to university students calling for trigger warnings on F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby due to its portrayal of misogyny and physical abuse, the language of triggering has entered the global consciousness.

Originally conceived by clinicians dealing with “shell-shocked” soldiers in WWI, “trauma triggers” are experiences (situations, sounds, places, etc.) that cause someone to recall a previous traumatic memory. This technical usage expanded as post-traumatic stress disorder became better understood in the late 20th century.

Now being “triggered” has broken free of its clinical origins and is widely used online and in classrooms, often in contexts that have little to do with the idea of recalling a previous trauma. Perhaps unsurprisingly, as the term entered popular usage, it also became divorced from its technical roots.

What is more surprising is that the popular usage of triggered has circled back to clinical psychology, and is beginning to distort the technical meaning of the term in the field where it originated.

This article is a back and forth between the editors of PA and a clinical psychology doctoral candidate about how they see the term triggering being misused in their practice. Since this article is partly a rant about colleagues, we’re going to call this person MOTIMT (misuse of triggering is my trigger).

Political Animal: So, you’re saying that misuse of triggering isn’t just a pop phenomenon, but it’s also being misused in the clinical setting?

MOTIMT: Yes! In my experience, the meaning of the term trigger is definitely getting lost within the psychology community. Clinicians use the word trigger frequently, fervently, and as far as I can tell, completely incorrectly.

“I just find this mother so triggering” a clinician once said to me about a client’s mother who had Borderline Personality Disorder. She looked so serious that I felt guilty that my first reaction was that I wasn’t even sure if she had finished her sentence. “Triggering of what?” I’d wondered. Then I thought “wait a minute, is this how you’re choosing to tell me that your own mother also has Borderline Personality Disorder?” I prepared a concerned face and follow-up questions as she lightly moved on to other topics. It was clear that her mother did not have Borderline Personality Disorder.

PA: What do you think she actually meant?

MOTIMT: Well, I’m not 100% sure, but I think she just meant she didn’t like her. After that incident, I started to notice a pattern. My fellow clinicians were often labelling situations as “triggering”. When their personal disclosures never followed, it became evident that they weren’t using the word “triggering” to describe reminders of challenging events that they had personally experienced. Instead, they were using it to describe clients that they found particularly unlikeable or difficult to work with.

PA: So what’s the proper use of the term?

MOTIMT: The term “trigger” actually comes from the literature on post-traumatic stress disorder where it refers to a reminder of a traumatic event that one has experienced. So clinicians should only talk about being triggered by a patient if they have had some sort of traumatic experience that the patient or patient’s experience is reminding them of. In that case, they absolutely should use the word; it could have a powerful therapeutic impact. But if not, they should express their understanding in other ways.

PA: Why is this important? After all, words change their meaning all the time. Why should we view this as a case of incorrect usage, rather than expanding the usage of the term?

MOTIMT: Well, this incorrect usage of the term “trigger” undermines its true meaning in potentially harmful ways. When clinicians imply that they’ve personally experienced a traumatic event which they haven’t, it takes something away from their clients who have actually experienced it. That’s a very important difference that gets lost if you try to broaden the meaning of the term.

In my more cynical moods, I think that clinicians like using this phrase because it sounds so emotionally intelligent and indisputable. But I really think that they do it because of the heavy emphasis on first-hand experience in Psychology.

Empathy is one of the most highly valued traits in a therapist. Empathy used to be defined as understanding someone else’s situation because you’d been in the same one, as opposed to sympathy which was defined as feeling sorry for someone else’s situation without a deep understanding of it. However, increasingly, and particularly within Psychology, empathy is starting to mean having the ability to vicariously experience someone else’s experiences.

PA: That’s really interesting. With both empathy and triggering, you’ve got a clinical term that originally referred to a highly-subjective personal experience. And now people are using it as a stand-in for more general feelings or opinions, even in the field of clinical psychology.

Although it might sound scientific to say that a client you don’t like is triggering, it’s really just a moral judgment disguised in the language of medicine. This is something Nietzsche called out frequently—in Beyond Good and Evil he famously refers to Spinoza’s Ethics as a “hocus-pocus of mathematical form” designed to mask the author’s personal opinions, and suggests that physicists are reading their democratic biases into nature when they describe it in terms of laws rather than tyranny. For Nietzsche, these misuses of language provided a way to draw out the deeper, often unexamined, perspective of the speaker.

Do you think this expansion of the meanings of empathy and triggering is part of a wider shift in the way people in your field are thinking about what it means to experience something?

MOTIMT: Yes, there may be something to that. There definitely is a move towards recognizing vicarious experience as similar to first-hand experience.

Look at how the meaning of PTSD has been expanded in the latest version of the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders). One of the main criteria for PTSD used to be having had first-hand experience of a trauma. But in the most recent version (DSM-5) the definition of PTSD was changed to explicitly include vicarious traumatization. In the previous version (DSM-IV-TR) PTSD required experiencing, witnessing, or otherwise being confronted by a traumatic event. Now this has been widened to include learning about a traumatic event that occurred to a close relative or friend, or even just being repeatedly told about it in a professional setting. In other words, if I hear that my brother was stabbed, I can get PTSD. Or if my client is abused and repeatedly tells me about it I can get PTSD.

