PART 2 OF THE CHARACTER DISCUSSION OF VARYS

The degree and kind of a man’s sexuality reach up into the ultimate pinnacle of his spirit.Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil

One fact we learn early on about Lord Varys, and are reminded of frequently, is that he is a eunuch. His castration is one of the central features of his character.

Looking across the series, we see other examples of eunuchs, most notably in the Meereenese warrior, Strong Belwas, and the slave soldiers from Astapor, known as the Unsullied.

All of these characters are extraordinary in some way. Varys is one of the wisest characters in the series, the Unsullied some of the finest warriors. This connection between castration and talent is suggestive. G.R.R. Martin seems to be hinting that sexual desire is an impediment to the development of other kinds of human excellence.

This is not to say that G.R.R. Martin teaches that we must all renounce sex or become castrated in order to flourish. There are other characters in the books, possessing considerable degrees and types of wisdom, like Melisandre, Tywin Lannister, and Grand Maester Pycelle, who do have their sexual parts very much intact. And there are certainly warriors of which the same can be said – the Kingslayer, Jaime Lannister, for example, whose skill with a sword is immense, but whose life is terribly complicated by his sexual and romantic relationship with his sister, and the lustful and fearsome Prince Oberyn Martell, the Red Viper, a fighter of tremendous skill and equally tremendous sexual appetite. All of these and more have their sex organs still with them, but the preponderance of the other type in the work is still unusual.

It is surely a better thing than castration or even celibacy to achieve some mastery over sexual desire – to be able to see it in its place, for what it is actually worth, such that one can pursue it as a good but also pursue higher things. Castration and celibacy arise out of a contempt for the body and for sex, they are not natural, and they signify neither a mastery of these things, nor a fitting appreciation of them.

This is not lost on G.R.R. Martin. As noted, it is not the case that all the best people in his saga are without their sexual organs. But he does seem very keen to feature characters that are without them too, and to explore the possibilities for them. After all, while castration might be a strong response to an inherent weakness, it surely makes matters less complicated for those people who achieve excellence in other regards. So many individuals in A Song of Ice and Fire attain greatness, only to be undone by love and sex.

Varys, of course, is not one of these. Though it must be noted that he did not choose to be castrated. As a young boy, an orphan, Varys was purchased by a man who removed his parts for use in a ritual of Blood Magic. And this wasn’t done to Varys for his own benefit, in any sense. For the army of Unsullied, by contrast, the castration serves to strip them further of their own personal identities and individual longings, to make them more cohesive as a fighting group, and more devoted to such glory as they can attain in battle. But just because it wasn’t done for Varys’ benefit doesn’t mean that he didn’t gain anything by it.

On the one hand, it makes Varys less in need of mastering sexual desire. On the other hand, it gives him even greater obstacles to rise above. Most people who are castrated as children won’t go the way of Varys. It is a serious and crippling harm that has been done to them, with innumerable physical and psychological consequences. It is a violence that can destroy most human beings. In that sense, Varys has had to work even harder to get to the top.

It has also changed how Varys pursues power. He is often described as womanish or effeminate, both in his manner and appearance, as well as in the mode through which he pursues power. He is a master of whisperers, a purveyor of secrets and damaging gossip, the master of a large network of spies, his “little birds”. He works behind the scenes and through manipulation, rather than through the ostensibly manly modes of battle or open challenges for power.

As has already been established, however, power is very much on Varys’ mind. One is tempted to say that his sexuality, his status as a eunuch, has become an asset for Varys in his pursuit of power. He does not seem to mind the jokes and jeers that so many other characters in the book make at his expense. He even seems to relish the extent to which it makes him seem less to them, and thereby incline them to underestimate him at their own peril. He appears to have learnt that sexuality can be mastered as anything else, guise or disguise, manner of lion or manner of fox, in order to achieve one’s ends.

Read PART 1 OF THE CHARACTER DISCUSSION OF VARYS

RETURN TO THE MAIN HUB FOR DISCUSSION OF THE POLITICS OF A SONG OF ICE AND FIRE HERE.

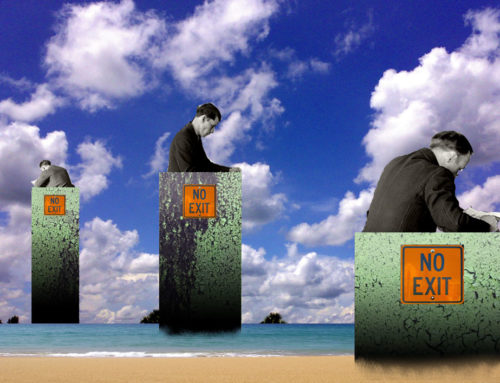

(Image: Spiders Web by Camon90, distributed under a CC BY-SA 3.0 licence. Via DeviantArt.)

I’m enjoying both the format (looking at each aspect of Varys’ character through one passage from one philosopher) as well as the content itself. But I’m wondering about what Machiavelli would make of Varys’ castration, and I’d like to hear a bit more than what is said in the final paragraph.

In particular:

“On the one hand, it makes Varys less in need of mastering sexual desire. On the other hand, it gives him even greater obstacles to rise above. Most people who are castrated as children won’t go the way of Varys. It is a serious and crippling harm that has been done to them, with innumerable physical and psychological consequences. It is a violence that can destroy most human beings. In that sense, Varys has had to work even harder to get to the top.”

What kind of prince is Varys? A new one, surely, and one who has risen and maintains his power by his own arms. But as the author notes in the closing paragraph, his castration is a kind of asset to Varys. And perhaps this is what the author was thinking in this piece—in Machiavelli’s economy of virtu, adversities are in the long run goods for certain human types, precisely because they give him the opportunity to rise above them. Is Varys’ castration the gift of fortune, as the enslavement of Israel was the gift of fortune to Moses or the fragmentation of the Athenians the gift of fortune to Theseus?

[I have assumed we should refer to Varys as a prince, but perhaps the relation and distinction between prince and counselor should be discussed.]

More broadly: part of Machiavelli’s training of the prince involves his de-eroticization. This begins even in the Epistle Dedicatory, where Machiavelli denigrates and departs from the usual praise of beautiful objects and proffers instead something useful. Waller Newell’s “Tyranny” expands upon this theme greatly—eros, ontology, and their relation to tyranny—in discussing Machiavelli and his ancient predecessors. I think his analysis there fits quite well with Varys’ apparently devotion to the Realm; the unerotic tyrant is less distracted by the pitfalls of, say, the tyrant of Republic 8.

Finally, it would be interesting to compare Varys’ lack of eros with Baelish’s. Baelish might present an even more impressive case of the ambitious mastery of eros: he is still equipped to gratify it; he is surrounded with opportunities to do so, but (as far as we can tell, or I can remember) doesn’t; and despite initial appearances with respect to Catelyn and Sansa, he is not even distracted by a higher eros that is drawn to beauty and those who are worthy of love, and even seems able to deploy it when it suits him. But that would require another conversation.

Leonidas – I did indeed mean to suggest that Varys’s castration might be understood as a gift of fortune, in the Machiavellian sense.

I am not sure that Varys can be understood as a new prince – he is not a founder, after all, or at least not so far. Perhaps if he succeeds in reestablishing the Targaryens (if that is in fact his design) as rulers of Westeros, he will somehow also re-found or modify the regime in such a way that he might be considered a new prince. If you think I’m wrong about this, please explain.

I am also not convinced that the distinction between prince and counselor is ultimately a very fine one in Machiavelli’s work. A prince is the effectual ruler, if I understand Machiavelli correctly, and whether he is a prince in name or a counselor in name or even an author of books, what matters is the effectual truth – the names and titles are of far less concern. Again, if you think I’m wrong about this or you had something else in mind, please let me know.

Your suggestion that there be a sustained comparison between Varys and Baelish, especially regarding their lack of eros, is a terrific one. I will certainly think about it more, but by all means let me know if you would be interested in developing the idea further here yourself.