This is weird. It’s almost like PTSD is something you can catch now.

PA: Especially if you’re a clinician – we non-professionals apparently are only empathic enough to catch PTSD from close friends and relatives.

MOTIMT: I know! It’s almost like empathy is patented! It sometimes feels like clinicians are trying to restrict normal human feelings to their profession.

PA: It certainly does seem like all these shifts in language that we’re discussing are blurring the lines between clinical judgment and personal feeling.

As you said earlier, MOTIMT, there’s a certain indisputability to first-hand experience. So it’s understandable why clinicians might want to couch their professional opinions in the language of empathy or personal experience. But when you treat the clinician’s indirect experience as on par with that person who actually experienced the event, you undermine the idea that the clinician is a detached impartial observer. Which, in turn, calls into question the scientific nature of what the clinician is doing.

In that respect, this hollowing-out of clinical terminology seems to fit within the wider postmodern rejection of objective or rational standards in favor of the personal and subjective. It’s a way of acquiring a sort of authority equivalent to science for personal experience. It reminds me of how the term philosophy has become diluted in contemporary usage. What once meant a comprehensive way of life oriented around the love of wisdom is now a loosy-goosey shorthand for anything anyone holds to be true.

MOTIMT: Once you start misusing terms it’s a slippery slope!

In fact, I have a horrible confession to make—ever since we first spoke about doing an article on the term triggered, I’ve found myself starting to using the word. And now I can’t even tell if it’s ironic or not. It’s like OMG: you start saying it as a joke but quickly find yourself using it for real.

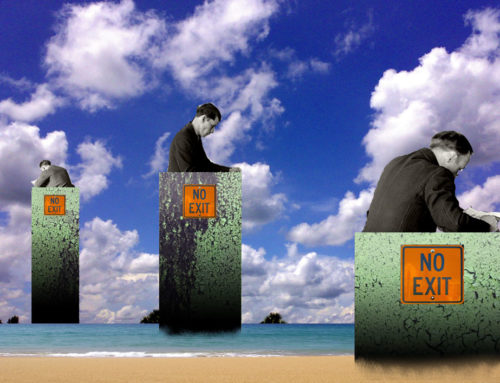

Image from the Family Inequality blog.

I think this person’s perspective isn’t practical. Not only can you not know whether the clinician may have experienced something similar to what a patient has disclosed and therefore been triggered (in the true sense of the term), but to be so fixated on the use of this word detracts from understanding what someone is trying to communicate.

Perhaps a clinician finds a patient hard to work with or unlikable because the person has characteristics or interpersonal patterns that are the same as a difficult person in their personal life. In that sense while not a PTSD severity trauma, the term is referencing the person’s own difficult experience from their past that the patient is resurfacing. None the less I think it’s not a practical positron, it’s focusing on the misuse of the term instead of truly trying to understand what’s trying to be communicated.

Do you think that the widespread misuse of terms related to mental health should just be ignored in case not every incident is actually a misuse? Would that be a more practical position?

A clinician is a professional. A professional who is trained to work with the mentally challenged and the mentally ill. If a professional cannot use the correct terminology to described their feelings and or their experience with a patient, then this raises a concern.

A professional is also supposed to be unbiased and not allow their personal feelings to get in the way of giving professional help and guidance to a patient.

If a professional misuses a word, then how can we be certain they are not misdiagnosing patients based on their biases and/or based on their “triggered” feelings.

I have a sister who is bi-polar paranoid schizophrenic, it would be heart-breaking to learn a “triggered” professional clinician misdiagnosed her because of their lack of professionalism.

I work in a service that repeatedly uses this term, “triggered”, and then offers its comforts to people in crisis looking for a hook to hang their excuses on. This may sound cynical, but I’m completely serious. For example, Someone with a borderline personality disorder is asked, are you triggered by the way that person smells like alcohol? of course the client is going to say yes, it offers them immediate sympathy and a way out of future responsibility. I agree with this order, the loose abuse of language triggers an avalanche.

Try not to hate on the most stigmatized and vulnerable population (BPD) just because it’s easy for you. They could well be triggered by alcohol, you know, because of tiny issues like domestic violence from drunk men, an abusive drunk stepfather raping them (40% of women with BPD were raped as children, a conservative estimate), past maladaptive coping with alcohol could be a bad memory for them. Countertransference isn’t an excuse. “People in crisis to hang their excuses on”. A crisis is a crisis. “immediate sympathy”. From who? You? Doesn’t seem like it. “A way out of future responsibility”, from what? A trauma response which they can’t control and need to be assisted with? It’s 2021.

The clinician’s response was totally unprofessional. You don’t talk about a patient or their accompanying relatives behind their back, like someone was rolling over last’s night’s football scores around the snack table or coffee machine with their co-workers. No offense meant, MOTIMT, but you should’ve said something, especially if this ‘clinician’ saw you as an equal.

If I had any idea that a health care worker I interacted with frequently thought that way about me or mine, I’d find another one. I realize that someone can’t just button up feelings they have, strong or not, being just as human as anybody else, but that is not the way to be talking about someone’s patients or behind their back.

“It’s like OMG: you start saying it as a joke but quickly find yourself using it for real.”

Yes, how you practice is how you play.